What if, instead of guessing needed changes (the current most used method) basal rates, ISF, and carb ratios…we could use data to empirically determine how these ratios should be adjusted?

Meet autotune.

Historically, most people have guessed basal rates, ISF, and carb ratios. Their doctors may use things like the “rule of 1500” or “1800” or body weight. But, that’s all a general starting place. Over time, people have to manually tweak these underlying basals and ratios in order to best live life with type 1 diabetes. It’s hard to do this manually, and know if you’re overcompensating with meal boluses (aka an incorrect carb ratio) for basal, or over-basaling to compensate for meal times or an incorrect ISF.

And why do these values matter?

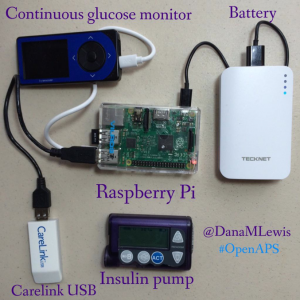

It’s not just about manually dosing with this information. But importantly, for most DIY closed loops (like #OpenAPS), dose adjustments are made based on the underlying basals, ISF, and carb ratio. For someone with reasonably tuned basals and ratios, that’s works great. But for someone with values that are way off, it means the system can’t help them adjust as much as someone with well-tuned values. It’ll still help, but it’ll be a fraction as powerful as it could be for that person.

There wasn’t much we could do about that…at first. We designed OpenAPS to fall back to whatever values people had in their pumps, because that’s what the person/their doctor had decided was best. However, we know some people’s aren’t that great, for a variety of reasons. (Growth, activity changes, hormonal cycles, diet and lifestyle changes – to name a few. Aka, life.)

With autosensitivity, we were able to start to assess when actual BG deltas were off compared to what the system predicted should be happening. And with that assessment, it would dynamically adjust ISF, basals, and targets to adjust. However, a common reaction was people seeing the autosens result (based on 24 hours data) and assume that mean that their underlying ISF/basal should be changed. But that’s not the case for two reasons. First, a 24 hour period shouldn’t be what determines those changes. Second, with autosens we cannot tell apart the effects of basals vs. the effect of ISF.

Autotune, by contrast, is designed to iteratively adjust basals, ISF, and carb ratio over the course of weeks – based on a longer stretch of data. Because it makes changes more slowly than autosens, autotune ends up drawing on a larger pool of data, and is therefore able to differentiate whether and how basals and/or ISF need to be adjusted, and also whether carb ratio needs to be changed. Whereas we don’t recommend changing basals or ISF based on the output of autosens (because it’s only looking at 24h of data, and can’t tell apart the effects of basals vs. the effect of ISF), autotune is intended to be used to help guide basal, ISF, and carb ratio changes because it’s tracking trends over a large period of time.

Ideally, for those of us using DIY closed loops like OpenAPS, you can run autotune iteratively inside the closed loop, and let it tune basals, ISF, and carb ratio nightly and use those updated settings automatically. Like autosens, and everything else in OpenAPS, there are safety caps. Therefore, none of these parameters can be tuned beyond 20-30% from the underlying pump values. If someone’s autotune keeps recommending the maximum (20% more resistant, or 30% more sensitive) change over time, then it’s worth a conversation with their doctor about whether your underlying values need changing on the pump – and the person can take this report in to start the discussion.

Not everyone will want to let it run iteratively, though – not to mention, we want it to be useful to anyone, regardless of which DIY closed loop they choose to use – or not! Ideally, this can be run one-off by anyone with Nightscout data of BG and insulin treatments. (Note – I wrote this blog post on a Friday night saying “There’s still some more work that needs to be done to make it easier to run as a one-off (and test it with people who aren’t looping but have the right data)…but this is the goal of autotune!” And as by Saturday morning, we had volunteers who sat down with us and within 1-2 hours had it figured out and documented! True #WeAreNotWaiting. :))

And from what we know, this may be the first tool to help actually make data-driven recommendations on how to change basal rates, ISF, and carb ratios.

How autotune works:

Step 1: Autotune-prep

- Autotune-prep takes three things initially: glucose data; treatments data; and starting profile (originally from pump; afterwards autotune will set a profile)

- It calculates BGI and deviation for each glucose value based on treatments

- Then, it categorizes each glucose value as attributable to either carb sensitivity factor (CSF), ISF, or basals

- To determine if a “datum” is attributable to CSF, carbs on board (COB) are calculated and decayed over time based on observed BGI deviations, using the same algorithm used by Advanced Meal Asssit. Glucose values after carb entry are attributed to CSF until COB = 0 and BGI deviation <= 0. Subsequent data is attributed as ISF or basals.

- If BGI is positive (meaning insulin activity is negative), BGI is smaller than 1/4 of basal BGI, or average delta is positive, that data is attributed to basals.

- Otherwise, the data is attributed to ISF.

- All this data is output to a single file with 3 sections: ISF, CSF, and basals.

Step 2: Autotune-core

- Autotune-core reads the prepped glucose file with 3 sections. It calculates what adjustments should be made to ISF, CSF, and basals accordingly.

- For basals, it divides the day into hour long increments. It calculates the total deviations for that hour increment and calculates what change in basal would be required to adjust those deviations to 0. It then applies 20% of that change needed to the three hours prior (because of insulin impact time). If increasing basal, it increases each of the 3 hour increments by the same amount. If decreasing basal, it does so proportionally, so the biggest basal is reduced the most.

- For ISF, it calculates the 50th percentile deviation for the entire day and determines how much ISF would need to change to get that deviation to 0. It applies 10% of that as an adjustment to ISF.

- For CSF, it calculates the total deviations over all of the day’s mealtimes and compares to the deviations that are expected based on existing CSF and the known amount of carbs entered, and applies 10% of that adjustment to CSF.

- Autotune applies a 20% limit on how much a given basal, or ISF or CSF, can vary from what is in the existing pump profile, so that if it’s running as part of your loop, autotune can’t get too far off without a chance for a human to review the changes.

(See more about how to run autotune here in the OpenAPS docs.)

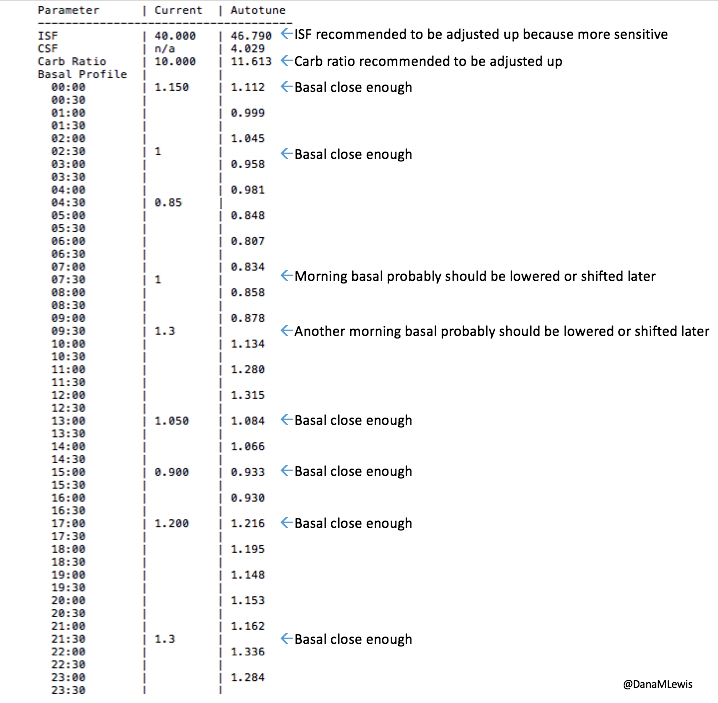

What autotune output looks like:

Here’s an example of autotune output.

Autotune is one of the things Scott and I spent time on over the holidays (and hinted about at the end of my development review of 2016 for OpenAPS). As always with #OpenAPS, it’s awesome to take an idea, get it coded up, get it tested with some early adopters/other developers within days, and continue to improve it!

A big thank you to those who’ve been testing and helping iterate on autotune (and of course, all other things OpenAPS). It’s currently in the dev branch of oref0 for anyone who wants to try it out, either one-off or for part of their dev loop. Documentation is currently here, and this is the issue in Github for logging feedback/input, along with sharing and asking questions as always in Gitter!

There are some

There are some

Recent Comments