A participant from Convening The Center recently emailed and asked what technology we had used for some of our interactive components within the phase 2 and 3 gatherings for the project. The short answer was “Google Slides” but there was a lot more that went into the choice of tech and the design of activities, so I ended up writing this blog post in case it was helpful to anyone else looking for ideas for interactive activities, new icebreakers for the digital era, etc.

Design context:

We held four small (8 people max) gatherings during “Phase 2” of CTC and one large (25 participants) gathering for “Phase 3”, and used Zoom as our videoconference platform of choice. But throughout the project, we knew we were bringing together random strangers to a meeting with no agenda (more about the project here, for background), and wanted to have ways to help people introduce themselves without relying on rote introductions that often fall back to name, title/organization (which often did not exist in this context!), or similar credentials.

We also had a few activities during the meeting where we wanted people to interact, and so the “icebreakers” (so to speak) were a low-stress way to introduce people to the types of activities we’d repeat later in the meeting.

Technology choice:

I’ve seen people use Jamboard (made by Google) for this purpose (icebreakers or introductory activities), and it was one that came to mind. However, I’ve been a participant on a Jamboard for a different type of meeting, and there are a few problems with it. There’s a limit to the number of participants; it requires participants to create the item they want to put on the board (e.g. figure out how to add a sticky note), and the examples I’ve seen content-wise ended up using it in a very binary way. That in some cases was due to the people designing the activity (more on content design, below), but given that we wanted to also use Google Slides to display information to participants and also enable notetaking in the same location, it also became easy to replicate the basic functionality in Google Slides instead. (PS – this article was helpful for comparing pros/cons of Jamboard and Google Slides.)

Content choices:

The “icebreakers” we chose served a few purposes. One, as mentioned above, was familiarizing people with the platform so we could use it for meeting-related activities. The other was the point of traditional icebreakers, which is to help everyone feel comfortable and also enable people to introduce themselves. That being said, most of the time introductions rely on credentials, and this was specifically a credential-less or non-credential-focused gathering, so we brainstormed quite a bit to think of what type of activities would allow people to get comfortable interacting with Google Slides and also introduce themselves in non-stressful ways.

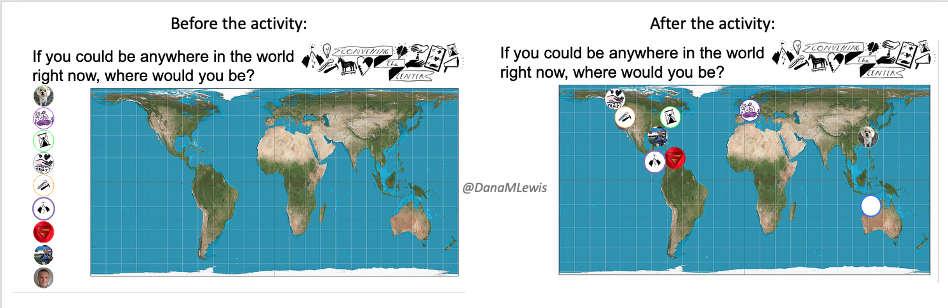

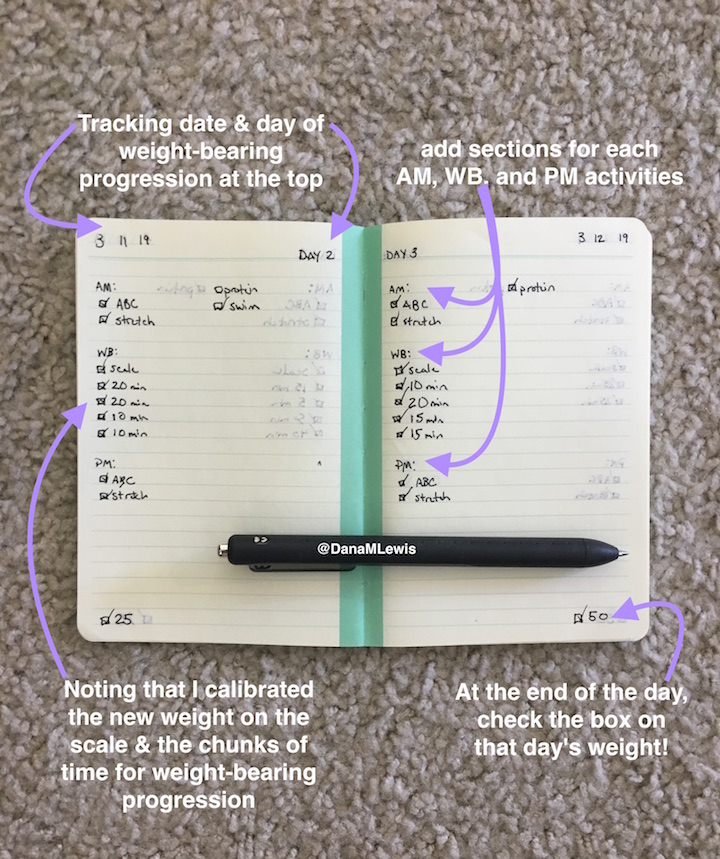

The first activity we did for the small groups was a world map image and asked people to drag and drop their image to “if you could be anywhere in the world right now, where would you be?”. (I had asked all participants to send some kind of image in advance, and if they didn’t, supplied an image and told them what it was during the meeting.) I had the images lined up to the side of the map, and in this screenshot you can see the before and after from one of the groups where they dragged and dropped their images.

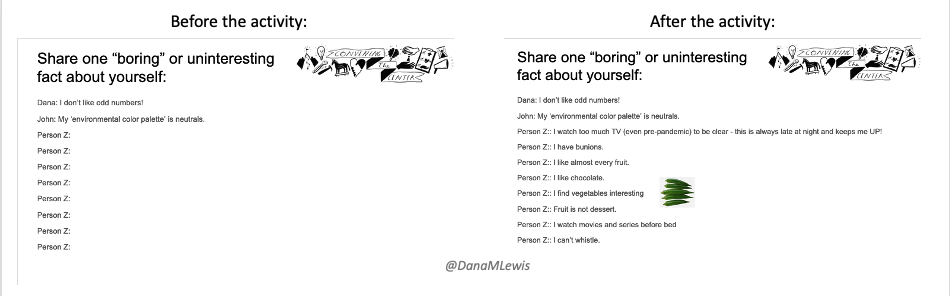

The second activity was a slide where we asked everyone to type “one boring or uninteresting fact about themselves”. Again, this was a push back against traditional activities of “introduce yourself by credentials/past work” that feels performative and competitive. I had everyone’s names listed on the slide, so each could type in their fact. It ended up being a really fun discussion and we got to see people’s personalities early on! In some cases, we had people drop in images (see screenshot of example) when there was cross-cultural confusion about the name of something, such as the name of a vegetable that varies worldwide! (In this case, it was okra!)

We also did the same type of “type in” activity for “Ask me about my expertise in..” and asked people to share an expertise they have personally, or professionally. This is the closest we got to ‘traditional’ introductions but instead of being about titles and organizations it was about expertise in activities.

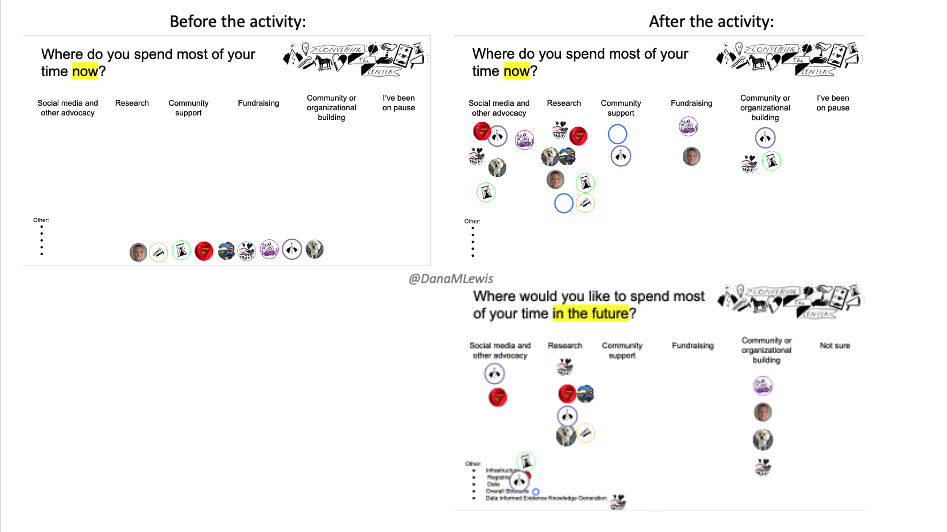

Finally, we did the activity most related to our meeting that I had wanted people to be comfortable with dragging and dropping their image for. We had a slide, again with everyone’s image present, and a variety of types of activities listed. We queried participants about “where do you spend most of your time now?”. Participants dragged and dropped their images accordingly. In some cases, they duplicated their image (right click, duplicate in Google Slides) to put themselves in multiple categories. We also had an “other” category listed where people could add additional core activities.

Then, we had another slide asking where do they want to spend most of their time in the future? The point of this was to be able to switch back and forth between each slide and visualize the changes for group members – and also so they could see what types of activities their fellow participants might have experience in.

Some of these activities are similar to what you might do in person at meetings by “dot voting” on topics. This type of slide is a way to achieve the same type of interactivity digitally.

Facilitating or moderating these types of interactive activities

In addition to choosing and designing these activities, I also feel that moderating or facilitating these activities played a big role in the success of them for this project.

As I had mentioned in the technology choice section, I’ve previously been a participant in other meeting-driven activities (using Jamboard or other tech) where the questions/activities were binary and unrelated to the meeting. Questions such as “are you a dog or cat person? Pick one.” or “Is a hot dog a sandwich?” are binary, and in some cases a meeting facilitator may fall into the trap of then ascribing characteristics to participants based on their response. In a meeting where you’re trying to use these activities to create a comfortable environment for participation amongst virtual strangers…that can backfire and actually cause people to shut down and limit participation in the meeting following those introductory activities.

As a result of having been on the receiving end of that experience, I really wanted to design activities with relevance to our meeting (both in terms of technology used and the content) as well as enough flexibility to support whatever level of involvement people wanted to do. That included being prepared to move people’s images or type in for them, especially if they were on the road and not able to sit stationary and use google slides. (We had recommended people be stationary for this meeting, but knew it wasn’t always possible, and were prepared to still help them verbally direct us to move their image, type in their fact, etc. This also can be very important for people with vision impairment as well, so be prepared to assist people in completing the activities for whatever reason, and also to verbally describe what is going on the slides/boards as people move things or type in their facts. This can aid those with vision impairment and also those who are on the go and can’t look at a screen during the meeting for whatever reason.)

One other reason we used Google Slides is so we’d end up with a slide for each breakout group to be able to take notes, and a “parking lot” slide at the end of the deck for people to add questions or comments they wanted to bring back up in the main group or moving forward in future discussions. Because people already had the Google Slide deck open for the activity, it was easy for them to scroll down and be in the notetaking slide for their breakout group (we colored the background of the slides, and told people they were in the purple, blue, green, etc. slides to make it easier to jump into the right slide).

One other note regarding facilitation with Zoom + Google Slides is that the chat feature in Zoom doesn’t show previous chat to people who join the Zoom meeting after that message is sent. So if you want to use Zoom chat to share the Google Slides link, have your link saved elsewhere and assign someone to copy and paste that message into the chat frequently, so all participants have access and can open the URL as they join the meeting. (This also includes if someone leaves and re-enters the meeting: you may need to re-post the link yet again into chat.)

—

TLDR, we used Google Slides to facilitate meeting note taking, digital “dot voting” and other interactive icebreaker activities alongside Zoom.

Recent Comments