As I mentioned, I am honored to have two presentations and a co-authored poster being presented at #2018ADA. As per my usual, I plan to post all content and make it fully available online as the embargo lifts. There will be three sets of content:

As I mentioned, I am honored to have two presentations and a co-authored poster being presented at #2018ADA. As per my usual, I plan to post all content and make it fully available online as the embargo lifts. There will be three sets of content:

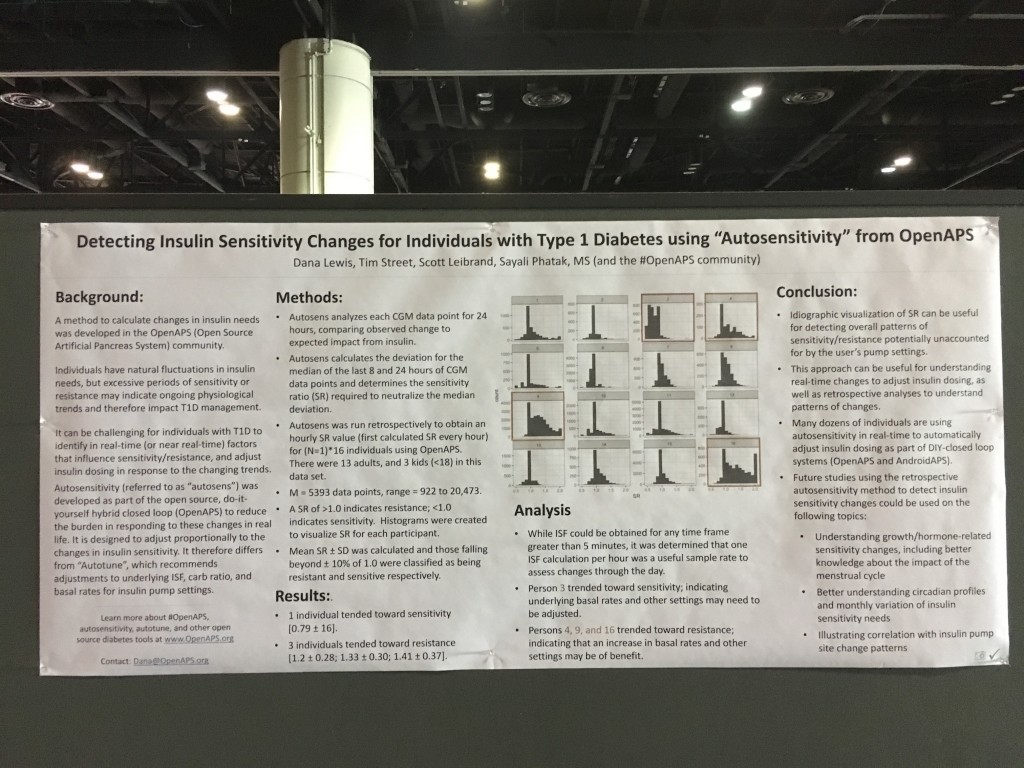

- Poster 79-LB in Category 12-A ‘Detecting Insulin Sensitivity Changes for Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes using “Autosensitivity” from OpenAPS’ poster, co-authored by Dana Lewis, Tim Street, Scott Leibrand, and Sayali Phatak.

- Content from my presentation Saturday, ‘The Data behind DIY Diabetes—Opportunities for Collaboration and Ongoing Research’, which is part of the “The Diabetes Do-It-Yourself (DIY) Revolution” Symposium!

- Content from my presentation Monday, ‘Improvements in A1c and Time-in-Range in DIY Closed-Loop (OpenAPS) Users’, co-authored by Dana Lewis, Scott Swain, and Tom Donner.

First up: the autosensitivity poster!

You can find the full write up and content of the autosensitivity poster in a post over on OpenAPS.org. There’s also a twitter thread if you’d like to share this poster with others on Twitter or elsewhere.

You can find the full write up and content of the autosensitivity poster in a post over on OpenAPS.org. There’s also a twitter thread if you’d like to share this poster with others on Twitter or elsewhere.

Summary: we ran autosensitivity retrospectively on the command line to assess patterns of sensitivity changes for 16 individuals who had donated data in the OpenAPS Data Commons. Many had normal distributions of sensitivity, but we found a few people who trended sensitive or resistant, indicating underlying pump settings could likely benefit from a change.

Presentation:

‘The Data behind DIY Diabetes—Opportunities for Collaboration and Ongoing Research’

This presentation was a big deal to me, as it was flanked by 3 other excellent presentations on the topic of DIY and diabetes. Jason Wittmer gave a great overview and context setting of DIY diabetes, ranging from DIY remote monitoring and CGM tools all the way to DIY closed loops like OpenAPS. Jason is a dad who created OpenAPS rigs for his son with T1D. Lorenzo Sandini spoke about the clinician’s perspective for when patients come into the office with DIY tools. He knows it from both sides – he’s using OpenAPS rigs, and also has patients who use OpenAPS. And after my presentation, Joyce Lee also spoke about the overarching landscape of diabetes and the role DIY plays in this emerging technology space.

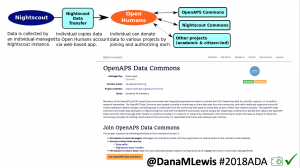

Why did I present as part of this group today? One of the roles I’ve taken on in the last few years in the OpenAPS community (among others) is a collaborator and facilitator of research with and about the community. I put together the first outcomes study (see here in JDST or here in a blog post form on OpenAPS.org) in 2016. We presented a poster on Autotune last year at ADA (see here in a blog post form on OpenAPS.org). I’ve also worked to create and manage the OpenAPS Data Commons, as well as build tools for researchers to use this data, so individuals can easily and anonymously donate their DIY closed loop data for other research projects, lowering the friction and barriers for both patients and researchers. And, I’ve co-led or led several research projects with the community’s data as a result.

My presentation was therefore about setting the stage with background on OpenAPS & how we ended up creating the OpenAPS Data Commons; presenting a selection of research projects that have utilized data from the community; highlighting other research projects working with the OpenAPS community; announcing a new international collaboration (OPEN – more coming on that in the future!) for research with the DIY community; and hopefully encouraging other diabetes researchers to think about sharing their work, data, methods, tools, and insights as openly possible to help us all move forward with improving the lives of people with diabetes.

That is, of course, quite an abbreviated summary! I’ve shared a thread on Twitter that goes into detail on each of the key points as part of the presentation, or there’s a version of this Twitter/presentation content also written below.

If you’re someone who wants to do research with retrospective data from the OpenAPS Data Commons, you can find out more about it here (including instructions on how to request data). And if you’re interested in prospective research, please do reach out as well!

Full content for those who don’t want to read Twitter:

Patients are often seen as passive recipients of care, but many of us PWDs have discovered that problems are opportunities to change things. My journey to DIY began after I was frustrated by my inability to hear CGM alarms at night. 4 years ago, there was no way for me to access my own device data in real time OR retrospectively. Thanks to John Costik for sharing his code, I was able to get my CGM data & send it to the cloud and down to my phone, creating a louder alarm. Scott and I created an algorithm to push notifications to me to take action. This was an ‘open loop’ system we called #DIYPS. With Ben West’s help, we realized could combine our algorithm with small, off-the-shelf hardware & a radio stick to automate insulin delivery. #OpenAPS was thus created, open sourcing all components of DIY closed loop system so others could close the loop, too. An #OpenAPS rig consists of a small computer, radio chip, & battery. The hardware is constantly evolving. Many of us also use Nightscout to visualize our closed loop data, and share with loved ones.

I closed the loop in December of 2015. As people learned about it, I got pushback: “It works for you, but how do you know it’s going to work for others?” I didn’t, and I said so. But that didn’t mean I shouldn’t share what was working for me.

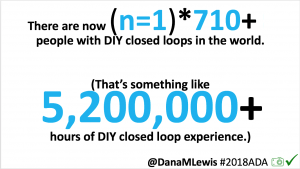

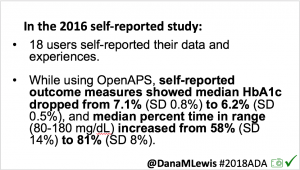

Once we had dozens of users of #OpenAPS, we presented a research study at #2016ADA, with 18 individuals sharing outcomes data on A1c, TIR, and QOL improvements. (See that publication here: https://twitter.com/danamlewis/status/763782789070192640 ). I was often asked to share my data for people to analyze, but I’m not representative of entire #OpenAPS community. Plus, the community has kept growing: we estimate there are more than (n=1)*710+ (as of June 2018) people worldwide using different kinds of DIY APs. (Note: if you’d like to keep track of the growing #OpenAPS community, the count of loopers worldwide is updated periodically at https://openaps.org/outcomes ). I began to work with Open Humans to build the #OpenAPS Data Commons, enabling individuals to anonymously upload their data and consent to share it with the Data Commons.

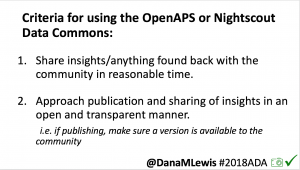

Criteria for using the #OpenAPS Data Commons:

- 1) share insights back with the community, especially if you find something about an individual’s data set where we should notify them

- 2) publish in an accessible (and preferably open) manner

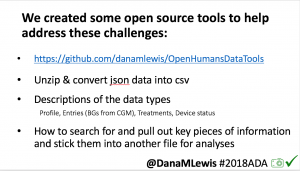

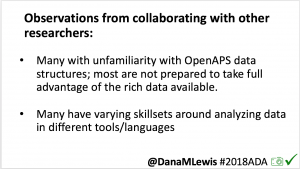

I’ve learned that not many are prepared to take advantage of the rich (and complex) data available from #OpenAPS users; and many researchers have varying background and skillsets. To aid researchers, I created a series of open source tools (described here: http://bit.ly/2l5ypxq, and tools available at https://github.com/danamlewis/OpenHumansDataTools ) to help researchers & patients working with data.

We have a variety of research projects that have leveraged the anonymously donated, DIY closed loop data from the #OpenAPS Data Commons.

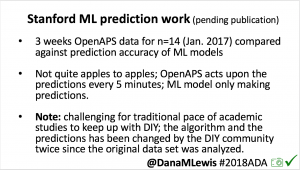

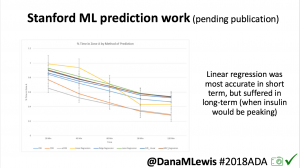

One research project, in collaboration with a Stanford team, evaluated published machine learning model predictions & #OpenAPS predictions. Some models (particularly linear regression) = accurate predictions in short term, but less so longer term when insulin peaks. This study is pending publication, but I’d like to note the challenge of more traditional research keeping pace with DIY innovation: the code (and data) studied was from January 2017. #OpenAPS prediction code has been updated 2x since then.

One research project, in collaboration with a Stanford team, evaluated published machine learning model predictions & #OpenAPS predictions. Some models (particularly linear regression) = accurate predictions in short term, but less so longer term when insulin peaks. This study is pending publication, but I’d like to note the challenge of more traditional research keeping pace with DIY innovation: the code (and data) studied was from January 2017. #OpenAPS prediction code has been updated 2x since then.- In response to the feedback from the #2016ADA #OpenAPS Outcomes study we presented, a follow up study on #OpenAPS outcomes was created in partnership with a team at Johns Hopkins. That study will be presented on Monday, 6-6:15pm (352-OR).

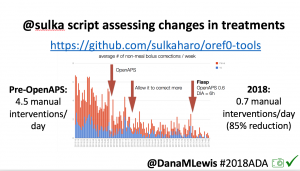

Many people share publicly online their outcomes with DIY closed loops. Sulka Haro has shared his script to evaluate the reduction in daily manual diabetes interventions after they began using #OpenAPS. Before: 4.5/day manual corrections; now they treat <1/day.

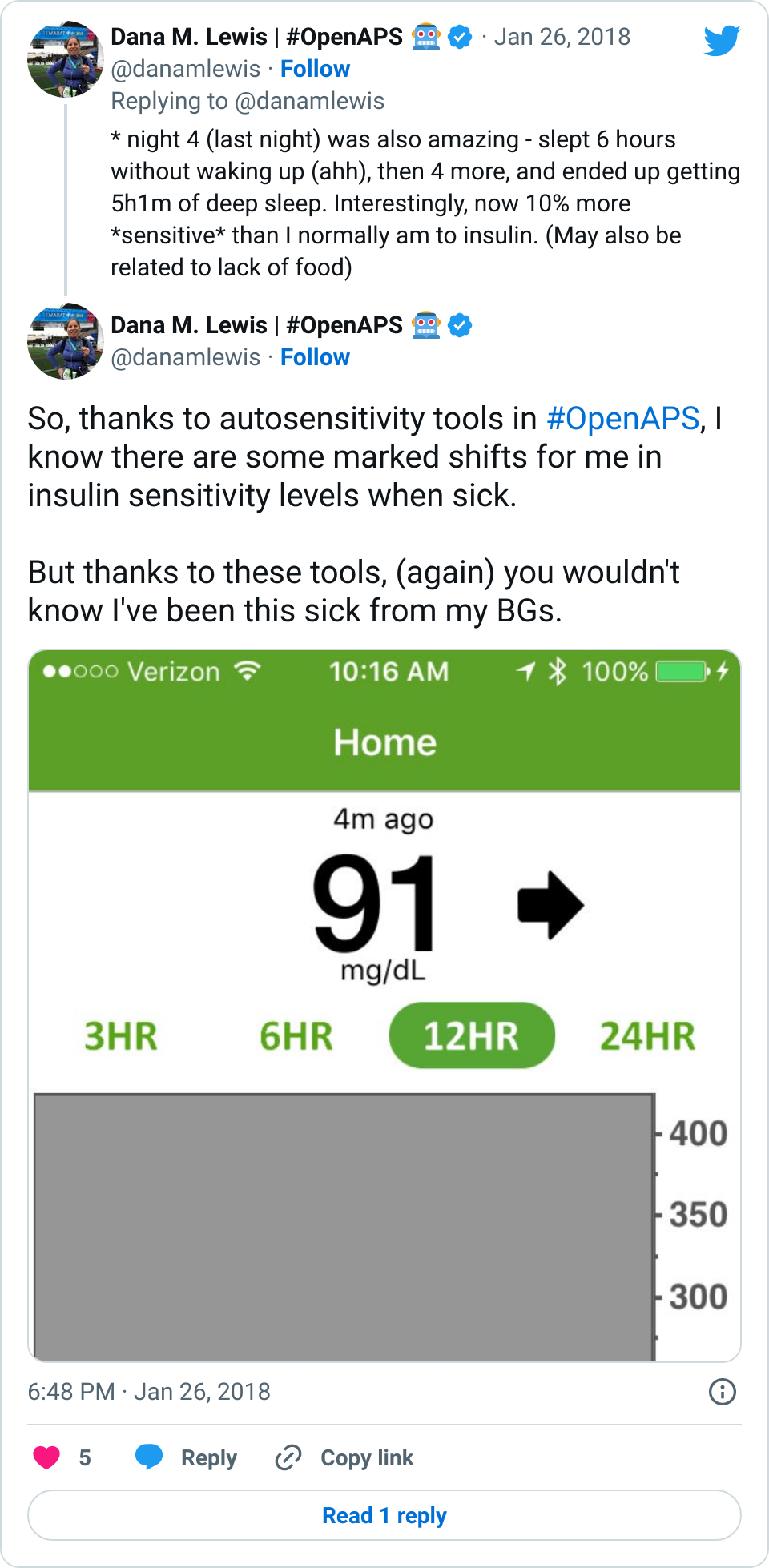

Many people share publicly online their outcomes with DIY closed loops. Sulka Haro has shared his script to evaluate the reduction in daily manual diabetes interventions after they began using #OpenAPS. Before: 4.5/day manual corrections; now they treat <1/day.- #OpenAPS features such as autosensitivity automatically detect sensitivity changes and insulin needs, improving outcomes. (See above at the top of this post for the full poster content).

- If you missed it at #2017ADA (see here: http://bit.ly/2rMBFmn) , Autotune is a tool for assessing changes to basal rates, ISF, and carb ratio. Developed for #OpenAPS users but can also be used by traditional pumpers (and some MDI users also utilize it).

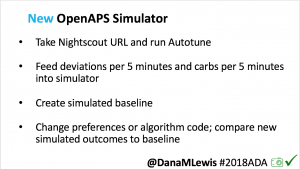

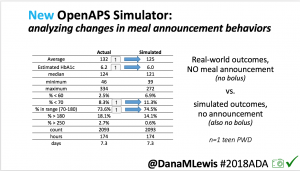

I’m also thrilled to share a new tool we’ve created: an #OpenAPS simulator to allow us to more easily back-test and compare settings changes & feature changes in #OpenAPS code.

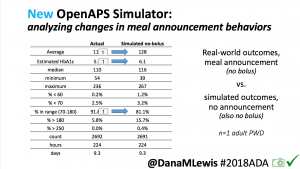

We pulled a recent week of data for n=1 adult PWD who does no-bolus, rough carb entry meal announcements, and ran the simulator to predict what the outcomes would be for no-bolus and no meal-announcement.

We pulled a recent week of data for n=1 adult PWD who does no-bolus, rough carb entry meal announcements, and ran the simulator to predict what the outcomes would be for no-bolus and no meal-announcement.

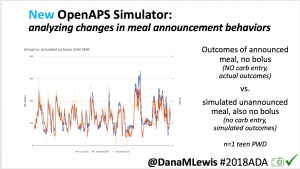

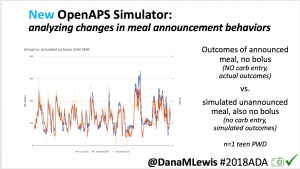

We also ran the simulator on n=1 teen PWD who does no-bolus and no-meal-announcement in real life. The simulator tracked closely to his actual outcomes (validated this week with a lab-A1c of 6.1)

We also ran the simulator on n=1 teen PWD who does no-bolus and no-meal-announcement in real life. The simulator tracked closely to his actual outcomes (validated this week with a lab-A1c of 6.1)

The new #OpenAPS simulator will allow us to better test future algorithm changes and features across a diverse data set donated by DIY closed loop users.

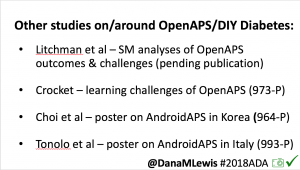

There are many other studies & collaborations ongoing with the DIY community.

- Michelle Litchman, Perry Gee, Lesly Kelly, and myself have a paper pending review analyzing social-media-reported outcomes & themes from DIY community.

There are also multiple other posters about DIY outcomes here at #2018ADA:

There are also multiple other posters about DIY outcomes here at #2018ADA:

- See 983-P on learning curves in DIY AP (Crocket);

- 964-P on real-world outcomes from Korea (Choi et al);

- and 993-P on #OpenAPS outcomes in Italy (Tonolo et al).

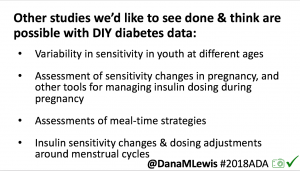

There are many topics of interest in DIY community we’d like to see studies on, and have data for. These include: “eating soon” (optimal insulin dosing for lesser post-prandial spikes); and variability in sensitivity for various ages, pregnancy, and menstrual cycle.

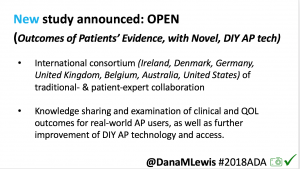

There are many topics of interest in DIY community we’d like to see studies on, and have data for. These include: “eating soon” (optimal insulin dosing for lesser post-prandial spikes); and variability in sensitivity for various ages, pregnancy, and menstrual cycle. I’m also thrilled to announce funding will be awarded to OPEN (a new collaboration on Outcomes of Patients’ Evidence, with Novel, DIY-AP tech), a 36-month international collaboration assessing outcomes, QOL, further development, access of real-world AP tech, etc. (More to come on this soon!)

I’m also thrilled to announce funding will be awarded to OPEN (a new collaboration on Outcomes of Patients’ Evidence, with Novel, DIY-AP tech), a 36-month international collaboration assessing outcomes, QOL, further development, access of real-world AP tech, etc. (More to come on this soon!)

In summary: we don’t have a choice in living with diabetes. We *do* have a choice to DIY, and also to research to learn more and improve knowledge and availability of tools for us PWDs, more quickly. We would love to partner and collaborate with anyone interested in working with the DIY community, whether that is utilizing the #OpenAPS Data Commons for retrospective studies or designing prospective studies. If you take away one thing today: let it be the request for us to all openly share our tools, data, and insights so we can all make life with type 1 diabetes better, faster.

A huge thank you as always to the community: those who have donated and shared data; those who have helped develop, test, troubleshoot, and otherwise help power the #OpenAPS and other DIY diabetes communities.

Presentation:

Improvements in A1c and Time-in-Range in DIY Closed-Loop (OpenAPS) Users

(full tweet thread available here; or a description of this presentation below)

—

#OpenAPS is an open and transparent effort to make safe and effective Artificial Pancreas System (APS) technology widely available to reduce the burden of Type 1 diabetes. #OpenAPS evolved from my first DIY closed loop system and our desire to openly share what we’ve learned living with DIY closed loops. It takes a small, off-the-shelf computer; a radio; and a battery to communicate with existing insulin pumps and CGMs. As a PWD, I care a lot about safety: the safety reference design is the first thing in #OpenAPS that was shared, in order to help set expectations around what a DIY closed loop can (and cannot) do.

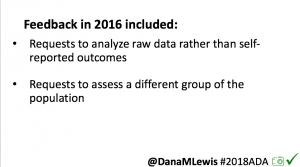

As I shared about my own DIY experience, people questioned whether it would work for others, or just me. At #2016ADA, we presented an outcomes study with data from 18 of the first 40 DIY closed loop users. Feedback on that study included requests to evaluate CGM data, given concerns around accuracy of self-reported outcomes.

As I shared about my own DIY experience, people questioned whether it would work for others, or just me. At #2016ADA, we presented an outcomes study with data from 18 of the first 40 DIY closed loop users. Feedback on that study included requests to evaluate CGM data, given concerns around accuracy of self-reported outcomes.

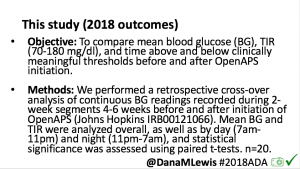

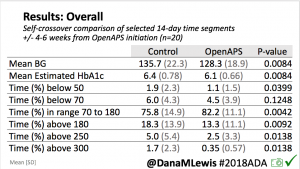

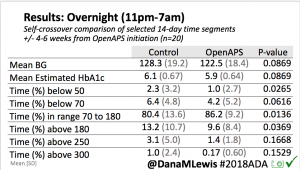

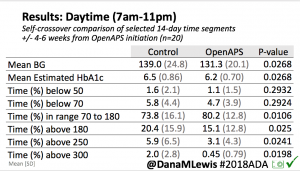

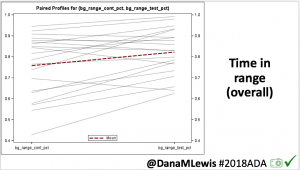

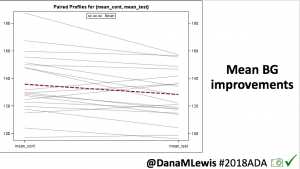

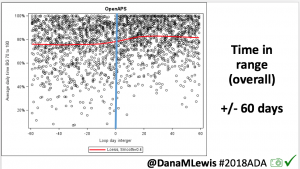

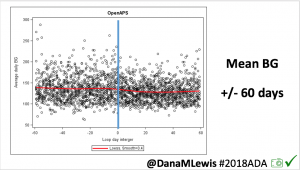

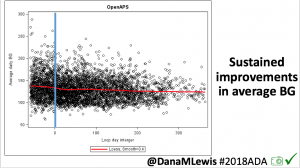

This 2018 #OpenAPS outcomes study was the result. We performed a retrospective cross-over analysis of continuous BG readings recorded during 2-week segments 4-6 weeks before and after initiation of OpenAPS.

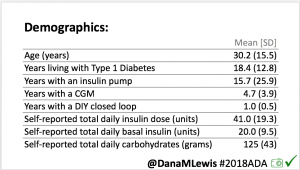

For this study, n=20 based on the availability of data that met the stringent protocol requirements (and the limited number of people who had both recorded that data and donated it to the #OpenAPS Data Commons in early 2017). Demographics show that, like the 2016 study, the people choosing to #OpenAPS typically have lower A1C than the average T1D population; have had diabetes for over a decade; and are long-time pump and CGM users. Like the 2016 study, this 2018 study found mean BG and TIR improved across all time categories (overall, day, and nighttime).

For this study, n=20 based on the availability of data that met the stringent protocol requirements (and the limited number of people who had both recorded that data and donated it to the #OpenAPS Data Commons in early 2017). Demographics show that, like the 2016 study, the people choosing to #OpenAPS typically have lower A1C than the average T1D population; have had diabetes for over a decade; and are long-time pump and CGM users. Like the 2016 study, this 2018 study found mean BG and TIR improved across all time categories (overall, day, and nighttime).

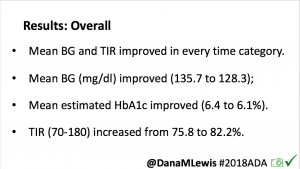

Overall, mean BG (mg/dl) improved (135.7 to 128.3); mean estimated HbA1c improved (6.4 to 6.1%). TIR (70-180) increased from 75.8 to 82.2%. Overall, time spent high and low were all reduced, in addition to eAG and A1c reduction. Overnight (11pm-7am) had smaller improvement in all categories compared to daytime improvements in these categories.

Notably: although this study primarily focused on a 4-6 week time frame pre-looping vs. 4-6 weeks post-looping, the improvements in all categories are sustained over time by #OpenAPS users.

Conclusion: Even with tight initial control, persons with T1D saw meaningful improvements in estimated A1c, TIR, and a reduction in time spent high and low, during the day and at night, after initiating #OpenAPS. Although this study focused on BG data from CGM, do not overlook additional QOL benefits when analyzing benefits of hybrid closed loop therapy or designing future studies! See these examples shared from Sulka Haro and Jason Wittmer as example of quality of life impacts of #OpenAPS.

Conclusion: Even with tight initial control, persons with T1D saw meaningful improvements in estimated A1c, TIR, and a reduction in time spent high and low, during the day and at night, after initiating #OpenAPS. Although this study focused on BG data from CGM, do not overlook additional QOL benefits when analyzing benefits of hybrid closed loop therapy or designing future studies! See these examples shared from Sulka Haro and Jason Wittmer as example of quality of life impacts of #OpenAPS.

A huge thank you to the community: those who have donated and shared data; those who have helped develop, test, troubleshoot, and otherwise help power the #OpenAPS and other DIY diabetes communities.

And, special thank you to my co-authors, Scott Swain & Tom Donner, for the collaboration on this study.

Recent Comments