As part of my pandemic “fun” (but fortunately not from COVID-19 infection, which I’ve avoided), I developed some gastrointestinal dysbiosis. Gastrointestinal dysbiosis generally means microbiome dysfunction of some kind, hypothetically caused by a loss of ‘good’ bacteria and getting out of balance with ‘bad’ bacteria. I don’t have a diagnosable disease such as IBS (that and many other things were ruled out through a variety of medical testing), but I definitely have some dysfunction going on causing varying levels of GI symptoms now for almost a year and a half. At their worst, I was waking up overnight suddenly with sharp abdominal pain out of the blue – scary! At their least annoying, it was excess gas and general abdominal discomfort after eating. It ebbed and flowed and did not seem to be traceable to any particular cause. After several months, I consulted a gastroenterologist and did an assortment of tests over the course of ~10 months, slowed down by the pandemic and my reluctance to do in-person clinical tests until I was fully vaccinated against COVID-19 (we checked for c-diff and inflammation among other blood tests, did a CT scan, and eventually did a colonoscopy and endoscopy). The test results all came back normal. Eventually, we decided on a treatment plan that involved an antibiotic to kill excess bacteria in my small intestines. That worked – for about two weeks – and then my symptoms returned. I needed another solution, and before I went back to my gastroenterologist to talk about more extreme options, I decided first to self-test a low FODMAP diet.

(As a note to those who don’t know – I have had type 1 diabetes for almost 19 years, and celiac disease for about 13 years. As a result, I’ve been 100% fastidiously gluten free for 13 years and already eating a gluten free diet. P.S. I’m not a doctor and nothing in this post or this blog is medical advice.)

What a low FODMAP diet means in simplified terms

FODMAP is an acronym for different groups of short-chain carbohydrates, or sugars, that can cause symptoms for some people when they eat them, because the small intestine absorbs them poorly. FODMAP stands for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols.

The FODMAP diet is often discussed in the context of IBS (one particular condition), but it can be used by people with a variety of gut dysbiosis issues, many of whom (like me) don’t necessarily have a diagnosable condition or disease.

One reason I decided to try a low FODMAP diet is because I had identified onion and garlic as potential food-related triggers or variables that correlated with some of the worst of my symptoms. I began attempting to eliminate onion and garlic (and then onion powder and garlic powder) from my diet from January 2021-May 2021. It helped, but I was still having varying levels of symptoms.

Generally, people who describe being on a low FODMAP diet are referring to the first step of a three-step or three-phase diet. The first step is eliminating the major sources of FODMAPs. Then, a careful re-introduction process takes place to “test” and see which of the groups of FODMAPs you react to, and in what amounts. With that knowledge, the third phase is then eating what you’re willing to eat based on your knowledge of what FODMAPs bother you and what you’re willing to tolerate symptom-wise.

What most people don’t realize at first is that the amount of FODMAP and type of FODMAP matter, in each of the phases.

For example, there are a lot of blog posts and lists that will describe things that are “low FODMAP”. And they are partially right, but they leave out specifications that if you eat too many of them, the FODMAP amount may be considered “high” (meaning likely to trigger symptoms). Additionally, you can eat multiple things with the same type of FODMAP and cause FODMAP stacking, meaning you cumulatively have too much of the group of FODMAP and can cause symptoms, even if you ate the “right” low FODMAP portion of each individual food. Sometimes eating the same group within a short period of time can cause stacking, and so spreading them out 3-4 hours apart (or longer) could help reduce the effect.

(P.S. If you are looking for a simplified explanation to share with family and friends, skip to the bottom of the post!)

Resources for getting started with low FODMAP diet and some pros and cons to each

There are many blogs out there that will describe FODMAPs and the process of FODMAP elimination pretty well. Many have short lists of examples of foods that are “high FODMAP” and to avoid. The challenge, as I mentioned, is that the amount of food matters and knowing the type of FODMAP it contains really helps. There are many “high FODMAP” foods that you can eat in small quantities, and it’s also possible that you can eat large quantities of “low FODMAP” foods and accidentally stack FODMAPS from the same group and cause symptoms. With this diet and process, knowledge is power (even though it is very annoying to have to read ingredient labels and super sleuth everything you eat…).

There are several lists or spreadsheets of low FODMAP foods. Here is one that I found that is freely available. It lists the ingredient, it’s “max use”, and has information about the FODMAP group. This is information pulled from the Monash app and may be out of date – same with many blog posts or online lists you might find, such as this one!

How I used many of these free lists and blog posts was to get a sense of “green” or “low FODMAP” foods. There are a few types of foods that are really “free” meaning you can eat as much as you want because they don’t contain any level of FODMAP, so they shouldn’t affect you regardless of the quantity you eat. I first made a list of these “free” foods (I’m probably pulling this “free” terminology from early-2000-era diabetes food terminology) that I actually like and want to eat. For example, for me, this was eggs, grits, carrots, baby corn, peanuts, most cheese, and popcorn. This is what I ate for the first handful of days while I was doing my research on what else would constitute a low FODMAP diet. It sounded and felt restrictive, but thankfully as I learned more I realized that I could eat a lot more things and a better diversity of things.

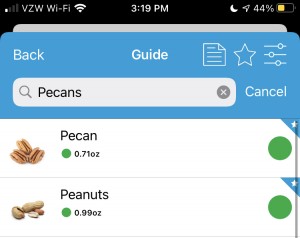

The next app/tool that helped was the Monash app. One caveat – it costs money. I waited a few weeks before I finally caved and paid $8 USD for it. The reason I finally decided to get it (vs using tools like that spreadsheet above and other places that have information from Monash available) is I wanted the quick visual glance the app has about whether the food is completely low FODMAP and ‘free’ to eat (e.g. carrots, eggs) or low FODMAP in certain portion sizes, or pretty much high FODMAP no matter what. Monash is a university in Australia that does most of the research and testing on FODMAPs in foods, so I decided paying for the app was a way to invest in the research that I’m clearly benefiting from.

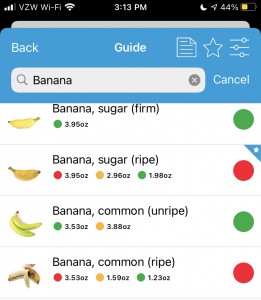

I do have some frustrations with the Monash app, though. It only includes foods that they’ve happened to measure…which is a good amount, but not as many as I’d like. It also confusingly sometimes lists the different serving sizes in opposite order. For example, there might be a “green” overall rating, with a certain portion size indicated in green but also showing the yellow/amber “moderate” amount portion size alongside the red “high” portion size, so you can see the difference. However, sometimes they list the portion size in opposite directions. This search for bananas is a good example – the color indicators on “Banana, sugar (ripe) goes red-amber-green; the color indicators on “Banana, common (unripe)” goes green-amber, and the color indicators on “Banana, common (ripe)” goes red-amber-green again.

Their rationale for this is that standard serving size and traffic light rating will always be the first traffic light so foods may start green and go red as serving sizes increase or start red and become green with smaller servings. However, it means as a user that you have to pay close attention to the order and serving sizes and it’s not the same across the app.

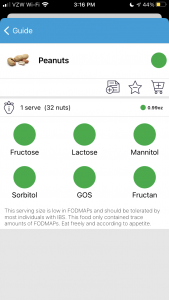

You also have to pay attention to the tiny, grey text at the bottom below the individual ratings. The text isn’t the same from item to item. For example, peanuts are marked as green, no other color rating. When you click to see the details, it shows a portion size of 32 nuts (0.99 ounce), and the text indicates the portion only contains trace amounts of FODMAPs and “eat freely according to appetite”. Same for carrots, so these are what would constitute a “free” food where you don’t have to worry about FODMAP stacking.

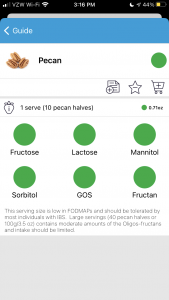

However, when you look at pecans, it also has a green overall rating. But the serving size is 10 pecan halves (0.71 ounce) and the grey text indicates that “Large servings (40 pecan halves or 100g/3.5oz) contains moderate amounts of the Oligos-fructans and intake should be limited.”

This means you can’t just eyeball the app and take the green overall traffic light rating, even if it just has a green overall rating and doesn’t have the additional lights (like under the bananas) indicating warnings about different portion sizes. The warnings about portion sizes may be hidden in the grey text that your brain doesn’t want to read because it assumes the text is always the same.

(The other thing I don’t love about the Monash app is that it’s language is very IBS focused. But there’s a lot of people using low FODMAP for non-IBS reasons, so you can mostly ignore that. It has other tools like a diary for symptoms and food intake and a re-introduction tracker for when you do re-challenges of FODMAPs.)

Another app resource is an app called “Spoonful”. It’s free: although you can pay something like $2.99 for a premium version, the free capabilities suit my purpose. You can scan a barcode or type and search for store-bought products, which is a great use case for me since I don’t cook a lot from scratch. It has different color coding (and you can limit your search to a color type) for whether a given food has low, moderate or high FODMAPs in one serving. It’s supposed to be dietitian-reviewed and approved. It’s good for gut-checking your interpretation of an ingredient label, but there’s a caveat that I’ve found several inconsistencies within the app (and already flagged and reported them). For example, I spotted a chip that was sour cream and onion and supposedly low (green rating) FODMAP *and* cited as officially certified as low FODMAP. Except…it has onion powder as a major ingredient and I am not sure it could be considered low FODMAP. (What I think happened is that Australia’s version of the company has a sour cream and chive chip that looks pretty similar and is certified low FODMAP, and they accidentally swapped them within the app.) I reported that one, and they were quick to fix it within days, so it is now correctly marked as high FODMAP. In another search I did, milk and milk related products are flagged in one flavor of a food (e.g. an ice cream bar), but a slightly different flavor that’s still the same ice cream doesn’t have the milk ingredients flagged and has a completely different color rating as a result with those ingredients not flagged (in the same quantities). A third type of error I have found is that you can scan a barcode of a product, and the labeled ingredients listed in the app do not match the ingredients currently on the package – it’s pulling from a stored list of ingredients that could be outdated. So as a user, you have to eyeball and make sure the app listed ingredients matches the ingredients on the product in your hand, then compare any potential FODMAP-containing ingredients that are either flagged in the app or might be in your hand but not listed on the app, if those ingredient labels differ.

Hypothetically these are medium or small errors, but given the number of errors like that where they inconsistently flag ingredients across the same type of food item that result in variable color ratings, I would not rely just on their color rating and instead double check the ingredients yourself (including comparing them to the version you are holding in your hand). If you’re as sensitive to FODMAPs as I am, it’s worth double checking and thinking it through each time.

Additionally, the Spoonful app (as of August 2021) only supports one diet filter search at a time. Thankfully, I’ve had celiac forever and am comfortable knowing how to also determine if something is gluten free or not. So it’s not a big deal for me to “just” use the low FODMAP search to see what’s FODMAP-y or not, with the above caveats. But low FODMAP does not mean gluten free, even though some wheat-related items are high FODMAP, so do not use anything that’s low FODMAP as an indicator that it’s celiac-safe!

As another way of checking things out, it’s always helpful to google “Ingredient name FODMAP” or “Food name FODMAP” – often there are blog posts discussing the food type, or Reddit or similar forum posts discussing individuals’ experiences with that ingredient or food type.

However, one more important thing to keep in mind: it may be “low FODMAP” or “no FODMAP”, and it can still cause symptoms. Everyone is different, and that’s the point of needing to re-challenge each group to determine what groups bother you, and in what quantities. Additionally, some no-FODMAP foods or ingredients could be bothersome, and it has nothing to do with FODMAPs. For example, I noticed Crystal Light was bothering me last year and stopped drinking it. After I did the first phase of low FODMAP (the elimination phase) for a few weeks, I decided to test Crystal Light since it’s theoretically not containing FODMAP ingredients. However, it definitely caused symptoms that weren’t attributable to anything else, so it’s on my “don’t drink” list, just like onion soup would be, even though Crystal Light isn’t considered to have FODMAPs.

So how exactly do you do the different FODMAP diet phases?

Most everything I read online said the first phase, the elimination phase where you eat 100% low FODMAP, should be around 2-6 weeks. Another piece of data was that many dietitians recommend having 5-7 symptom-free days before starting food re-challenges (e.g. the second or next phase).

If you’re like me, you might get accidentally FODMAP’ed, as I call it, or experience FODMAP stacking by accident within your first few weeks as you work out the correct portion sizes of things and when to eat them. My rule of thumb was aiming for 2 weeks overall on the elimination/first phase, but also going for several days without symptoms so I had a “clean slate”, so to speak, before starting the challenges. I am lucky, relatively speaking, that I don’t have the major symptoms that most people with IBS who do FODMAP seem to experience – I don’t have diarrhea or constipation or that spectrum to deal with. My symptoms are usually noticeable immediately or within 12 hours, but they also resolve pretty quickly, so I can see the correlation between what I eat and the results fairly easily. As a result, I went a little more than 2 weeks attempting to do full low FODMAP elimination, had an extra few days added on due to some accidental FODMAP stacking, before I began my first “challenge” food.

The challenge foods should be ones that only contain one of the FODMAP groups. If you pick something that has multiple FODMAP groups, it’ll be hard to tell which FODMAP you’re reacting to or if it’s the stacking effect. I started with lactose (because I’m pretty confident already that I’m not lactose intolerant and it’s not an issue group for me) because it’s an easy one to start and cross off my list. The others I’ve personally decided to use as my test foods are cashews (Fructan+GOS); Apple (Fructose+Sorbitol); Raisins (Fructan: veggie & fruits); Almonds (GOS); Honey (Fructose); Sweet Potato (Mannitol); and Peach (Sorbitol).

Because I have celiac disease, I am of course skipping wheat bread and wheat pasta (Fructan: grain foods). I’m also skipping the separate fructan test for onions and garlic because I know I react to those and have already reverse-tested eliminating those in the past year. I might eventually test onion powder and garlic powder, but I’m de-prioritizing those to be after I test most of the others.

(The Monash app in the reintroduction section has several foods recommended for each group and the amounts for each, so that’s a good resource for selecting some of the challenge foods).

Two schools of thought for re-challenging: you can do day 1, 2, and 3 in a row with the increasing amount prescribed, or you can do every other day with a “washout” (e.g. fully low FODMAP) day in between. If you have moderate to major symptoms, you stop and have 3 washout days before you proceed with the next test. It’s up to you to decide what symptoms are tolerable and whether you proceed or cross that group off your list (for now). You can always come back and re-challenge or re-test groups or food at any time.

Finally, the third phase is what you get to when you’ve done all your testing and have an idea of what FODMAP groups are irritants or triggers, which foods as a result you want to avoid or continue to experiment with. Ideally, you arrive at a more diverse diet than the full elimination stage of low FODMAP. (Again, I’m not a doctor or dietitian, and I’m DIY-ing my low FODMAP experience, and these are all the conclusions I’ve arrived at after copious reading online and in the medical literature.)

What do you tell family and friends about the low FODMAP diet?

It depends, especially on what your lifestyle is and what stage of the diet that you are at (and also if you’re in a global pandemic which limits your eating-out options).

Because this experience has been during a global pandemic, I am no longer eating out at restaurants (to avoid being unmasked around strangers) which made things easier in the sense that I didn’t have to try to figure out low FODMAP restaurant options. But it was harder because I couldn’t even get gluten free takeout or delivery food anymore, and now have to make all my food myself. For the few social food situations I had with my in-laws (we are all fully vaccinated and use antigen testing to make sure we aren’t infectious on the days we visit in person), I have mostly decided to take my own food. I’ve stashed a few things in the freezer and pantry at their house to be able to make a meal and just let everyone else do takeout without me, so that we can all still sit down together for a meal. I have described what I’m doing and what it entails (such as avoiding onion and garlic and only eating particular things in particular amounts), but it’s hard to describe to most people at a high level because of the complexity of the types of foods (it seems random unless you think about the biochemistry) and the quantities. It makes me nostalgic for explaining only celiac to people, because “gluten free” is a much smaller category of ingredients to watch for and avoid, compared to FODMAPs and FODMAP quantity specifics. That being said, already being gluten free means I’m experienced at reading ingredient labels and have a head start on excluding some of the major FODMAP groups (fructan grain foods are usually gluten) and don’t have to (well, don’t get to) re-test those.

A friend recently said (because she’s amazing) that she wanted to read up on what a low FODMAP diet means, and I couldn’t find a good high level simple article to send to her, so I had to type up an explanation. So what I have summarized to her and family and other friends is this:

- I have GI dysbiosis where I react to a lot of what I’m eating. I’m experimenting with a low FODMAP diet, which starts with a partial elimination diet to restrict the types of FODMAPs that I eat. FODMAPs are certain types of carbs that don’t digest well. During this stage, I’m avoiding things like onion, garlic, certain sweeteners, many fruits, and more. Even small amounts of these ingredients can make me feel bad, just like gluten, although they cause shorter term symptoms. What I can eat freely are plain meat and protein including eggs; vegetables like cucumbers, carrots, potatoes, and baby corn; and cheese, among other things. I need to check the ingredients on everything I eat, even things that we know are already gluten free.

- Eventually, I will begin to “test” my response to the FODMAP foods. I’ll still be carefully managing what I eat while I do these tests so that I have a “clean slate” to see how my body responds to the type and quantity of each food. My hope is to be able to add some of the food groups back into my diet, but it may be only restricted amounts. It will be several months before I progress through all the tests.

- I can use your support – I’m looking for low FODMAP alternatives to foods like X, Y, and Z, so if you’d like to help, in addition to listening to me vent, you could help me research some store-bought or homemade alternatives to these.

(One reason I add the “I can use your support” aspect for some people, which is obviously optional – I learned from being gluten free with celiac that having friends and family aware of what it takes to eat and find safe gluten-free options really cut down on the emotional labor required to find and suggest food every time. People try to be nice and let me offer gluten free options for eating out, but that means I have to do a lot of research every time. Having family members put the “Find Me Gluten Free” app on their phone and teaching them how to do basic searches so they could offer up suggestions, too, made a big difference. I won’t ask everyone for help re: FODMAP but for certain family members, they really can make a difference in doing some of the searching for low FODMAP alternatives to certain things that I haven’t been able to find yet! For me, this is things like finding a low FODMAP steak sauce that I could buy. I still haven’t found one. Thankfully, there’s also brands like Fody where I buy a lot of sauces (BBQ sauce, spaghetti sauce, ketchup) and salad dressings – plus now they have tasty BBQ chips that are also gluten free, and meal delivery services like Epicured that I’ve tried. Note – I am not sponsored or paid by either of those brands, I shell out my own money for them!)

—

At the end of the day, the one thing you need to know about FODMAP is that everyone is different. Literally, you are a scientific experiment of one. What works for someone else doesn’t necessarily work for you. You know you, and you get to decide what level of symptoms you are willing to tolerate – or not – in response to different quantities of food. Whether it’s IBS, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), some other condition, or general gastrointestinal dysbiosis, a low FODMAP diet may be one option that you can try and see if it helps you feel better. In diabetes, we often say “YDMV”, meaning ‘your diabetes may vary’. In the landscape of GI-related stuff, I think it’s “YFWV”, meaning “your FODMAP experience will vary.”

Recent Comments