Living with diabetes is expensive. However, the cost and price goes beyond the cost of insulin, which you may have heard about lately. In addition to insulin, you need tools and supplies to inject the insulin (e.g. syringes, insulin pens, or an insulin pump). Depending on those methods, you need additional supplies (e.g. pen needles for insulin pens, reservoirs and infusion sets for insulin pumps). You also need blood glucose monitoring supplies, whether that is meter and up to a dozen glucose test strips a day and/or a continuous glucose monitor which is made up of a disposable sensor and a reusable transmitter.

All those costs add up on a daily basis for people living with diabetes, even if you have health insurance.

Understanding the costs of living with chronic illness with health insurance in the US

Every year in the US we have “open enrollment” time when we opt-in or enroll into our choice of health insurance plan for the following year. I am lucky and have access to insurance through my husband’s employer, who covers part of the cost for him and me (as a spouse). We have a high-deductible (HSA-qualified) health plan, so our deductible (the amount we must pay before insurance begins to pay for a portion of the costs) is usually around $1,500-$2,500 USD for me. After that, I might pay either a fixed copay ($10 or $25 or similar) for a doctor’s visit, or a percentage (10% or 20%) while the insurance covers the rest of the cost. Then there is a fixed “out of pocket (OOP) max” cost for the year, which might be something like $3,000 USD total. Sometimes the OOP max is pretty close to the deductible, because we typically choose the ‘high deductible’ plan (with no monthly cost for the insurance plan) over a plan where we have a lower deductible but pay a monthly premium for the insurance.

That’s a very rough summary of how I see my health insurance. Everyone has different health insurers (the company providing the insurance) and different plans (the costs will be different based on whether it’s through a different employer or if it’s an individual plan).

So the costs to people with diabetes can vary quite a bit in the US, depending on whether you have insurance: there is variation in the monthly cost of the plan, the amount of the deductible, and the amount of the out of pocket max.

In order to choose my plan for the following year, I look at the total cost for the year of my health supplies and health care, then look at the plans. Usually, the high deductible plan “feels” more expensive because I might have to reach $2,500 before insurance kicks in; however, the out of pocket cap may only be $500 beyond that, so that I’m going to pay a maximum of $3,000 for the year in insurance-covered costs*. There are other types of plans that are lower deductible, such as insurance kicking in after a $250 deductible. That sounds better, right? Well, those plans come with a monthly cost (premium) of $250. So you need to factor that in ($250×12=$3,000) alongside the deductible and any costs up to the out of pocket max ($2,500). From this, you’d pay the $3,000 total yearly premium plus up to $2,500 OOP, or $5,500. Thus, even though it has a lower deductible and OOP, you’re in total paying much more ($5,500 vs $3,000) if you’re someone like me.

Why? Because I have >$3,000 of health supply costs every year.

This is why every few years (mostly after I forget what I learned the last time), I do the math on how much my supply costs to see if I’m still making the most cost-effective choices for me with my insurance plans.

I wanted to share this math methodology below, also because this year I have new variables, which are two new chronic diseases (exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and Graves) that add additional costs and healthcare needs and require me to want to re-check my math.

* Clarifying that previously and most years I pay out of pocket for minor, relatively low-cost health supplies like vitamins or tape to cover my CGM that I buy and do not get through insurance coverage, so my total costs are usually over that OOP max, but likely not by more than a few hundred dollars.

—

Note: Do not attempt to use this as an absolute cost of diabetes for anyone else. These numbers are based on my use cases in terms of volume of insulin, insurance coverage, etc. Ditto for trying to use the costs for EPI. Where relevant below, I provide rough estimates of my methodology so that another individual with diabetes or EPI/PEI could use similar methods to calculate their own rough costs, if they wished. However, this cannot be used to determine any average cost to people with diabetes more broadly, so don’t excerpt or cite this in those ways. This is purely n=1 math with conclusions that are unique to this n=1 (aka me) but with methods that can be extended for others.

—

I’ll cover my estimates for costs of diabetes, celiac, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI or PEI), and Graves’ disease below. This doesn’t account for visits (e.g. doctor’s appointments), lab tests, or other health costs such as x-rays for breaking bones, because those vary quite a bit year to year and aren’t guaranteed fixed costs. But the supplies I need for diabetes, EPI, etc are fixed costs, which I use to anchor my math. Given that they end up well above my OOP max, the then-variable amount of other costs (doctor’s appointments, lab work, etc) is minor in comparison and irrelevant regardless of how much it varies year to year.

The costs (for me) of daily living with diabetes

(You read the caveat note above, right? This is my math based on my volume of insulin, food intake, personal insulin sensitivity, etc. Lots of variables, all unique to me.)

To calculate the yearly costs of living with diabetes, I make a list of my diabetes supplies.

Primarily for me, those are:

- Insulin

- CGM sensors

- CGM transmitter

- Pump sites

- Reservoirs

(Not included: meter/test strips or the cost of a pump or the cost of any hardware I’m using for my open source automated insulin delivery. I’ve not bought a new in-warranty pump in years, and that alone takes care of the OOP max on my insurance plan if I were to buy a pump that year. Anyway, the above list is really my recurring regular costs, but if you were purchasing a pump or on a subscription plan for a pump, you’d calculate that in as well).

First, I calculate the daily cost of insulin. I take the cost of a vial of my insulin and divide it by 1,000, because that’s how many units a vial of insulin has. Then I multiply that by the average number of units I use per day to get the cost per day of insulin, which for me is $4.36. (The yearly cost of insulin would be $1,592.)

Then, I calculate my CGM sensors. I take the total cost for a 3 month order of sensors and divide by the number of sensors; then divide by 10 days (because a sensor lasts about 10 days) to get the cost per day of a CGM sensor: about $11 per day. But, you also have to add in the cost of the re-usable transmitter. Again, factor the cost of a transmitter over the number of days it covers; for me it’s about $2 per day. In total, the cost per day of CGM is about $13 and the yearly cost of CGM is roughly $4,765.

Next is pump sites and reservoirs. You need both to go with your insulin pump: the pump site is the catheter site into your body and the tubing (this cumulatively gets replaced every few days), and the reservoir is disposable and is filled with insulin. The cost per day of pump sites and reservoirs is about $6 ($4.67 for a pump site and $1.17 for a reservoir) and the yearly cost of pump sites and reservoirs is $2,129.

If you add up these supplies (pump sites and reservoirs, CGM sensor and transmitter, insulin), the daily cost of diabetes for me is about $23. The yearly cost of diabetes for me is $8,486.

Give that $8,486 is well over the out of pocket max cost of $3,000, you can see why that for diabetes alone there is reason to pick the high deductible plan and pay a max of $3,000 for these supplies out of pocket.

—

The daily and yearly costs of living with celiac disease

But I don’t just have type 1 diabetes, so the above are not my only health supply costs.

I also have celiac disease. The treatment is a 100% gluten free diet, and eating gluten free is notoriously more expensive than the standard cost of food, whether that is groceries or eating out.

However, the cost of gluten free food isn’t covered by health insurance, so that doesn’t go in my cost calculation toward pricing the best insurance plan. Yet, it does go into my “how much does it cost every day from my health conditions” mental calculation.

I recently looked at a blog post that summarized the cost of gluten free groceries by state compared to low/medium/high grocery costs for the average person. By extrapolating my state’s numbers from a high-cost grocery budget, plus adding $5 each for eating out twice a week (typically gluten free food has at least a $2-3 surcharge in addition to being at higher cost restaurants, plus the fact that I can’t go eat at most drive-throughs, which is why I use $5/meal to offset the combined cost of the actual surcharge plus my actual options being more expensive).

I ended up estimating about a $3 daily average higher cost of being gluten free, or $1,100 per year cost of eating gluten free for celiac.

That’s probably an underestimate for me, but to give a ballpark, that’s another $1,000 or more I’m paying out of pocket in addition to healthcare costs through insurance.

—

The daily and yearly cost of living with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and the daily and yearly cost of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy

I spent a pleasant (so to speak) dozen or so years when “all” I had to pay for was diabetes supplies and gluten free food. However, in 2022, I was diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (and more recently also Graves’ disease, more on that cost below) and because I have spent ~20 years paying for diabetes, I wasn’t super surprised at the costs of EPI/PEI. However, most people get extreme sticker shock (so to speak) when they learn about the costs of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT).

In summary, since most people don’t know about it: exocrine pancreatic insufficiency occurs for a variety of reasons, but is highly correlated with all types of diabetes, celiac, and other pancreatic conditions. When you have EPI, you need to take enzymes every time you eat food to help your body digest fat, protein, and carbohydrates, because in EPI your pancreas is not producing enough enzymes to successfully break down the food on its own. (Read a lot more about EPI here.)

Like diabetes, where different people may use very different amounts of insulin, in EPI people may need very different amounts of enzymes. This, like insulin, can be influenced by their body’s makeup, and also by the composition of what they are eating.

I use PERT (pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy) to also describe the prescription enzyme pills used for EPI. There are 6 different brands approved by the FDA in the US. They also come in different sizes; e.g. Brand A has 3,000, 6,000, 12,000, 24,000, 36,000 size pills. Those size refer to the units of lipase. Brand B has 3,000, 5,000, 10,000, 15,000, 20,000, 25,000, 40,000. Brands C, D, E and F have similar variety of sizes. The point is that when people compare amounts of enzymes you need to take into account 1) how many pills are they taking and 2) how much lipase (and protease and amylase) each of those pills are.

There is no generic for PERT. PERT is made from ground up pig pancreas. It’s expensive.

There are over the counter (OTC) enzymes made from alternative (plant etc) sources. However, there are ZERO studies looking at safety and efficacy of them. They typically contain much less lipase per pill; for example, one OTC brand pill contains 4,000 units of lipase per pill, or another contains 17,500 units of lipase per pill.

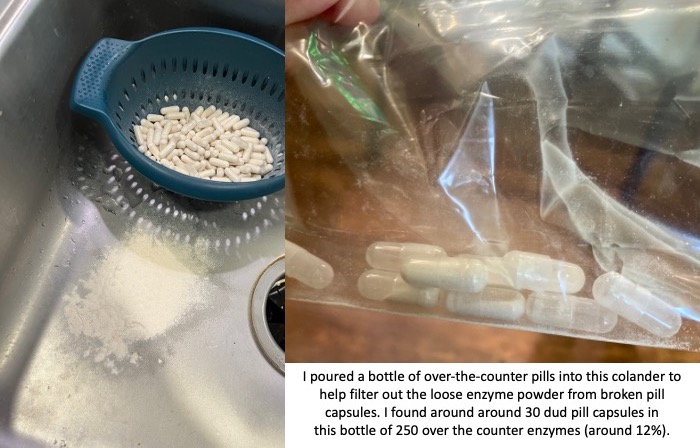

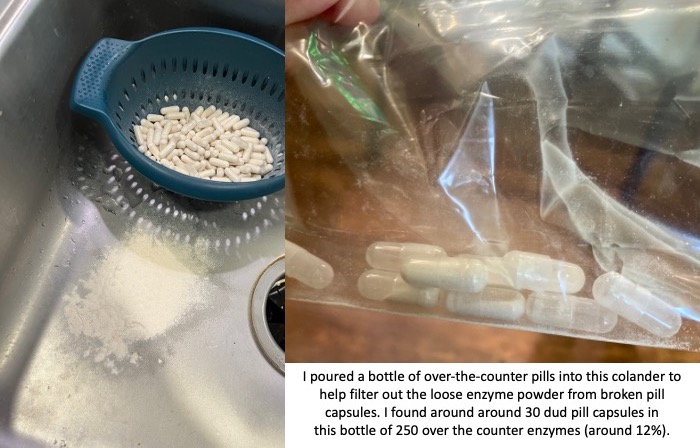

You also need to factor in the reliability of these non-approved pills. The quality of production can vary drastically. I had one bottle of OTC pills that was fine; then the next bottle of OTC pills I started to find empty capsules and eventually dumped them all out of the bottle and actually used a colander to filter out all of the enzyme powder from the broken capsules. There were more than 30 dud pill capsules that I found in that batch; in a bottle of 250 that means around 12% of them were unusable. That makes the reliability of the other ones suspect as well.

If the reliability of these pills even making it to you without breaking can be sketchy, then you need to assume that the counts of how much lipase (and protease and amylase) may not be precisely what the label is reporting. Again, there have been no tests for efficacy of these pills, so anyone with EPI or PEI needs to use these carefully and be aware of these limitations.

This unreliability isn’t necessarily true of all brands, however, or all types of OTC enzymes. That was a common brand of pancrelipase (aka contains lipase, protease, and amylase). I’ve had more success with the reliability of a lipase-only pill that contains about 6,000 units of lipase. However, it’s more expensive per pill (and doesn’t contain any of the other enzymes). I’ve used it to “top off” a meal with my prescription PERT when my meal contains a little bit more fat than what one PERT pill would “cover” on its own.

This combination of OTC and prescription PERT is where the math starts to get complicated for determining the daily cost and yearly cost of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.

Let’s say that I take 6-8 prescription PERT pills every day to cover what I eat. It varies because I don’t always eat the same type or amount of food; I adjust based on what I am eating.

The cost with my insurance and a 90 day supply is $8.34 for one PERT pill.

Depending on whether I am eating less fat and protein on a particular day and only need 6 PERT, the cost per day of enzymes for EPI might be $50.04, whereas if I eat a little more and need 8 PERT, the cost per day of enzymes for EPI could be up to $66.72.

The costs per year of PERT for EPI then would range from $18,000 (~6 per day) to $24,000 (~8 per day).

Please let that sink in.

Eighteen to twenty four thousand dollars to be able to successfully digest my food for a single year, not taking into account the cost of food itself or anything else.

(See why people new to EPI get sticker shock?!)

Even though I’m used to ‘high’ healthcare costs (see above estimates of $8,000 or more per year of diabetes costs), this is a lot of money. Knowing every time that I eat it “costs” at least one $8.34 pill is stressful. Eating a bigger portion of food and needing two or three pills? It really takes a mental toll in addition to a financial cost to think about your meal costing $25.02 (for 3 pills) on top of the cost of the food itself.

This is why OTC pills are interesting, because they are drastically differently priced. The 4,000 unit of lipase multi-enzyme pill that I described costs $0.09 per pill, which is about $0.02 per 1000 units of lipase. Compared to my prescription PERT which is $0.33 per 1000 units of lipase, it’s a lot cheaper.

But again, check out those pictures above of the 4,000 units of lipase OTC pills. Can you rely on those?

Not in the same way you can with the prescription PERT.

In the course of taking 1,254 prescription PERT pills this year (so far), I have not had a single issue with one of those pills. So in part the high cost is to ensure the safety and efficacy. Compare that to 12% (or more) of the OTC pills being complete duds (empty pill capsules that have emptied their powder into the bottle) and some % of unreliability even with a not-broken capsule.

Therefore it’s not feasible to me to completely replace prescription PERT with OTC pills, although it’s tempting purely on price.

I previously wrote at a high level about the cost calculations of PERT, but given my desire to look at the annual cost for estimating my insurance plan (plus many more months of data), I went deeper into the math.

I need to take anywhere from 2-6 OTC pills (depending on the brand and size) to “match” the size of one PERT. I found a new type (to me) of OTC pills that are more units of lipase (so I need 2 to match one PERT) instead of the two other kinds (which took either 4 or 6 to match one PERT), which would enable me to cut down on the number of pills swallowed.

The number of pills swallowed matters.

So far (as of mid-November, after starting PERT in early January), I have swallowed at least 1,254 prescription PERT enzyme pills. I don’t have as much precision of numbers on my OTC pills because I don’t always log them (there’s probably a few dozen I haven’t written down, but I probably have logged 95% of them in my enzyme tracking spreadsheet that I use to help calculate the amount needed for each meal/snack and also to look at trends.), but it’s about 2,100 OTC enzyme pills swallowed.

This means cumulatively this year (which is not over), I have swallowed over 3,300 enzyme pills. That’s about 10 enzyme pills swallowed every day!

That’s a lot of swallowing.

That’s why switching to a brand that is more units of lipase per pill, where 2 of these new OTC kind matches one PERT instead of 4-6, is also significant. While it is also slightly cheaper than the combination of the two I was using previously (a lipase-only and a multi-enzyme version), it is fewer pills to achieve the same amount.

If I had taken prescription PERT instead of the OTCs, it would have saved me over 1,600 pills to swallow so far this year.

You might be thinking: take the prescription PERT! Don’t worry about the OTC pills! OMG that’s a lot of pills.

(OMG, it *is* a lot of pills: I think that as well now that I’m adding up all of these numbers.)

Thankfully, so far I am not having issues with swallowing these pills. As I get older, that might change and be a bigger factor in determining my strategy for how I dose enzymes; but right now, that’s not the biggest factor. Instead, I’m looking at efficacy (getting the right amount of enzymes to match my food), the cost (in terms of price), and then optimizing and reducing the total number of pills if I can. But the price is such a big variable that it is playing the largest role in determining my strategy.

How should we collectively pay for this?

You see, I don’t have EPI in a vacuum.

As I described at the top of the post, I already have $8,000+ of yearly diabetes costs. The $18,000 (or $24,000 or more) yearly enzyme costs are a lot. Cumulatively, just these two alone mean my supply costs are $26-32,000 (or more), excluding other healthcare costs. Thankfully, I do have insurance to cover costs after I hit my out of pocket max, but the bigger question is: who should be paying for this?

If my insurer pays more, then the employer pays more, which means employees get worse coverage on our pooled insurance plan. Premiums go up and/or the plans cover less, and the out of pocket costs to everyone goes up.

So while it is tempting to try to “stuff” all of my supply needs into insurance-covered supplies, in order to reduce my personal out of pocket costs in the short run, that raises costs for everyone in the long run.

This year, for all of those (remember I estimated 2,100 OTC pills swallowed to date) OTC pills I bought, it cost me $515. Out of pocket. Not billed through insurance; they know nothing about it.

It feels like a lot of money. However, if you calculate how many PERT it replaced and the cost per PERT pill, I saved $4,036 by swallowing 1,652 extra pills.

Is paying $500 to save everyone else $4000 worth it?

I think so.

Again, the “price” question gets interesting.

The raw costs of yearly supplies I don’t pay completely; remember with health insurance I am capped at $3,000 out of pocket for supplies I get through insurance. However, again, it’s worth considering that additional costs do not cost me but they cost the insurer, and therefore the employer and our pool of people in this insurance plan and influences future costs for everyone on insurance. So if I can afford (although I don’t like it) $500-ish out of pocket and save everyone $4,000 – that’s worth doing.

Although, I think I can improve on that math for next year.

I was taking the two OTC kinds that I had mentioned: one that was lipase-only and very reliable, but $0.28/pill or $0.04 per 1000 units of lipase (and contains ~6000 units of lipase). The less reliable multi-enzyme pill was cheaper ($.09) per pill but only contains 4000 units of lipase, and was $.02 per 1000 units of lipase. That doesn’t factor in the duds and the way I had to increase the number of pills to account for the lack of faith I had in the 4000 units of lipase always being 4000 units of lipase.

The new OTC pill I mentioned above is $0.39 per pill, which is fairly equivalent price to a combined lipase-only and multi-enzyme pill. In fact, I often would take 1+1 for snacks that had a few grams of protein and more than a few grams of lipase. So one new pill will cover 17,000 units of lipase (instead of 10,000, made up of 6000+4000) at a similar cost: $0.39 instead of $0.36 (for the two combined). And, it also has a LOT more protease per pill, too. It has >2x the amount of protease as the multi-enzyme OTC pill, and is very similar to the amount of protease in my prescription PERT! I’ve mostly discussed the math by units of lipase, but I also dose based on how much protein I’m eating (thus, protease to cover protein the way lipase covers fat digestion), so this is also a benefit. As a result, two of the new OTC pill now more than match 1 PERT on lipase, double the protease to 1 PERT, and is only two swallows instead of the 4-6 swallows needed with the previous combination of OTCs.

I have only tested for a few days, but so far this new OTC is working fairly well as a substitute for my previous two OTC kinds.

Given the unreliability of OTCs, even with different brands that are more reliable than the above picture, I still want to consume one prescription PERT to “anchor” my main meals. I can then “top off” with some of the new OTC pills, which is lower price than more PERT but has the tradeoff cost of slightly less reliability compared to PERT.

So with 3 main meals, that means at least 3 PERT per day ($8.34 per pill) at $25.02 per day in prescription PERT costs and $9,132 per year in prescription PERT costs. Then to cover the additional 3-5 PERT pills I would otherwise need, assuming 2 of the new OTC covers 1 PERT pills, that is 6-10 OTC pills.

Combined, 3 PERT + 6 OTC pills or 3 PERT + 10 OTC pills would be $27.36 or $28.92 per day, or $9,986 or $10,556 per year.

Still quite a bit of money, but compared to 6-8 PERT per day (yearly cost $18,264 to $24,352), it saves somewhere between $7,708 per year (comparing 6 PERT to 3 PERT + 6 OTC pills per day) all the way up to $14,366 per year (comparing 8 PERT to 3 PERT +10 OTC pills per day).

And coming back to number of pills swallowed, 6 PERT per day would be 2,190 swallows per year; 8 PERT pills per day is 2,920 swallows per year; 3 PERT + 6 OTC is 9 pills per day which is 3,285 swallows per year; and 3 PERT + 10 OTC is 13 swallows per day which is 4,745 swallows per year.

That is 1,095 more swallows per year (3PERT+6 OTC vs 6 PERT) or 1,825 more swallows per year (3 PERT + 10 OTC vs 8 PERT).

Given that I estimated I swallowed ~10 enzyme pills per day this year so far, the estimated range of 9-13 swallows with the combination of PERT and OTC pills (either 3 PERT + (6 or 10) OTC) for next year seems reasonable.

Again, in future this might change if I begin to have issues swallowing for whatever reason, but in my current state it seems doable.

—

The daily and annual costs of thyroid treatment for Graves’ Disease

No, we’re still not done yet with annual health cost math. I also developed Graves’ disease with subclinical hyperthyroidism this year, putting me to a grand total of 4 chronic health conditions.

Luckily, though, the 4th time was the charm and I finally have a cheap(er) one!

My thyroid med DOES have a generic. It’s cheap: $11.75 for 3 months of a once-daily pill! Woohoo! That means $0.13 per day cost of thyroid treatment and $48 per year cost of thyroid treatment.

(Isn’t it nice to have cheap, easy math about at least one of 4 things? I think so!)

—

Adding up all the costs of diabetes, celiac disease, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and Graves’ Disease

High five if you’ve read this entire post; and no problem if you skimmed the sections you didn’t care about.

Adding it all up, my personal costs are:

- Diabetes: $23.25 per day; $8,486 per year

- Celiac: $3 per day; $1,100 per year (all out of pocket)

- Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency:

- Anywhere from $50.04 up to $66.72 per day with just prescription PERT pills; $18,265 (6 per day) to $24,353 (8 per day) per year

- With a mix of prescription and OTC pills, $27.36 to $28.92 per day; $9,986 to $10,556 per year.

- Of this, the out of pocket cost for me would be $2.34 to $3.90 per day; or $854 up to $1,424 per year.

- Thyroid/Graves: $0.13 per day; $48 per year

Total yearly cost:

- $27,893 (where EPI costs are 6 prescription PERT per day); 2,190 swallows

- $33,982 (where EPI costs are 8 prescription PERT per day); 2,920 swallows

- $19,615 (where EPI costs are 3 prescription PERT and 6 OTC per day); 3,285 swallows

- $20,185 (where EPI costs are 3 prescription PERT and 9 OTC per day); 4,745 swallows

* My out of pocket costs per year are $854-$1424 for EPI when using OTCs to supplement prescription PERT and an estimated $1,100 for celiac-related gluten free food costs.

** Daily cost-wise, that means $76.42, $93.10, $53.74, or $55.30 daily costs respectively.

*** The swallow “cost” is 1,095-1,825 more swallows per year to get the lower price cost of enzymes by combining prescription and OTC.

Combining these out of pocket costs with my $3,000 out of pocket max on my insurance plan, I can expect that I will therefore pay around $4,900 to $5,600 next year in health supply costs, plus another few hundred for things like tape or vitamins etc. that aren’t major expenses.

—

TLDR:

- Diabetes is expensive, and it’s not just insulin.

- Insulin is roughly 19% of my daily cost of diabetes supplies. CGM is currently 56% of my diabetes supply costs.

- EPI is super expensive.

- OTC pills can supplement prescription PERT but have reliability issues.

- However, combined with prescription PERT it can help drastically cut the price of EPI.

- The cost of this price reduction is significantly more pills to swallow on a daily basis, and adds an additional out of pocket cost that insurance doesn’t cover.

- However in my case; I am privileged enough to afford this cost and choose this over increasing everyone in my insurance plan’s costs.

- Celiac is expensive and mostly an out of pocket cost.

- Thyroid is not as expensive to manage with daily medication. Yay for one of four being reasonably priced!

REMEMBER to not use these numbers or math out of context and apply them to any other person; this is based on my usage of insulin, enzymes, etc as well as my insurance plan’s costs.

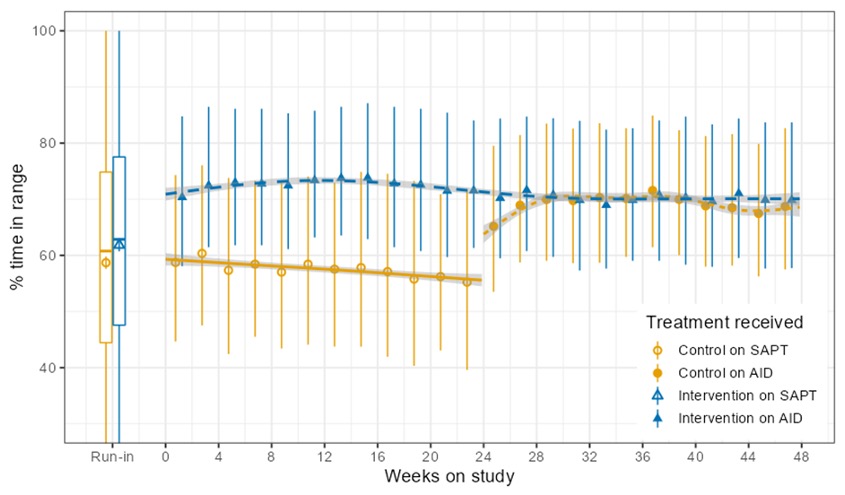

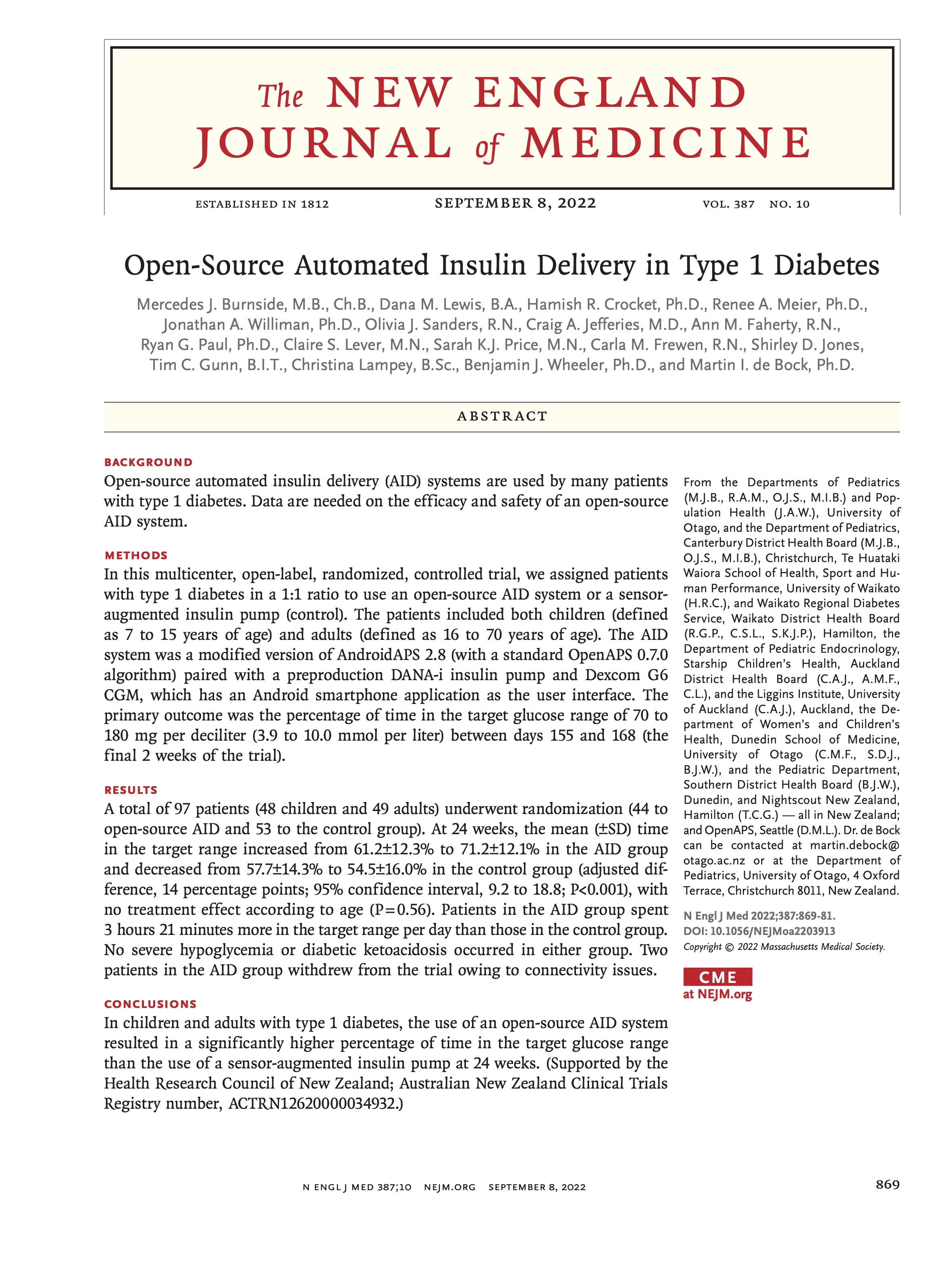

I’m thrilled to share that the results of the first RCT on open source automated insulin delivery (AID) is now published in a peer-reviewed medical journal (New England Journal of Medicine, known as NEJM). You can find it at NEJM

I’m thrilled to share that the results of the first RCT on open source automated insulin delivery (AID) is now published in a peer-reviewed medical journal (New England Journal of Medicine, known as NEJM). You can find it at NEJM

Recent Comments