The canary in the coal mine was my swollen eyelids. No one (including my providers) seemed to care over the last 3 or so years, but all along, I knew it was a matter of time before my body decided to speak up even more loudly and tell me what else was wrong and what was causing the swollen eyelids. And in January, it was time. My body decided to speak up, and it did so loudly.

I woke up one day in January with a sensation of wool wrapped around my lungs. I could breathe…but not normally. It felt like oxygen was not flowing effectively out of my lungs. My VO2max also dropped suddenly and unexpectedly (given my activity levels) by about a point. And sometimes when I would exercise, my SpO2 levels would drop well below where they were supposed to be, and take a while to come up. Some days were better, but some days I could not walk and talk on the phone at the same time without feeling like I needed to gasp for breath in between sentences (and much shorter sentences than I would normally say). My lungs, in other words, have problems.

I’ve spent the last ~3 months trying to figure out what’s wrong with my lungs, but we are still not to the point where we can define exactly what is wrong. Or, how to make them better. Yet, at least. (I’m pessimistic about “fixing them” but I’d sure like to stop them from getting ‘worse’). Right now, they’re not TOO bad. I did pulmonary function testing and some of my numbers are in ‘normal’ range (although they’ve dropped anywhere from 5-17% from baseline in 2015, when I had a bunch of above-normal results). Other numbers, however, are very below normal (<80% is not normal): some are in the 65-70% range. Bleh. Some are even lower. Collectively, they show TWO possible types of things going on, one of which is restrictive lung disease of some sort; the other is some possible small airways-related disease (which means albuterol might help that). No obstruction, which is good, in part because it crosses off one area of concern off the list, but I still have two other areas of concern. I also did a follow up high-resolution CT (aka HRCT) on my lungs which showed no obvious inflammation or fibrosis (scarring) which is both really good news – nothing terribly wrong yet to the naked eye – but also frustrating because clearly there is something wrong. My doctor and I are both concerned by the level of symptoms, and my doctor managing my autoimmune condition has suggested that the lung stuff, whatever it is, is now a separate disease/on a separate path than the rest of my autoimmune disease activity, and it should be managed by a pulmonologist.

So we are still waiting until my pulmonologist appointment to get more answers (every specialist referral means another 6 weeks to schedule the next new appointment, stringing out the problem solving process over time), and in the meantime I try to do what exercise I can do. Which is still exercising every day, but slowly and with lungs that hurt. Some days with lower blood oxygen availability; some days with OK oxygen (as measured by SpO2). Some days also hurt more to physically breathe, and on those days that often starts from the moment I wake up before I’ve even sat up in the bed. I have not been running a lot, which makes me sad. When I do run, it’s not joyful most of the time, although I try to appreciate the ability to run at all on those ‘bad’ days and savor the few moments of joy on the few better days. Not because of my legs, but because of my lungs. Sometimes just walking, even super slowly, also sucks. But sometimes, I can still ski or hike like I used to, and other days I ski or hike like a snail pushing its way through a sea of peanut butter (very slowly and usually with a lot of vocal complaining about it, when I can afford to catch and waste my breath on words to complain). I’ve had to shift my focus from training with a schedule and a plan to trying to figure out a list of what I can do on a “good lung day” (which is <50% of the time). On “bad lung” days, I just focus on moving at all, however seems feasible that day.

Meanwhile, it’s not just my lungs. At the same time the lung stuff developed, I also developed pretty serious and sudden joint pain. It particularly affects the vertebrae in my spine, hips, and upper spine between my shoulders and neck. Did you know you have ‘joints’ where your ribs connect to cartilage and your cartilage connects to your sternum? I’m re-learning some of the many places we have joints that we usually don’t pay much attention to. Heat helps, so I spend a lot of time sitting against a heating pad, which thankfully means the biggest areas impacted by this issue can get regular heat therapy. But it also will sporadically “pang” with pain in other random joints such as in my hand, the middle of my foot, a toe joint, or my shoulder. Oral NSAID does nothing for the pain, but when the pain is in easy-to-reach spots, topical NSAID gel does help some, as does the application of heat to those areas. It can get pretty problematic, though, to the point where rolling over in bed at night wakes me up taking my breath away because I rolled over and the joint pain in my spine was so painful it woke me up. (And thus I don’t sleep well those nights, which also stinks.)

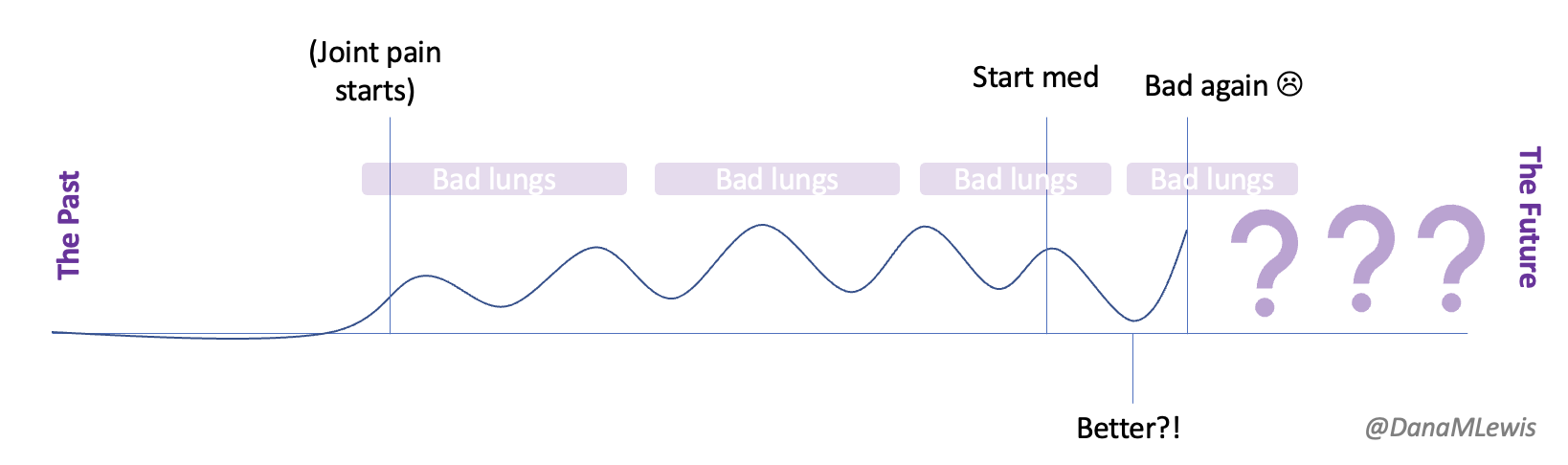

What the joint pain, like the eyelids cycling in and out of inflammation, is telling us is: the inflammation is spreading in other parts of my body and my body is attacking itself elsewhere, too. My eyelids continue to swell, but now there’s also a red patch particularly outside of my right eye that provides a visual cue to Scott when my inflammation is particularly at peak. But the joint pain and the lungs collectively mean my fifth autoimmune disease is angry and kicking in protest, lashing out at the rest of my body. And we need to do something about that, and so we are.

Treating autoimmune diseases is not without risk due to the treatment itself. There’s the short-term risk of side effects and the long-term risk of side-effects. When autoimmune disease gets as problematic as mine is (attacking my lungs; the escalating joint pain); it warrants risking the side effects of the medication, even though it’s scary. Also scary is the knowledge that we are trying to tweak my immune system. Even though I know my immune system is *too* strong and *overreacting*, it’s what I know, and it’s scary to think about trying to turn it down, because there is the risk that it overshoots and turns down too far in the process of trying to take it down just a notch.

Ultimately, the first-line treatment my doctor and I chose is a mild version of immunosuppression, which is an immunomodulator designed to modulate only part of the immune system. This is more mild than what most people think of when they think of immunosuppression (e.g. to go with organ transplant), and while they don’t know exactly how it works, it seems like it causes an effect of turning down *part* of the immune system, but not all. (In theory.) While it’s not been very well tested in studies in my autoimmune disease (this is the story line through allllll the medical literature about my condition), there’s a “cousin” autoimmune disease for which there are a lot of studies and data showing it helps some people, and particularly has a good chance of helping the joint pain. However, the risk of negative outcomes is also not zero. In the medicine we decided was best for me, there is a risk of it accumulating in my retina and causing vision loss. Yikes. The risk in the first 5 years is about 1%, meaning that in people who take this medication every day for 5 years, 1 in 100 will begin to have vision issues. At the 10 year mark, however, this goes up, and 10% (10 in 100 people) begin to have vision issues. And the problem is, this vision damage is not reversible. Plus, the medication has a half life of months, meaning it takes time to ramp up, but also that if you start to notice problems and need to stop the medication, there is another set of weeks to months before the medication levels actually begin reducing in your body, so you get additional damage possibly during that time. As one might imagine, I am very nervous about this risk profile, but this possibly helps illustrate exactly how bad the situation is that I am in: this joint pain is not ideal for quality of life and it is a serious symptom of a serious problem, which is a rampaging immune system that needs to be treated.

While I am not currently fully immunosuppressed, it does mean that I am choosing to continue to be careful to limit my risk in exposure to infectious diseases. For me, that means continuing what I’ve been doing since early on in the pandemic: I am already using a portfolio of risk mitigation strategies including seeking better ventilated air in indoor spaces (using CO2 monitor); masking in any indoor spaces outside home (unless I am at family’s house where everyone confirms no symptoms, tests negative, etc); using portable air purifiers and far-UVC lights when feasible; getting vaccinated and boosted against all the infectious diseases I can, etc. That feels right for me, although it’s not necessarily what others might choose to do in my situation. But again, my risk profile not only includes 5 autoimmune diseases, for which we are trying to turn my immune system *down*; I also have some kind of lung disease now, with lowered lung capacity that is directly influencing my daily living ability. So I am happy to do all the easy things that I can to further lower the risk of hurting my lungs more, such as by limiting exposure to acute respiratory infections that could lead to all kinds of further issues and complications that I just don’t need or want to deal with. So, the biggest change is mostly to what I will continue to ask of family members, which is reporting any and all symptoms of any type of illness, even if it’s “just” a cold, because a “cold” to someone else is likely going to be a lot more serious to me, given my immune and lung status. Plus, too, I may end up needing to switch to a different level of immunosuppression, which further changes the calculation of short- and long-term risk of acute illness exposure.

I started the medicine a few weeks ago, and I managed to avoid the worst of the short-term side effects that cause people to discontinue it. In weeks 2 & 3, it seemed like it was helping reduce the joint pain. I got excited, but then very un-excited when the joint pain manifested again (along with re-swollen eyelids and the spreading red patch outside of my eye). I was hoping this medication would permanently depress the inflammation and systemic attacks, but instead, so far, it looks like it might slightly dampen the inflammation cycles (and thus symptoms), and they haven’t yet completely gone away. And my lungs continue to be problematic, which matches my doctor’s prediction so far that they will not be impacted by this medication and I need some ideas from the pulmonologist to treat my lungs.

So here I am. 5 (or 6) autoimmune diseases; still acutely aware of the stigma that comes with living with (so) many chronic diseases; entering new territory of immunomodulation; and possibly in the future, maybe needing more immunosuppression. I don’t have a lot of answers or even a good understanding of what is going on with my body (for example, what exactly the problem(s) are in my lungs), which is frustrating. More acutely, some days just stink either due to bad lungs or due to joint pain. When I get really unlucky, I have a bad joint day on the same day as a bad lung day. The challenge with bad lung days is that it impacts my ability to exercise, whereas my joint pain doesn’t keep me from exercising (because it’s no worse during exercise and sometimes exercise distracts my brain from the pain signals). So during bad lung days, some of my “treatment” options for the bad joint pain are reduced. Bad lung days also make me feel really fatigued and short of breath even sitting down doing nothing, so I have some days where I’m doing normal workloads of things I want to do, and other days where I’m doing less than I would like. I have been slow to respond to emails related to non-time-sensitive-projects because basically, I’m over here just trying to breathe, and that’s hard. So: sorry to anyone who’s read this who has happened to email me – consider this an auto-responder about why I have not yet responded.

Stay tuned for more posts: I’ll be using this framework to talk about exercise strategies for exercising with ‘bad lungs’ and strategies that I’ve found to be effective (see this post as an example for strategies) so far on the days where I’m struggling to breathe and exist but also want to exercise so I don’t decondition my body so I can do the things I want to do on the “good days”.

—

If you’re a family member or friend who’s read this and wants to acknowledge what I’m going through but doesn’t know what to say – it’s ok. I don’t know what to say, either, which is in part why I haven’t said anything to most people! But it felt like it was time to start sharing some of what I’ve been going through. Feel free to send me a purple heart emoji (or a cat picture), no caption/text needed, and that’s an a-ok way to acknowledge that you’ve seen this. 💜

—

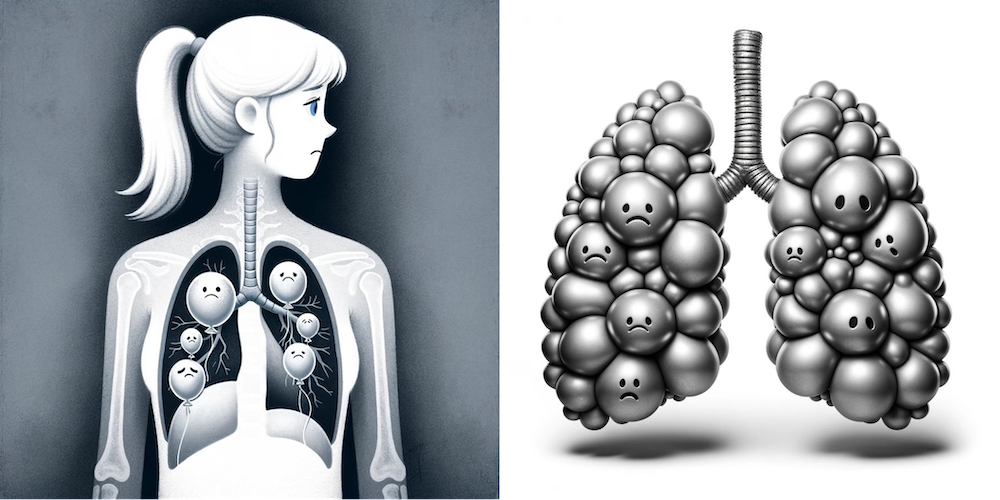

PS – one of my friends described my lungs as “sad balloons” and for some reason, that analogy felt really appropriate to how they physically feel inside my rib cage. Sad, and ineffective. I gave ChatGPT some prompts to illustrate “sad balloon” lungs and ended up with these, which feels cathartic to illustrate.

Recent Comments