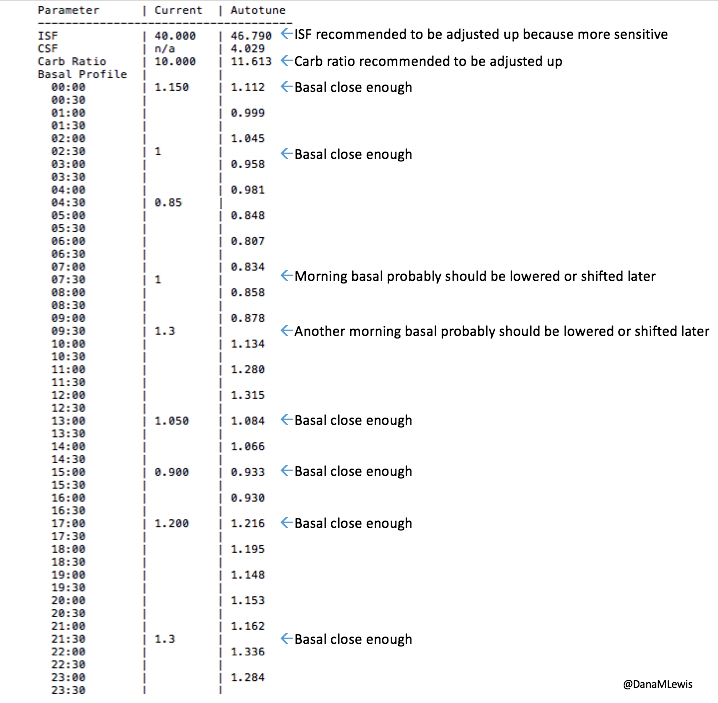

For a while, I’ve been mentioning “next-generation” algorithms in passing when talking about some of the work that Scott and I have been doing as it relates to OpenAPS development. After we created autotune to help people (even non-loopers) tune underlying pump basal rates, ISF, and CSF, we revisited one of our regular threads of conversations about how it might be possible to further reduce the burden of life with diabetes with algorithm improvements related to meal-time insulin dosing.

This is why we first created meal-assist and then “advanced meal-assist” (AMA), because we learned that most people have trouble with estimating carbs and figuring out optimal timing of meal-related insulin dosing. AMA, if enabled and informed about the number of carbs, is a stronger aid for OpenAPS users who want extra help during and following mealtimes.

Since creating AMA, Scott and I had another idea of a way that we could do even more for meal-time outcomes. Given the time constraints and reality of currently available mealtime insulins (that peak in 60-90 minutes; they’re not instantaneous), we started talking about how to leverage the idea of a “super bolus” for closed loopers.

A super bolus is an approach you can take to give more insulin up front at a meal, beyond what the carb count would call for, by “borrowing” from basal insulin that would be delivered over the next few hours. By adding insulin to the bolus and then low temping for a few hours after that, it essentially “front shifts” some of the insulin activity.

Like a lot of things done manually, it’s hard to do safely and achieve optimal outcomes. But, like a lot of things, we’ve learned that by letting computers do more precise math than we humans are wont to do, OpenAPS can actually do really well with this concept.

Introducing oref1

Those of you who are familiar with the original OpenAPS reference design know that ONLY setting temporary basal rates was a big safety constraint. Why? Because it’s less of an issue if a temporary basal rate is issued over and over again; and if the system stops communicating, the temp basal eventually expires and resume normal pump activity. That was a core part of oref0. So to distinguish this new set of algorithm features that depart from that aspect of the oref0 approach, we are introducing it as “oref1”. Most OpenAPS users will only use oref0, like they have been doing. oref1 should only be enabled specifically by any advanced users who want to test or use these features.

The notable difference between the oref0 and oref1 algorithms is that, when enabled, oref1 makes use of small “supermicroboluses” (SMB) of insulin at mealtimes to more quickly (but safely) administer the insulin required to respond to blood sugar rises due to carb absorption.

Introducing SuperMicroBoluses (or “SMB”)

The microboluses administered by oref1 are called “super” because they use a miniature version of the “super bolus” technique described above. They allow oref1 to safely dose mealtime insulin more rapidly, while at the same time setting a temp basal rate of zero of sufficient duration to ensure that BG levels will return to a safe range with no further action even if carb absorption slows suddenly (for example, due to post-meal activity or GI upset) or stops completely (for example due to an interrupted meal or a carb estimate that turns out to be too high). Where oref0 AMA might decide that 1 U of extra insulin is likely to be required, and will set a 2U/hr higher-than-normal temporary basal rate to deliver that insulin over 30 minutes, oref1 with SMB might deliver that same 1U of insulin as 0.4U, 0.3U, 0.2U, and 0.1U boluses, at 5 minute intervals, along with a 60 minute zero temp (from a normal basal of 1U/hr) in case the extra insulin proves unnecessary.

As with oref0, the oref1 algorithm continuously recalculates the insulin required every 5 minutes based on CGM data and previous dosing, which means that oref1 will continually issue new SMBs every 5 minutes, increasing or reducing their size as needed as long as CGM data indicates that blood glucose levels are rising (or not falling) relative to what would be expected from insulin alone. If BG levels start falling, there is generally already a long zero temp basal running, which means that excess IOB is quickly reduced as needed, until BG levels stabilize and more insulin is warranted.

Safety constraints and safety design for SMB and oref1

Automatically administering boluses safely is of course the key challenge with such an algorithm, as we must find another way to avoid the issues highlighted in the oref0 design constraints. In oref1, this is accomplished by using several new safety checks (as outlined here), and verifying all output, before the system can administer a SMB.

At the core of the oref1 SMB safety checks is the concept that OpenAPS must verify, via multiple redundant methods, that it knows about all insulin that has been delivered by the pump, and that the pump is not currently in the process of delivering a bolus, before it can safely do so. In addition, it must calculate the length of zero temp required to eventually bring BG levels back in range even with no further carb absorption, set that temporary basal rate if needed, and verify that the correct temporary basal rate is running for the proper duration before administering a SMB.

To verify that it knows about all recent insulin dosing and that no bolus is currently being administered, oref1 first checks the pump’s reservoir level, then performs a full query of the pump’s treatment history, calculates the required insulin dose (noting the reservoir level the pump should be at when the dose is administered) and then checks the pump’s bolusing status and reservoir level again immediately before dosing. These checks guard against dosing based on a stale recommendation that might otherwise be administered more than once, or the possibility that one OpenAPS rig might administer a bolus just as another rig is about to do so. In addition, all SMBs are limited to 1/3 of the insulin known to be required based on current information, such that even in the race condition where two rigs nearly simultaneously issue boluses, no more than 2/3 of the required insulin is delivered, and future SMBs can be adjusted to ensure that oref1 never delivers more insulin than it can safely withhold via a zero temp basal.

In some situations, a lack of BG or intermittent pump communications can prevent SMBs from being delivered promptly. In such cases, oref1 attempts to fall back to oref0 + AMA behavior and set an appropriate high temp basal. However, if it is unable to do so, manual boluses are sometimes required to finish dosing for the recently consumed meal and prevent BG from rising too high. As a result, oref1’s SMB features are only enabled as long as carb impact is still present: after a few hours (after carbs all decay), all such features are disabled, and oref1-enabled OpenAPS instances return to oref0 behavior while the user is asleep or otherwise not engaging with the system.

In addition to these safety status checks, the oref1 algorithm’s design helps ensure safety. As already noted, setting a long-duration temporary basal rate of zero while super-microbolusing provides good protection against hypoglycemia, and very strong protection against severe hypoglycemia, by ensuring that insulin delivery is zero when BG levels start to drop, even if the OpenAPS rig loses communication with the pump, and that such a suspension is long enough to eventually bring BG levels back up to the target range, even if no manual corrective action is taken (for example, during sleep). Because of these design features, oref1 may even represent an improvement over oref0 w/ AMA in terms of avoiding post-meal hypoglycemia.

In real world testing, oref1 has thus far proven at least as safe as oref0 w/ AMA with regard to hypoglycemia, and better able to prevent post-meal hyperglycemia when SMB is ongoing.

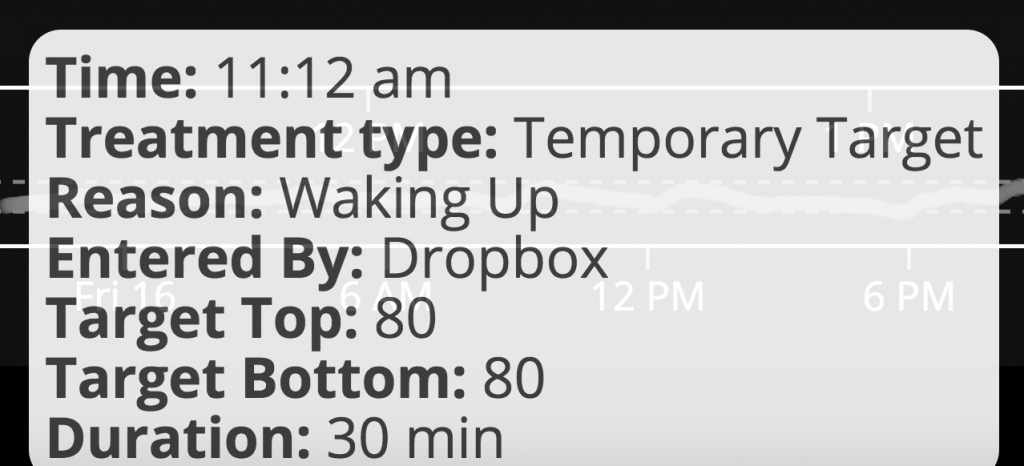

What does SMB “look” like?

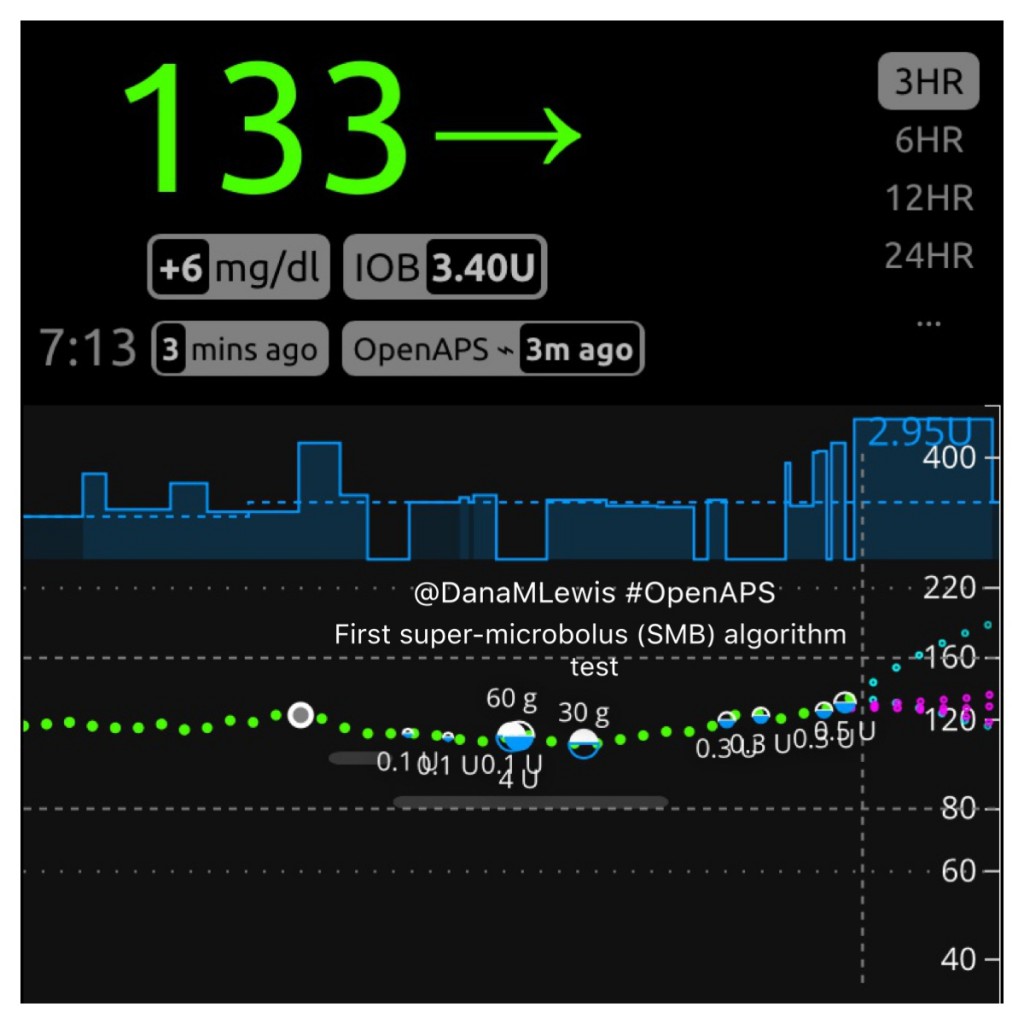

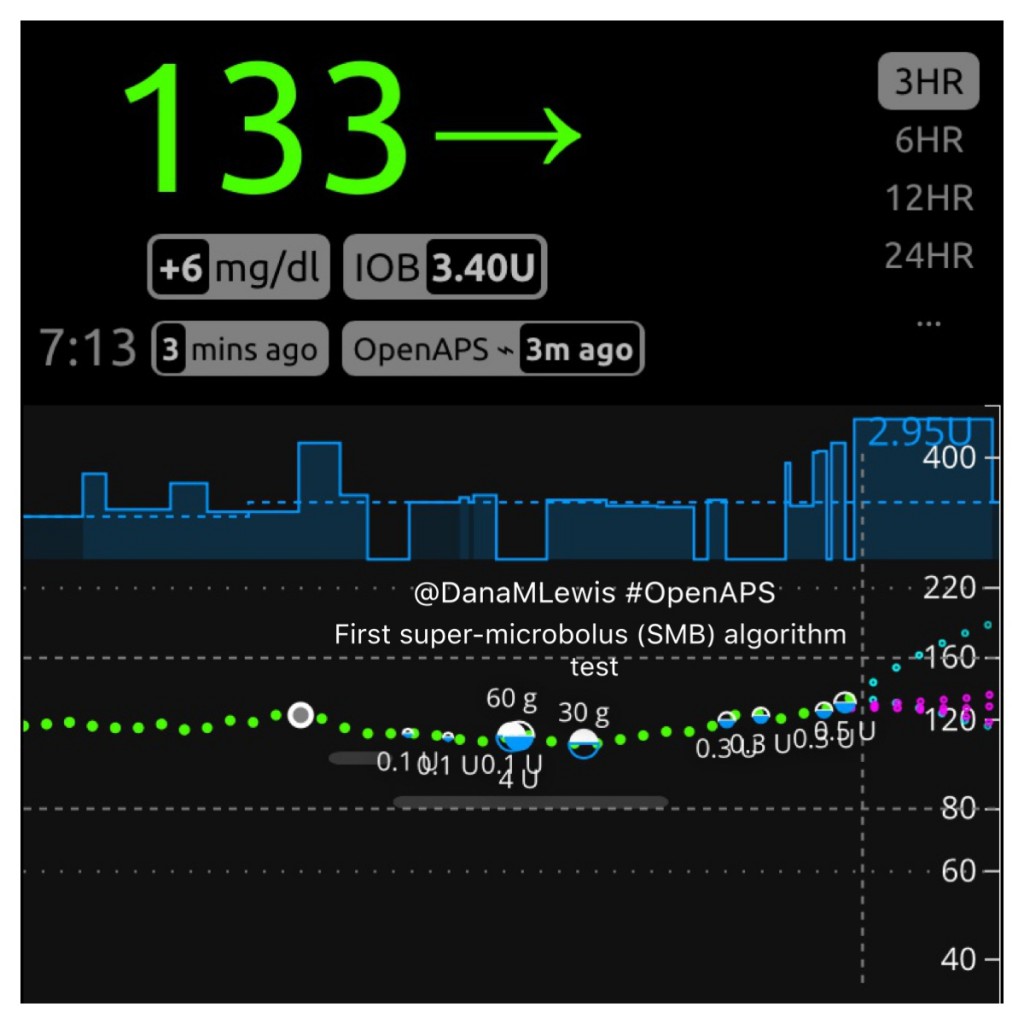

Here is what SMB activity currently looks like when displayed on Nightscout, and my Pebble watch:

How do features like this get developed and tested?

SMB, like any other advanced feature, goes through extensive testing. First, we talk about it. Then, it becomes written up in plain language as an issue for us to track discussion and development. Then we begin to develop the feature, and Scott and I test it on a spare pump and rig. When it gets to the point of being ready to test it in the real world, I test it during a time period when I can focus on observing and monitoring what it is doing. Throughout all of this, we continue to make tweaks and changes to improve what we’re developing. After several days (or for something this different, weeks) of Dana-testing, we then have a few other volunteers begin to test it on spare rigs. They follow the same process of monitoring it on spare rigs and giving feedback and helping us develop it before choosing to run it on a rig and a pump connected to their body. More feedback, discussion, and observation. Eventually, it gets to a point where it is ready to go to the “dev” branch of OpenAPS code, which is where this code is now heading. Several people will review the code and approve it to be added to the “dev” branch. We will then have others test the “dev” branch with this and any other features or code changes – both by people who want to enable this code feature, as well as people who don’t want this feature (to make sure we don’t break existing setups). Eventually, after numerous thumbs up from multiple members of the community who have helped us test different use cases, that code from the “dev” branch will be “approved” and will go to the “master” branch of code where it is available to a more typical user of OpenAPS.

However, not everyone automatically gets this code or will use it. People already running on the master branch won’t get this code or be able to use it until they update their rig. Even then, unless they were to specifically enable this feature (or any other advanced feature), they would not have this particular segment of code drive any of their rig’s behavior.

Where to find out more about oref1, SMB, etc.:

- We have updated the OpenAPS Reference Design to reflect the differences between oref0 and the oref1 features.

- OpenAPS documentation about oref1, which as of July 13, 2017 is now part of the master branch of oref0 code.

- Ask questions! Like all things developed in the OpenAPS community, SMB and oref1-related features will evolve over time. We encourage you to hop into Gitter and ask questions about these features & whether they’re right for you (if you’re DIY closed looping).

—

Special note of thanks to several people who have contributed to ongoing discussions about SMB, plus the very early testers who have been running this on spare rigs and pumps. Plus always, ongoing thanks to everyone who is contributing and has contributed to OpenAPS development!

. Saying “I am doing a thing, and it stopped working/doesn’t work” requires someone to play the game of 20 questions to draw out the above level of detail, before they can even start to answer your question of what to do next.

. Saying “I am doing a thing, and it stopped working/doesn’t work” requires someone to play the game of 20 questions to draw out the above level of detail, before they can even start to answer your question of what to do next.

Recent Comments