I was asked to participate in a ‘debate’ about AID at #ADA2023 (ADA Scientific Sessions), representing the perspective that DIY systems should be an option for people living with diabetes.

I present this perspective as a person with type 1 diabetes who has been using DIY AID for almost a decade (and as a developer/contributor to the open source AID systems used in DIY) – please note my constant reminder that I am not a medical doctor.

Dr. Gregory P. Forlenza, an Associate Professor from Barbara Davis Center, presented a viewpoint as a medical doctor practicing in the US.

FYI: here are my disclosures and Dr. Forlenza’s disclosures:

I opened the debate with my initial presentation. I talk about the history of DIY in diabetes going back to the 1970s, when people with diabetes had to “DIY” with blood glucose meters because initially healthcare providers did not want people to fingerstick at home because they might do something with the information. Similarly, even insulin pumps and CGMs have been used in different “DIY” ways over the years – notably, people with diabetes began dosing insulin using CGM data for years prior to them being approved for that purpose. It’s therefore less of a surprise in that context to think about DIY being done for AID. (If you’re reading this you probably also know that DIY AID was done years before commercial AID was even available; and that there are multiple DIY systems with multiple pump and CGM options, algorithms, and phone options).

And, for people with diabetes, using DIY is very similar to how a lot of doctors recommend or prescribe doing things off label. Diabetes has a LOT of these types of recommendations, whether it’s different types of insulins used in pumps that weren’t approved for that type of insulin; medications for Type 2 being used for Type 1 (and vice versa); and other things that aren’t regulatory approved at all but often recommended anyway. For example, GLP-1’s that are approved for weight management and not glycemic control, but are often prescribed for glycemic control reasons. Or things like Vitamin D, which are widely prescribed or recommended as a supplement even though it is not regulatory-approved as a pharmaceutical agent.

I always like to emphasize that although open source AID is not necessarily regulated (but can be: one open source system has received regulatory clearance recently), that’s not a synonym for ‘no evidence’. There’s plenty of high quality scientific evidence on DIY use and non-DIY use of open source AID. There’s even a recent RCT in the New England Journal of Medicine, not to mention several other RCTs (see here and here, plus another pending publication forthcoming). In addition to those gold-standard RCTs, there are also reviews of large-scale big data datasets from people with diabetes using AID, such as this one where we reviewed 122 people’s glucose data representing 46,070 days’ worth of data; or another forthcoming publication where we analyzed the n=75 unique (distinct from the previous dataset) DIY AID users with 36,827 days’ of data (average of 491 days per participant) and also found above goal TIR outcomes (e.g. mean TIR 70-180 mg/dL of 82.08%).

Yet, people often choose to DIY with AID not just for the glucose outcomes. Yes, commercial AID systems (especially now second-generation) can similarly reach the goal of 70+% TIR on average. DIY helps provide more choices about the type and amount of work that people with diabetes have to put IN to these systems in order to get these above-goal OUTcomes. They can choose, overall or situationally, whether to bolus, count carbs precisely, announce meals at all, or only announce relative meal size while still achieving >80% TIR, no or little hypoglycemia, and less hyperglycemia. Many people using DIY AID for years have been doing no-bolus and/or no meal announcements at all, bringing this closer to a full closed loop, or at least, an AID system with very, very little user input required on a daily basis if they so choose. I presented data back in 2018(!) showing how this was being done in DIY AID, and it was recently confirmed in a randomized control trial (hello, gold standard!) showing that between traditional use (with meal announcements and meal boluses); meal announcement only (no boluses); and no announcement nor bolusing, that they all got similar outcomes in terms of TIR (all above-goal). There was also no difference in those modes of total daily insulin dose (TDD) or amount of carb intake. There was a small difference in time below range being slightly higher in the first mode (where people were counting carbs and bolusing) as compared to the other two modes – which suggests that MORE user input may actually be limiting the capabilities of the system!

The TLDR here is that people with diabetes can do less work/provide less input into AID and still achieve the same level of ideal, above-goal outcomes – and ongoing studies are showing the increased QOL and other patient-reported outcomes that also improve as a result.

Again, people may be predisposed to think that the main difference between commercial and DIY is whether or not it is regulatory approved (and therefore prescribable by doctors and able to be supported by a company under warranty); the bigger differences are instead around interoperability across devices, data access, and transparency of how the system works.

There’s even an international consensus statement on open source AID, created by an international group of 48 medical and legal experts, endorsed by 9 national and international diabetes organizations, supporting that open source AID used in DIY AID is a safe and effective treatment option, confirming that the scientific evidence exists and it has the potential to help people with diabetes and reduce the burden of diabetes. They emphasize that doctors should support patient (and caregiver) autonomy and choice of DIY AID, and state that doctors have a responsibility to learn about all options that exist including DIY. The consensus statement is focused on open source AID but also, in my opinion, applies to all AID: they say that AID systems should fully disclose how they operate to enable informed decisions and that all users should have real-time and open access to their own data. Yes, please! (This is true of DIY but not true of all commercial systems.)

The elephant in the room that I always bring up is cost, insurance coverage, and therefore access and accessibility of AID. Many places have government or insurance that won’t cover AID. For example, the proposed NICE guidelines in the UK wouldn’t provide AID to everyone who wants one. In other places, some people can get their pump covered but not CGM, or vice versa, and must pay out of pocket. Therefore in some cases, DIY has out of pocket costs (because it’s not covered by insurance), but is still cheaper than AID with insurance coverage (if it’s even covered).

I also want to remind everyone that choosing to DIY – or not – is not a once-in-a-lifetime decision. People who use DIY choose every day to use it and continue to use it; at any time, they could and some do choose to switch to a commercial system. Others try commercial, switch back to DIY, and switch back and forth over time for various reasons. It’s not a single or permanent decision to DIY!

The key point is: DIY AID provides safety and efficacy *and* user choice for people with diabetes.

—

Dr. Forlenza followed my presentation, talking about commercial AID systems and how they’ve moved through development more quickly recently. He points to the RCTs for each approved commercial system that exist, saying commercial AID systems work, and describing different feature sets and variety across commercial systems. He shared his thoughts on advantages of commercial systems including integration between components by the companies; regulatory approval meaning these systems can be prescribed by healthcare providers; company-provided warranties; and company provided training and support of healthcare providers and patients.

He makes a big point about a perceived reporting bias in social media, which is a valid point, and talks about people who cherry pick (my words) data to share online about their TIR.

He puts an observational study and the CREATE Trial RCT data up next to the commercial AID systems RCT data, showing how the second generation commercial AID reach similar TIR outcomes.

He then says “what are you #notwaiting for?”, pointing out in the US that there are 4 commercial systems FDA approved for type 1 diabetes. He says “Data from the DIY trials themselves demonstrate that DIY users, even with extreme selection bias, do not achieve better glycemic control than is seen with commercial systems.” He concludes that commercial AID has a wide variety of options; commercial systems achieve target-level outcomes; a perception that both glucose outcomes and QOL are being addressed by the commercial market, and that “we do not need Unapproved DIY solutions in this space”.

—

After Dr. Forlenza’s presentation, I began my rebuttal, starting with pointing out that he is incorrectly conflating perceived biases/self-reporting of social media posts with gold-standard, rigorously performed scientific trials evaluating DIY. Data from DIY AID trials do not suffer from ‘selection bias’ any more than commercial AID trials do. (In fact, all clinical trials have their own aspects of selection bias, although that isn’t the point here.) I reminded the audience of the not one but multiple RCTs available as well as dozens of other prospective and retrospective clinical trials. Plus, we have 82,000+ data points analyzed showing above-goal outcomes, and many studies that evaluate this data and adjust for starting outcomes still show that people with diabetes who use DIY AID benefit from doing so, regardless of their starting A1c/TIR or demographics. This isn’t cherry-picked social media anecdata.

When studies are done rigorously, as they have been done in DIY, we agree that now second-generation commercial AID systems reach (or exceed, depending on the system) ADA standard of care outcomes. For example, Dr. Forlenza cited the OP5 study with 73.9% TIR which is similar to the CREATE Trial 74.5% TIR.

My point is not that commercial systems don’t work; my point is that DIY systems *do* work and that the fact that commercial systems work doesn’t then override the fact that DIY systems have been shown to work, also! It’s a “yes, and”! Yes, commercial AID systems work; and yes, DIY AID systems work.

The bigger point, which Dr. Forlenza does not address, is that the person with diabetes should get to CHOOSE what is best for them, which is not ONLY about glucose outcomes. Yes, a commercial system- like DIY AID – may help someone get to goal TIR (or above goal), but DIY provides more choice in terms of the input behaviors required to achieve those outcomes! There’s also possible choice of systems with different pumps or CGMs, different (often lower) cost, increased data access and interoperability of data displays, different mobile device options, and more.

Also, supporting user choice of DIY is in fact A STANDARD OF CARE!

It’s in the ADA’s Standards of Care, in fact, as I wrote about here when observing that it’s in the 2023 Standards of Care…as well as in 2022, 2021, 2020, and 2019!

I wouldn’t be surprised if there are people attending the debate who think they don’t have any – or many – patients using DIY AID. For those who think that (or are reading this thinking the same), I ask a question: how many patients have you asked if they are using DIY AID?

There’s a bunch of reasons why it may not come up, if you haven’t asked:

- They may use the same consumables (sites, reservoirs) with a different or previous pump in a DIY AID system.

- Their prescribed pump (particularly in Europe and non-US places that have Bluetooth-enabled pumps) may be usable in a DIY AID.

- They may not be getting their supplies through insurance, so their prescription doesn’t match what they are currently using.

- Or, they have more urgent priorities to discuss at appointments, so it doesn’t come up.

- Or, it’s also possible that it hasn’t come up because they don’t need any assistance or support from their healthcare provider.

Speaking of learning and support, it’s worth noting that in DIY AID, because it is open source and the documentation is freely available, users typically begin learning more about the system prior to initiating their start of closed loop (automated insulin delivery). As a result, the process of understanding and developing trust in the system begins prior to closed loop start as well. In contrast, much of the time there is limited available education prior to receiving the prescription for a commercial AID; it often aligns more closely with the timeline of starting the device. Additionally, because it is a “black box” with fewer available details about exactly how it works (and why), the process of developing trust can be a slower process that occurs only after a user begins to use a commercial device.

I closed my rebuttal section by asking a few questions out loud:

I wonder how healthcare providers feel when patients learn something before they do – which is often what happens with DIY AID. Does it make you uncomfortable, excited, curious, or some other feeling? Why?

I encouraged healthcare providers to consider when they are comfortable with off-label prescriptions (or recommending things that aren’t approved, such as Vitamin D), and reflect on how that differs from understanding patients’ choices to DIY.

I also prompted everyone to consider whether they’ve actually evaluated (all of) the safety and efficacy data, of which many studies exist. And to consider who benefits from each type of system, not only commercial/DIY but individual systems within those buckets. And to consider who gets offered/prescribed AID systems (of any sort) and whether subconscious biases around tech literacy, previous glucose outcomes, and other factors (race, gender, other demographic variables) result in particular groups of people being excluded from accessing AID. I also remind everyone to think about what financial incentives influence access and available of AID education, and where the education comes from.

—

Although Dr. Forlenza’s rebuttal followed mine, I’ll summarize it here before finishing a recap of my rebuttal: he talks about individual selection bias/cherry picked data, acknowledging it can occur in anecdotes with commercial systems as well; talks about the distinction of regulatory approval vs. off label and unapproved; legal concerns for healthcare providers; and closes pointing out that many PWD see primary care providers, he doesn’t believe it is reasonable to expect PCPs to become familiar with DIY since there are no paid device representatives to support their learning, and that growth of AID requires industry support.

—

People probably wanted to walk out of this debate with a black and white, clear answer on what is the ‘right’ type of AID system: DIY or commercial. The answer to that question isn’t straightforward, because it depends.

It depends on whether a system is even AVAILABLE. Not all countries have regulatory-approved systems available, meaning commercial AID is not available everywhere. Some places and people are also limited by ACCESSIBILITY, because their healthcare providers won’t prescribe an AID system to them; or insurance won’t cover it. AFFORDABILITY, even with insurance coverage, also plays a role: commercial AID systems (and even pump and CGM components without AID) are expensive and not everyone can afford them. Finally, ADAPTABILITY matters for some people, and not all systems work well for everyone.

When these factors align – they are available, accessible, affordable, and adaptable – that means for some people in some places in some situations, there are commercial systems that meet those needs. But for other people in other places in other situations, DIY systems instead or also can meet that need.

The point is, though, that we need a bigger overlap of these criteria! We need MORE AID systems to be available, accessible, affordable, and adaptable. Those can either be commercial or DIY AID systems.

The point that Dr. Forlenza and I readily agree on is that we need MORE AID – not less.

This is why I support user choice for people with diabetes and for people who want – for any variety of reasons – to use a DIY system to be able to do so.

—

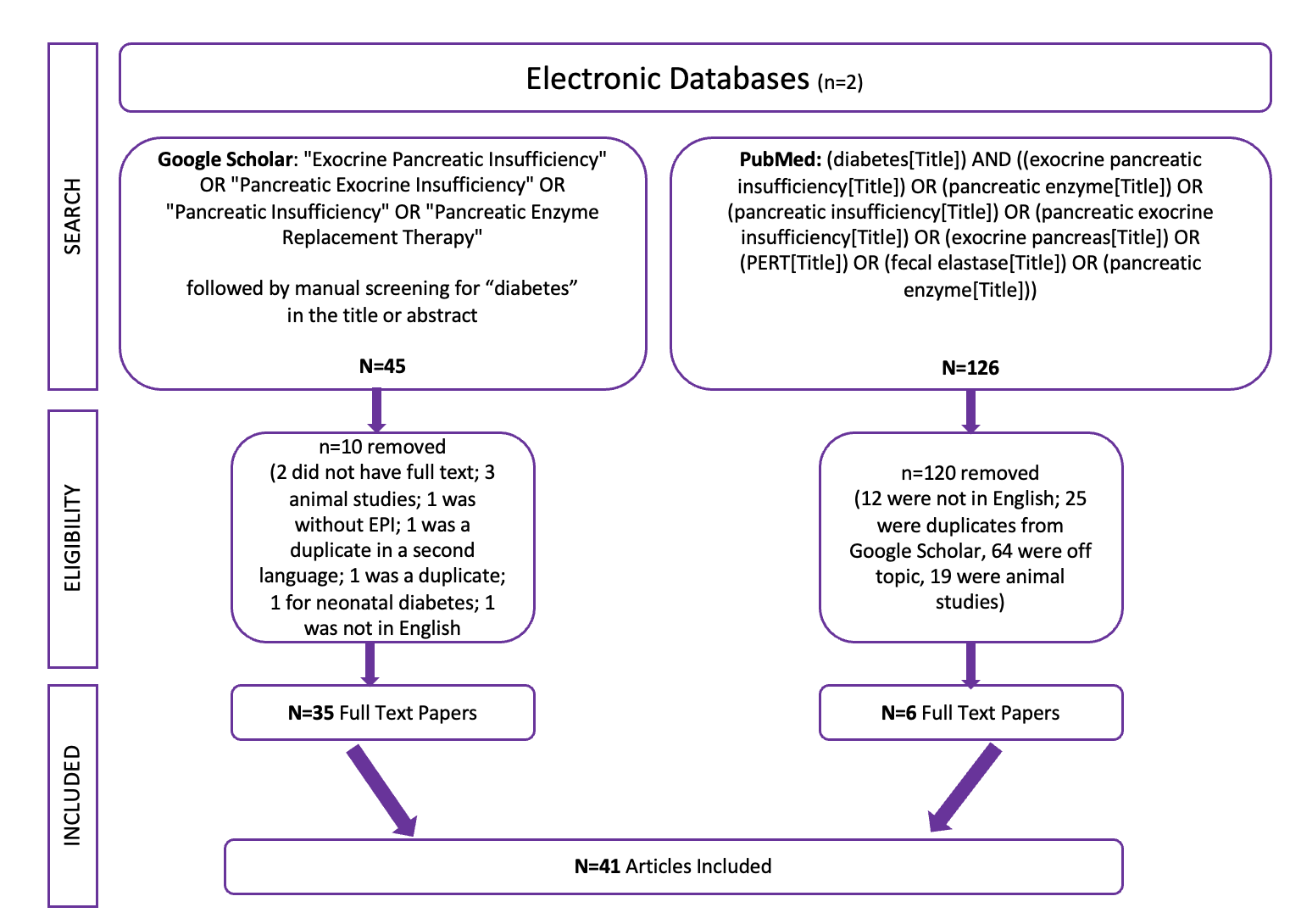

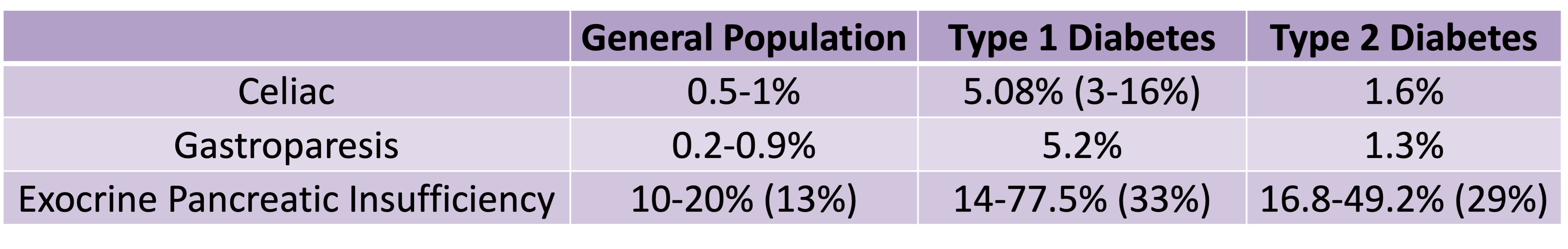

PS – I also presented a poster at #ADA2023 about the high prevalence rates of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI / PEI / PI) in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes – you can find the poster and a summary of it here.

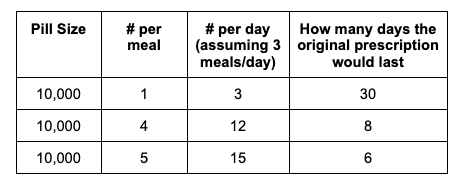

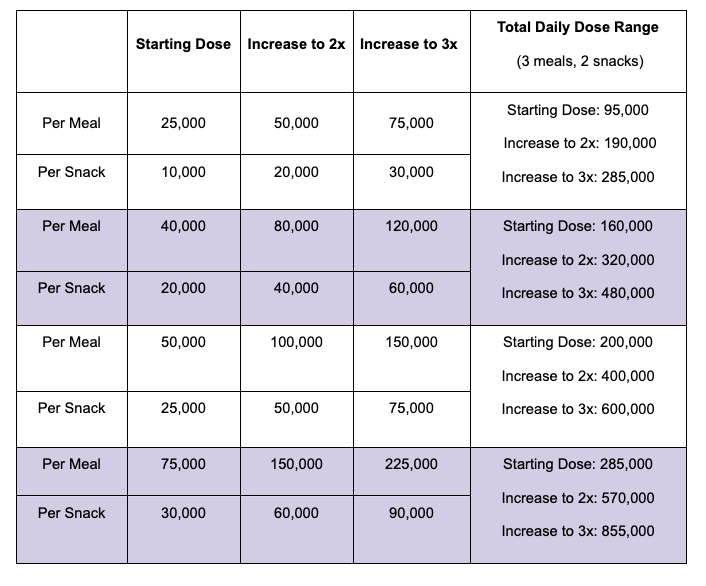

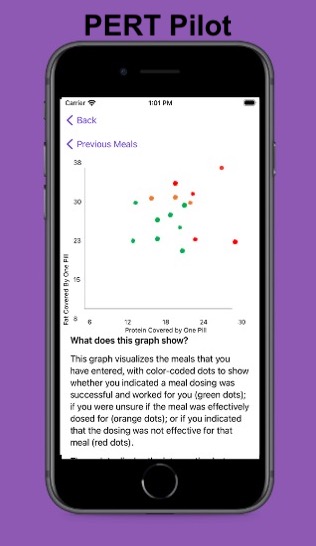

For example, I was initially prescribed an enzyme dose that was one pill per meal (and no snacks), so I had 3 pills per day. But I quickly found myself needing two pills per meal, based on what I was typically eating. I summarized my data to my doctor, saying that I found one pill typically covered up to ~30 grams of fat per meal, but most of my meals were >30 grams of fat, so that I wanted to update my prescription to have an average of 2 pills per meal of this prescription size. I also wanted to be able to eat snacks, so I asked for 2 pills per meal, 1 per snack, which meant that my prescription increased to 8 pills per day (of the same size), to cover 2 pills x 3 meals a day (=6) plus up to 2 snacks (=2). I also had weeks of data to show that my average meal was >30 grams of fat to confirm that I need more than the amount of lipase I was originally prescribed. My doctor was happy to increase my prescription as a result, and this is what I’ve been using successfully for over a year ever since.

For example, I was initially prescribed an enzyme dose that was one pill per meal (and no snacks), so I had 3 pills per day. But I quickly found myself needing two pills per meal, based on what I was typically eating. I summarized my data to my doctor, saying that I found one pill typically covered up to ~30 grams of fat per meal, but most of my meals were >30 grams of fat, so that I wanted to update my prescription to have an average of 2 pills per meal of this prescription size. I also wanted to be able to eat snacks, so I asked for 2 pills per meal, 1 per snack, which meant that my prescription increased to 8 pills per day (of the same size), to cover 2 pills x 3 meals a day (=6) plus up to 2 snacks (=2). I also had weeks of data to show that my average meal was >30 grams of fat to confirm that I need more than the amount of lipase I was originally prescribed. My doctor was happy to increase my prescription as a result, and this is what I’ve been using successfully for over a year ever since.

Recent Comments