“I could never do that,” you say.

And I’ve heard it before.

Eating gluten free for the rest of your life, because you were diagnosed with celiac disease? Heard that response (I could never do that) for going on 14 years.

Inject yourself with insulin or fingerstick test your blood glucose 14 times a day? Wear an insulin pump on your body 24/7/365? Wear a CGM on your body 24/7/365?

Yeah, I’ve heard you can’t do that, either. (For 20 years and counting.) Which means I and the other people living with the situations that necessitate these behaviors are…doing this for fun?

We’re not.

More recently, I’ve heard this type of comment come up about tracking what I’m eating, and in particular, tracking what I’m eating when I’m running. I definitely don’t do that for fun.

—

I have a 20+ year strong history of hating tracking things, actually. When I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, I was given a physical log book and asked to write down my blood glucose numbers.

“Why?” I asked. They’re stored in the meter.

The answer was because supposedly the medical team was going to review them.

And they did.

And it was useless.

“Why were you high on February 22, 2003?”

Whether we were asking this question in March of 2003 or January of 2023 (almost 20 years later), the answer would be the same: I have no idea.

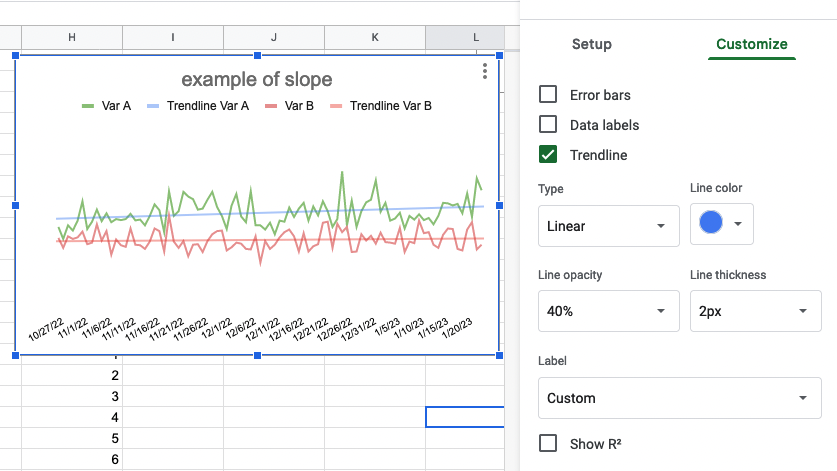

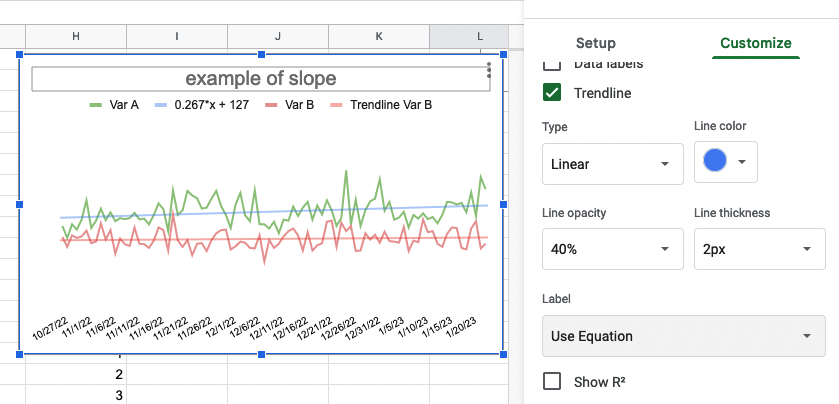

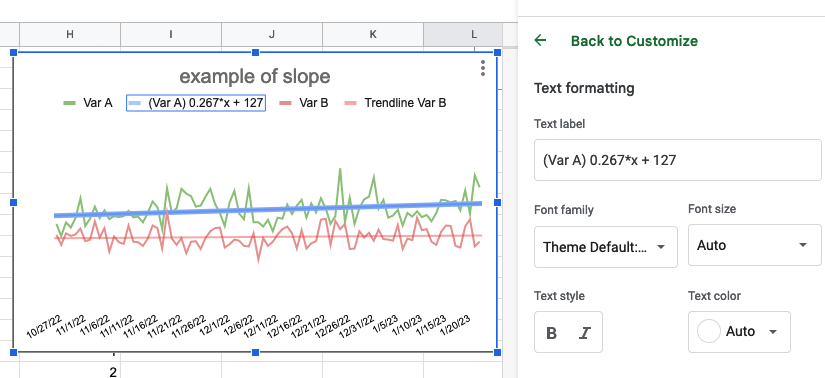

BG data, by itself, is like a single data point for a pilot. It’s useless without the contextual stream of data as well as other metrics (in the diabetes case, things like what was eaten, what activity happened, what my schedule was before this point, and all insulin dosed potentially in the last 12-24h).

So you wouldn’t be surprised to find out that I stopped tracking. I didn’t stop testing my blood glucose levels – in fact, I tested upwards of 14 times a day when I was in high school, because the real-time information was helpful. Retrospectively? Nope.

—

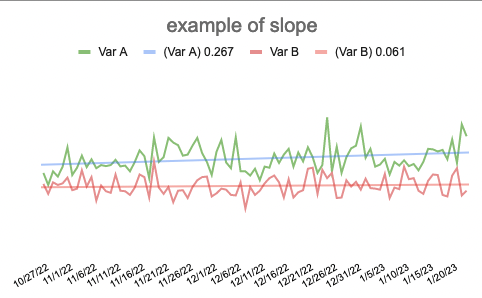

I didn’t start “tracking” things again (for diabetes) until late 2013, when we realized that I could get my CGM data off the device and into the laptop beside my bed, dragging the CGM data into a CSV file in Dropbox and sending it to the cloud so an app called “Pushover” would make a louder and different alarm on my phone to wake me up to overnight hypoglycemia. The only reason I added any manual “tracking” to this system was because we realized we could create an algorithm to USE the information I gave it (about what I was eating and the insulin I was taking) combined with the real-time CGM data to usefully predict glucose levels in the future. Predictions meant we could make *predictive* alarms, instead of solely having *reactive* alarms, which is what the status quo in diabetes has been for decades.

So sure, I started tracking what I was eating and dosing, but not really. I was hitting buttons to enter this information into the system because it was useful, again, in real time. I didn’t bother doing much with the data retrospectively. I did occasional do things like reflect on my changes in sensitivity after I got the norovirus, for example, but again this was mostly looking in awe at how the real-time functionality of autosensitivity, an algorithm feature we designed to adjust to real-time changes in sensitivity to insulin, dealt throughout the course of being sick.

—

At the beginning of 2020, my life changed. Not because of the pandemic (although also because of that), but because I began to have serious, very bothersome GI symptoms that dragged on throughout 2020 and 2021. I’ve written here about my experiences in eventually self-diagnosing (and confirming) that I have exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and began taking pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in January 2022.

What I haven’t yet done, though, is explain all my failed attempts at tracking things in 2020 and 2021. Or, not failed attempts, but where I started and stopped and why those tracking attempts weren’t useful.

Once I realized I had GI symptoms that weren’t going away, I tried writing down everything I ate. I tried writing in a list on my phone in spring of 2020. I couldn’t see any patterns. So I stopped.

A few months later, in summer of 2020, I tried again, this time using a digital spreadsheet so I could enter data from my phone or my computer. Again, after a few days, I still couldn’t see any patterns. So I stopped.

I made a third attempt to try to look at ingredients, rather than categories of food or individual food items. I came up with a short list of potential contenders, but repeated testing of consuming those ingredients didn’t do me any good. I stopped, again.

When I first went to the GI doctor in fall of 2020, one of the questions he asked was whether there was any pattern between my symptoms and what I was eating. “No,” I breathed out in a frustrated sigh. “I can’t find any patterns in what I’m eating and the symptoms.”

So we didn’t go down that rabbit hole.

At the start of 2021, though, I was sick and tired (of being sick and tired with GI symptoms for going on a year) and tried again. I decided that some of my “worst” symptoms happened after I consumed onions, so I tried removing obvious sources of onion from my diet. That evolved to onion and garlic, but I realized almost everything I ate also had onion powder or garlic powder, so I tried avoiding those. It helped, some. That then led me to research more, learn about the categorization of FODMAPs, and try a low-FODMAP diet in mid/fall 2021. That helped some.

Then I found out I actually had exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and it all made sense: what my symptoms were, why they were happening, and why the numerous previous tracking attempts were not successful.

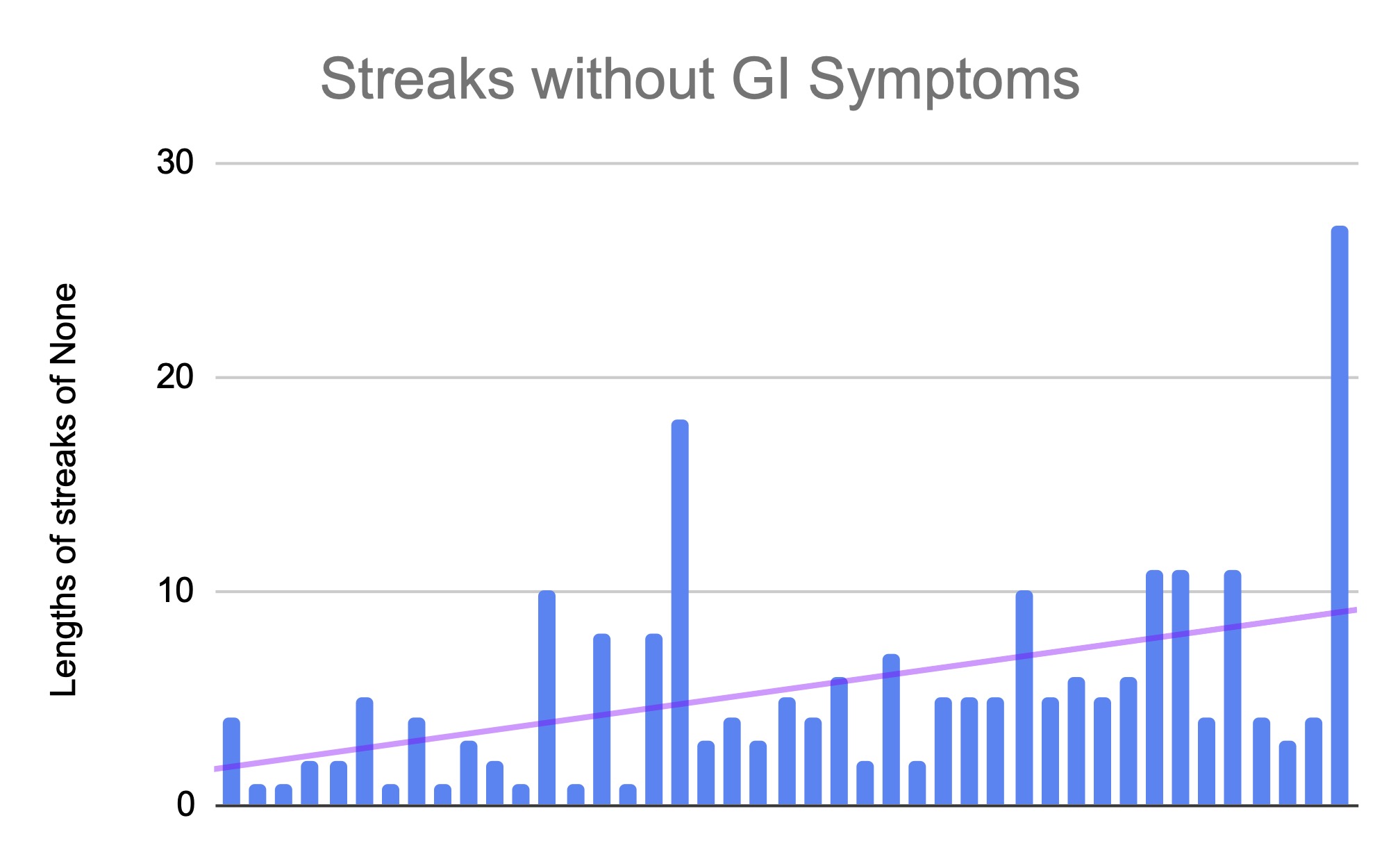

You wouldn’t think I’d start tracking again, but I did. Although this time, finally, was different.

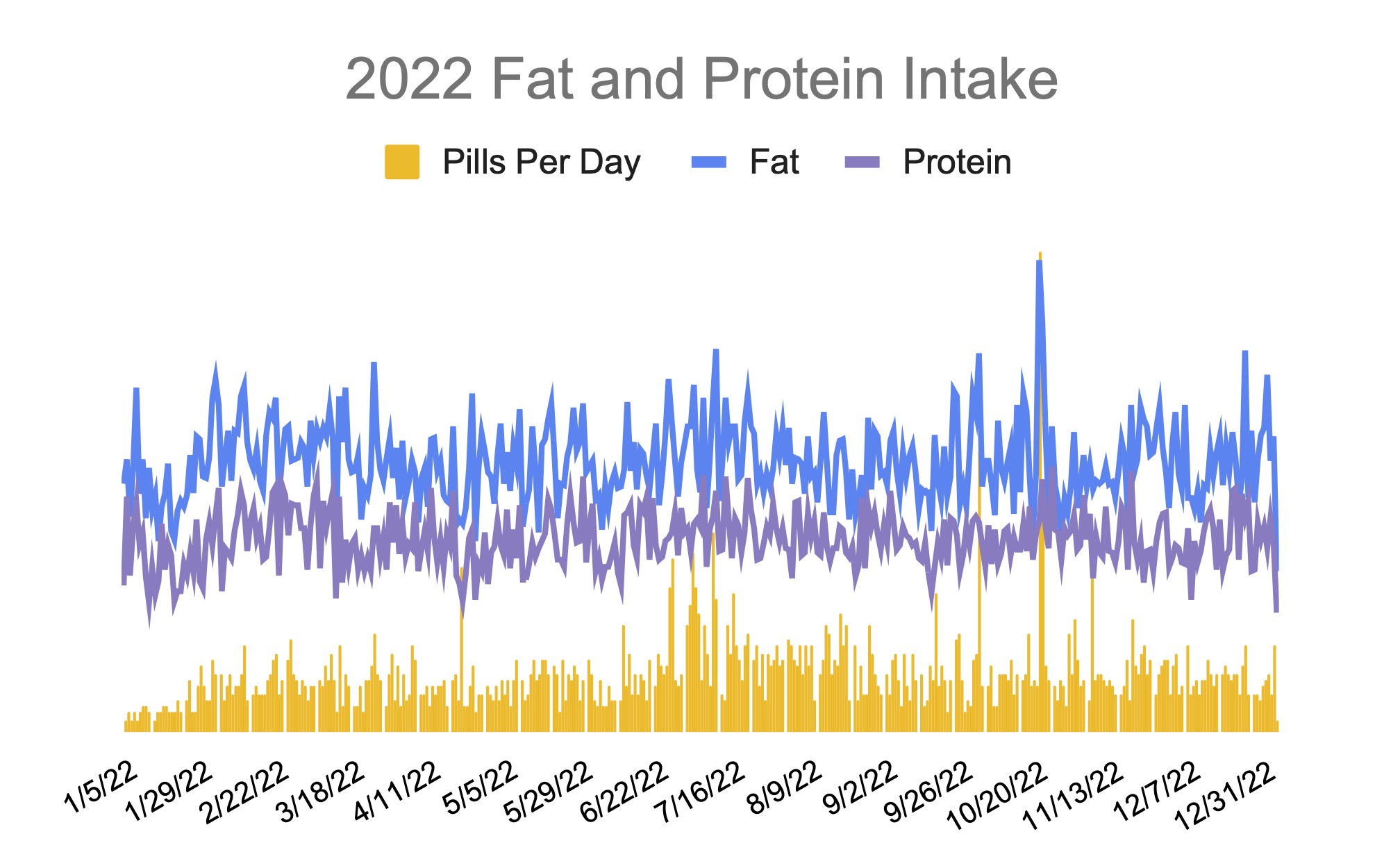

When I realized I had EPI, I learned that my body was no longer producing enough digestive enzymes to help my body digest fat, protein, and carbs. Because I’m a person with type 1 diabetes and have been correlating my insulin doses to my carbohydrate consumption for 20+ years, it seemed logical to me to track the amount of fat and protein in what I was eating, track my enzyme (PERT) dosing, and see if there were any correlations that indicated my doses needed to be more or less.

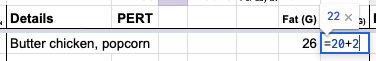

My spreadsheet involved recording the outcome of the previous day’s symptoms, and I had a section for entering multiple things that I ate throughout the day and the number of enzymes. I wrote a short description of my meal (“butter chicken” or “frozen pizza” or “chicken nuggets and veggies”), the estimate of fat and protein counts for the meal, and the number of enzymes I took for that meal. I had columns on the left that added up the total amount of fat and protein for the day, and the total number of enzymes.

It became very apparent to me – within two days – that the dose of the enzymes relative to the quantity of fat and protein I was eating mattered. I used this information to titrate (adjust) my enzyme dose and better match the enzymes to the amount of fat or protein I was eating. It was successful.

I kept writing down what I was eating, though.

In part, because it became a quick reference library to find the “counts” of a previous meal that I was duplicating, without having to re-do the burdensome math of adding up all the ingredients and counting them out for a typical portion size.

It also helped me see that within the first month, I was definitely improving, but not all the way – in terms of fully reducing and eliminating all of my symptoms. So I continued to use it to titrate my enzyme doses.

Then it helped me carefully work my way through re-adding food items and ingredients that I had been avoiding (like onions, apples, and pears) and proving to my brain that those were the result of enzyme insufficiency, not food intolerances. Once I had a working system for determining how to dose enzymes, it became a lot easier to see when I had slight symptoms from slightly getting my dosing wrong or majorly mis-estimating the fat and protein in what I was eating.

It provided me with a feedback loop that doesn’t really exist in EPI and GI conditions, and it was a daily, informative, real-time feedback loop.

As I reached the end of my first year of dosing with PERT, though, I was still using my spreadsheet. It surprised me, actually. Did I need to be using it? Not all the time. But the biggest reason I kept using it relates to how I often eat. I often look at an ‘entree’ for protein and then ‘build’ the rest of my meal around that, to help make sure I’m getting enough protein to fuel my ultrarunning endeavors. So I pick my entree/main thing I’m eating and put it in my spreadsheet under the fat and protein columns (=17 g of fat, =20 g of protein), for example, then decide what I’m going to eat to go with it. Say I add a bag of cheddar popcorn, so that becomes (=17+9 g of fat) and (=20+2 g of protein), and when I hit enter, those cells now tell me it’s 26 g of fat and 22 g of protein for the meal, which tells my brain (and I also tell the spreadsheet) that I’ll take 1 PERT pill for that. So I use the spreadsheet functionally to “build” what I’m eating and calculate the total grams of protein and fat; which helps me ‘calculate’ how much PERT to take (based on my previous titration efforts I know I can do up to 30g of fat and protein each in one PERT pill of the size of my prescription)

Essentially, this has become a real-time calculator to add up the numbers every time I eat. Sure, I could do this in my head, but I’m usually multitasking and deciding what I want to eat and writing it down, doing something else, doing yet something else, then going to make my food and eat it. This helps me remember, between the time I decided – sometimes minutes, sometimes hours in advance of when I start eating and need to actually take the enzymes – what the counts are and what the PERT dosing needs to be.

I have done some neat retrospective analysis, of course – last year I had estimated that I took thousands of PERT pills (more on that here). I was able to do that not because it’s “fun” to track every pill that I swallow, but because I had, as a result of functional self-tracking of what I was eating to determine my PERT dosing for everything I ate, had a record of 99% of the enzyme pills that I took last year.

I do have some things that I’m no longer entering in my spreadsheet, which is why it’s only 99% of what I eat. There are some things like a quick snack where I grab it and the OTC enzymes to match without thought, and swallow the pills and eat the snack and don’t write it down. That maybe happens once a week. Generally, though, if I’m eating multiple things (like for a meal), then it’s incredibly useful in that moment to use my spreadsheet to add up all the counts to get my dosing right. If I don’t do that, my dosing is often off, and even a little bit “off” can cause uncomfortable and annoying symptoms the rest of the day, overnight, and into the next morning.

So, I have quite the incentive to use this spreadsheet to make sure that I get my dosing right. It’s functional: not for the perceived “fun” of writing things down.

–

It’s the same thing that happens when I run long runs. I need to fuel my runs, and fuel (food) means enzymes. Figuring out how many enzymes to dose as I’m running 6, 9, or 25 hours into a run gets increasingly harder. I found that what works for me is having a pre-built list of the fuel options; and a spreadsheet where I quickly on my phone open it and tap a drop down list to mark what I’m eating, and it pulls in the counts from the library and tells me how many enzymes to take for that fuel (which I’ve already pre-calculated).

It’s useful in real-time for helping me dose the right amount of enzymes for the fuel that I need and am taking every 30 minutes throughout my run. It’s also useful for helping me stay on top of my goal amounts of calories and sodium to make sure I’m fueling enough of the right things (for running in general), which is something that can be hard to do the longer I run. (More about this method and a template for anyone who wants to track similarly here.)

–

The TL;DR point of this is: I don’t track things for fun. I track things if and when they’re functionally useful, and primarily that is in real-time medical decision making.

These methods may not make sense to you, and don’t have to.

It may not be a method that works for you, or you may not have the situation that I’m in (T1D, Graves, celiac, and EPI – fun!) that necessitates these, or you may not have the goals that I have (ultrarunning). That’s ok!

But don’t say that you “couldn’t” do something. You ‘couldn’t’ track what you consumed when you ran or you ‘couldn’t’ write down what you were eating or you ‘couldn’t’ take that many pills or you ‘couldn’t’ inject insulin or…

You could, if you needed to, and if you decided it was the way that you could and would be able to achieve your goals.

)

)

Recent Comments