I’ve been thinking a lot about stigma, per a previous post of mine, and how I generally react to, learn about, and figure out how to deal with new chronic diseases.

I’ve observed a pattern in my experiences. When I suspect an issue, I begin with research. I read medical literature to find out the basics of what is known. I read a high volume of material, over a range of years, to see what is known and the general “ground truth” about what has stayed consistent over the years and where things might have changed. This is true for looking into causal mechanisms as well as diagnosis and then more importantly to me, management/treatment.

A lot of times with autoimmune related diseases…the causal mechanism is unknown. There are correlations, there are known risk factors, but there’s not always a clear answer of why things happen.

I realize that I am lucky that my first “thing” (type 1 diabetes) was known to be an autoimmune condition, and that probably has framed my response to celiac disease (6 years later); exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (19+ years after diabetes); and now Graves’ disease (19+ years after diabetes). Why do I think that is lucky? Because when I’m diagnosed with an autoimmune condition, it’s not a surprise that it IS an autoimmune condition. When you have a nicely overactive immune system, it interferes with how your body is managing things. In type 1 diabetes, it eventually makes it so the beta cells in your pancreas no longer produce insulin. In celiac, it makes it so the body has an immune reaction to gluten, and the villi in your small intestine freak out at the microscopic, crumb-level presence of gluten (and if you keep eating gluten, can cause all sorts of damage). In exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, there is possibly either atrophy as a result of the pancreas not producing insulin or other immune-related responses – or similar theories related to EPI and celiac in terms of immune responses. It’s not clear ‘why’ or which mechanism (celiac, T1D, or autoimmune in general) caused my EPI, and not knowing that doesn’t bother me, because it’s clearly linked to autoimmune shenanigans. Now with Graves’ disease, I also know that low TSH and increased thyroid antibodies are causing subclinical hyperthyroidism symptoms (such as occasional minor tremor, increased resting HR, among others) and Graves’ ophthalmology symptoms as a result of the thyroid antibodies. The low TSH and increased thyroid antibodies are a result of my immune system deciding to poke at my thyroid.

All this to say…I typically wonder less about “why” I have gotten these things, in part because the “why” doesn’t change “what” to do; I simply keep gathering new data points that I have an overactive immune system that gives me autoimmune stuff to deal with.

I have contrasted this with a lot of posts I observe in some of the online EPI groups I am a part of. Many people get diagnosed with EPI as a result of ongoing GI issues, which may or may not be related to other conditions (like IBS, which is often a catch-all for GI issues). But there’s a lot of posts wondering “why” they’ve gotten it, seemingly out of the blue.

When I do my initial research/learning on a new autoimmune thing, as I mentioned I do look for causal mechanisms to see what is known or not known. But that’s primarily, I think, to rule out if there’s anything else “new” going on in my body that this mechanism would inform me about. But 3/3 times (following type 1 diabetes, where I first learned about autoimmune conditions), it’s primarily confirmed that I have autoimmune things due to a kick-ass overactive immune system.

What I’ve realized that I often focus on, and most others do not, is what comes AFTER diagnosis. It’s the management (or treatment) of, and living with, these conditions that I want to know more about.

And sadly, especially in the latest two experiences (exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and Graves’ disease), there is not enough known about management and optimization of dealing with these conditions.

I’ve previously documented and written quite a bit (see a summary of all my posts here) about EPI, including my frustrations about “titrating” or getting the dose right for the enzymes I need to take every single time I eat something. This is part of the “management” gap I find in research and medical knowledge. It seems like clinicians and researchers spend a lot of time on the “why” and the diagnosis/starting point of telling someone they have a condition. But there is way less research about “how” to live and optimally manage these things.

My fellow patients (people with lived experiences) are probably saying “yeah, duh, and that’s the power of social media and patient advocacy groups to share knowledge”. I agree. I say that a lot, too. But one of the reasons these online social media groups are so powerful in sharing knowledge is because of the black hole or vacuum or utter absence of research in this space.

And it’s frustrating! Social media can be super powerful because you can learn about many n=1 experiences. If you’re like me, you analyze the patterns to see what might be reproducible and what is worth experimenting in my own n=1. But often, this knowledge stays in the real world. It is not routinely funded, studied, operationalized, and translated in systematic ways back to healthcare providers. When patients are diagnosed, they’re often told the “what” and occasionally the “why” (if it exists), but left to sometimes fall through the cracks in the “how” of optimally managing the new condition.

(I know, I know. I’m working on that, in diabetes and EPI, and I know dozens of friends, both people with lived experiences and researchers who ARE working on this, from diabetes to brain tumors to Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s and beyond. And while we are moving the needles here, and making a difference, I’m wanting to highlight the bigger issue to those who haven’t previously been exposed to the issues that cause the gaps we are trying to fill!)

In my newest case of Graves’ disease, it presented with subclinical hyperthyroidism. As I wrote here, that for me means the lower TSH and higher thyroid antibodies but in range T3 and T4. In discussion with my physician, we decided to try an antithyroid drug, to try to lower the antibody levels, because the antibody levels are what cause the related eye symptoms (and they’re quite bothersome). The other primary symptom I have is higher resting HR, which is also really annoying, so I’m also hoping it helps with that, too. But the game plan was to start taking this medication every day; and get follow-up labs in about 2 months, because it takes ~6 weeks to see the change in thyroid levels.

Let me tell you, that’s a long time. I get that the medication works not on stored thyroid levels; thus, it impacts the new production only, and that’s why it takes 6 weeks to see it in the labs because that’s how long it takes to cycle through the stored thyroid stuff in your body.

My hope was that within 2-3 weeks I would see a change in my resting HR levels. I wasn’t sure what else to expect, and whether I’d see any other changes.

But I did.

It was in the course of DAYS, not weeks. It was really surprising! I immediately started to see a change in my resting HR (across two different wearable devices; a ring and a watch). Within a week, my phone’s health flagged it as a “trend”, too, and pinpointed the day (which it didn’t know) that I had started the new medication based on the change in the trending HR values.

Additionally, some of my eye symptoms went away. Prior to commencing the new medication, I would wake up and my eyes would hurt. Lubricating them (with eye drops throughout the day and gel before bed) helped some, but didn’t really fix the problem. I also had pretty significant red, patchy spots around the outside corner of one of my eyes, and eyelid swelling that would push on my eyeball. 4 days into the new medication, I had my first morning where I woke up without my eyes hurting. The next day it returned, and then I had two days without eye pain. Then I had 3-4 days with the painful eyes. Then….now I’m going on 2 weeks without the eye pain?! Meanwhile, I’m also tracking the eye swelling. It went down to match the eye pain going away. But it comes back periodically. Recently, I commented to Scott that I was starting to observe the pattern that the red/patchy skin at the corner and under my right eye would appear; then the next day the swelling of and above the eyelid would return. After 1-2 days of swelling, it would disappear. Because I’ve been tracking various symptoms, I looked at my data the other day and saw that it’s almost a 6-7 day pattern.

Interesting!

Again, the eye stuff is a result of antibody levels. So now I am curious about the production of antibodies and their timeline, and how that differs from TSH and thyroid hormones, and how they’re impacted with this drug.

None of that is information that is easy to get, so I’m deep in the medical literature trying again to find out what is known, whether this type of pattern is known; if it’s common; or if this level of data, like my within-days impact to resting HR change is new information.

Most of the research, sadly, seems to be on pre-diagnosis or what happens if you diagnose someone but not give them medication in hyperthyroid. For example, I found this systematic review on HRV and hyperthyroid and got excited, expecting to learn things that I could use, but found they explicitly removed the 3 studies that involved treating hyperthyroidism and are only studying what happens when you don’t treat it.

Sigh.

This is the type of gap that is so frustrating, as a patient or person who’s living with this. It’s the gap I see in EPI, where little is known on optimal titration and people don’t get prescribed enough enzymes and aren’t taught how to match their dosing to what they are eating, the way we are taught in diabetes to match our insulin dosing to what we’re eating.

And it matters! I’m working on writing up data from a community survey of people with EPI, many of whom shared that they don’t feel like they have their enzyme dosing well matched to what they are eating, in some cases 5+ years after their diagnosis. That’s appalling, to me. Many people with EPI and other conditions like this fall through the cracks with their doctors because there’s no plan or discussion on what managing optimally looks like; what to change if it’s not optimal for a person; and what to do or who to talk to if they need help managing.

Thankfully in diabetes, most people are supported and taught that it’s not “just” a shot of insulin, but there are more variables that need tracking and managing in order to optimize wellbeing and glucose levels when living with diabetes. But it took decades to get there in diabetes, I think.

What would it be like if more chronic diseases, like EPI and Graves’ disease (or any other hyper/hypothyroid-related diseases), also had this type of understanding across the majority of healthcare providers who treated and supported managing these conditions?

How much better would and could people feel? How much more energy would they have to live their lives, work, play with their families and friends? How much more would they thrive, instead of just surviving?

That’s what I wonder.

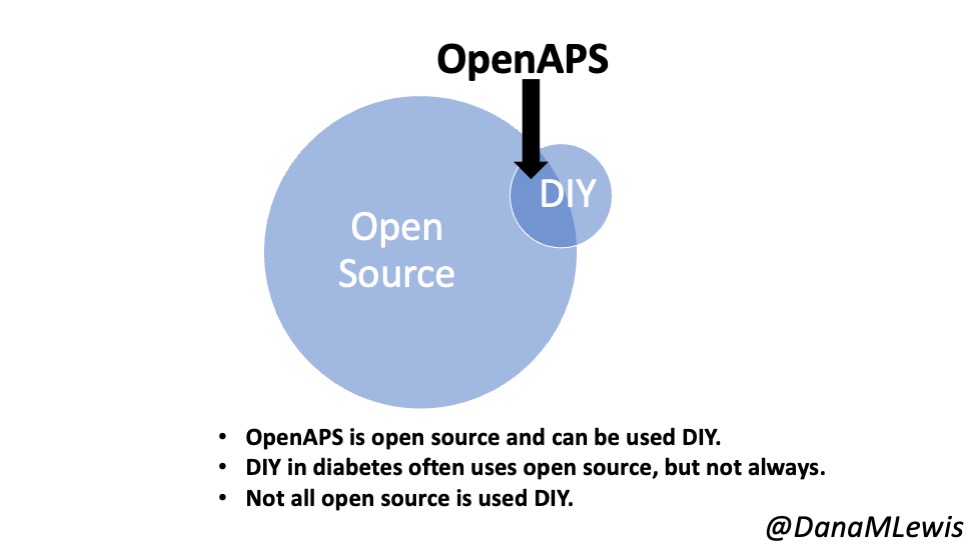

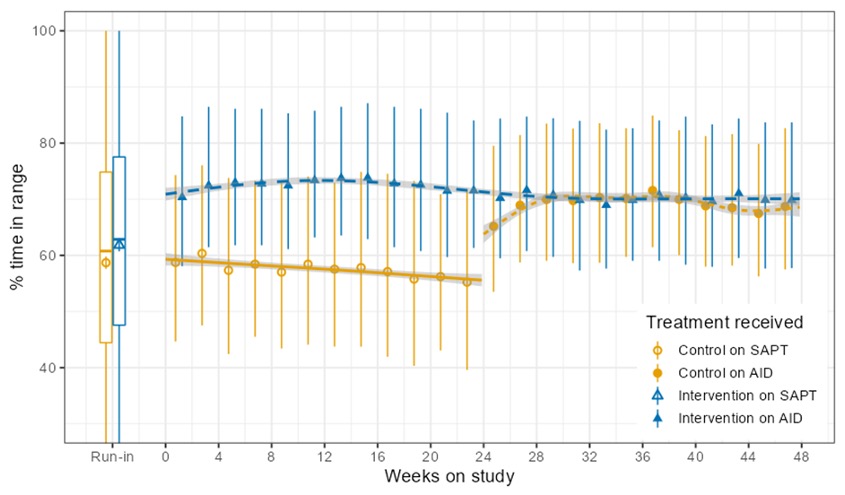

I’m thrilled to share that the results of the first RCT on open source automated insulin delivery (AID) is now published in a peer-reviewed medical journal (New England Journal of Medicine, known as NEJM). You can find it at NEJM

I’m thrilled to share that the results of the first RCT on open source automated insulin delivery (AID) is now published in a peer-reviewed medical journal (New England Journal of Medicine, known as NEJM). You can find it at NEJM

Recent Comments