I have previously written about the cost of patient participation, reflecting on some of the asks I get to be involved in various projects, conferences, etc. Since that post, I’ve been pleased with some of the asks I’ve gotten. The good ones are good: they recognize that patient time is valuable, and proactively offer to cover not only costs of travel expenses but also a reasonable honorarium or payment for my time and expertise.

The bad ones are bad, though. In some cases, really bad. Most recently, I’ve encountered asks where it feels like they are shaming me for daring to ask if participants’ expertise is being valued by providing an honorarium for their time.

There’s a lot of social nuances around ‘asking for money’ and how we value people for their time (or not). As a PI of a grant-funded project myself, I get the tradeoffs in terms of paying people for their time to contribute vs. having that money to do other project work (speaking specifically of grant-funded projects, although the same logic applies to conference & other budgets). Personally, though, I believe the right thing to do, if you’re asking for expertise that’s not already on your team (and already being paid for), is to pay for it. You’d pay a legal expert to consult on your project if there wasn’t one on your team and you needed legal expertise. If you are having others consult or provide expertise to meet one of the goals of your project, you should pay for that, too. Otherwise, you’re asking people to do things and will be spending social cash in order to get people to do things for you. If you have a bank of relationship cash, great. But, that actually limits your ability to bring in the right (or best) experts, because it assumes you already have those relationships and they’re the best people. But thinking about filter bubbles in today’s world – chances are you do not have those relationships (yet). And if these people are experts, they should be paid for their contributions toward your project.

When some of your experts are patients and others are not, it gets even tricker. You may be able to use traditional quid pro quo relationship stuff to get someone whose “day job” it is to lend their expertise to projects like yours. But for many patients, their work isn’t their “day jobs” and they’re not getting paid. As I mentioned, they’re likely having to take vacation time or unpaid leave in order to do extracurricular things. But there are other costs, too, even in the relatively simple interaction of a patient being “asked” to do things. If you’re not a patient with a chronic condition, you may not be aware of this.

—

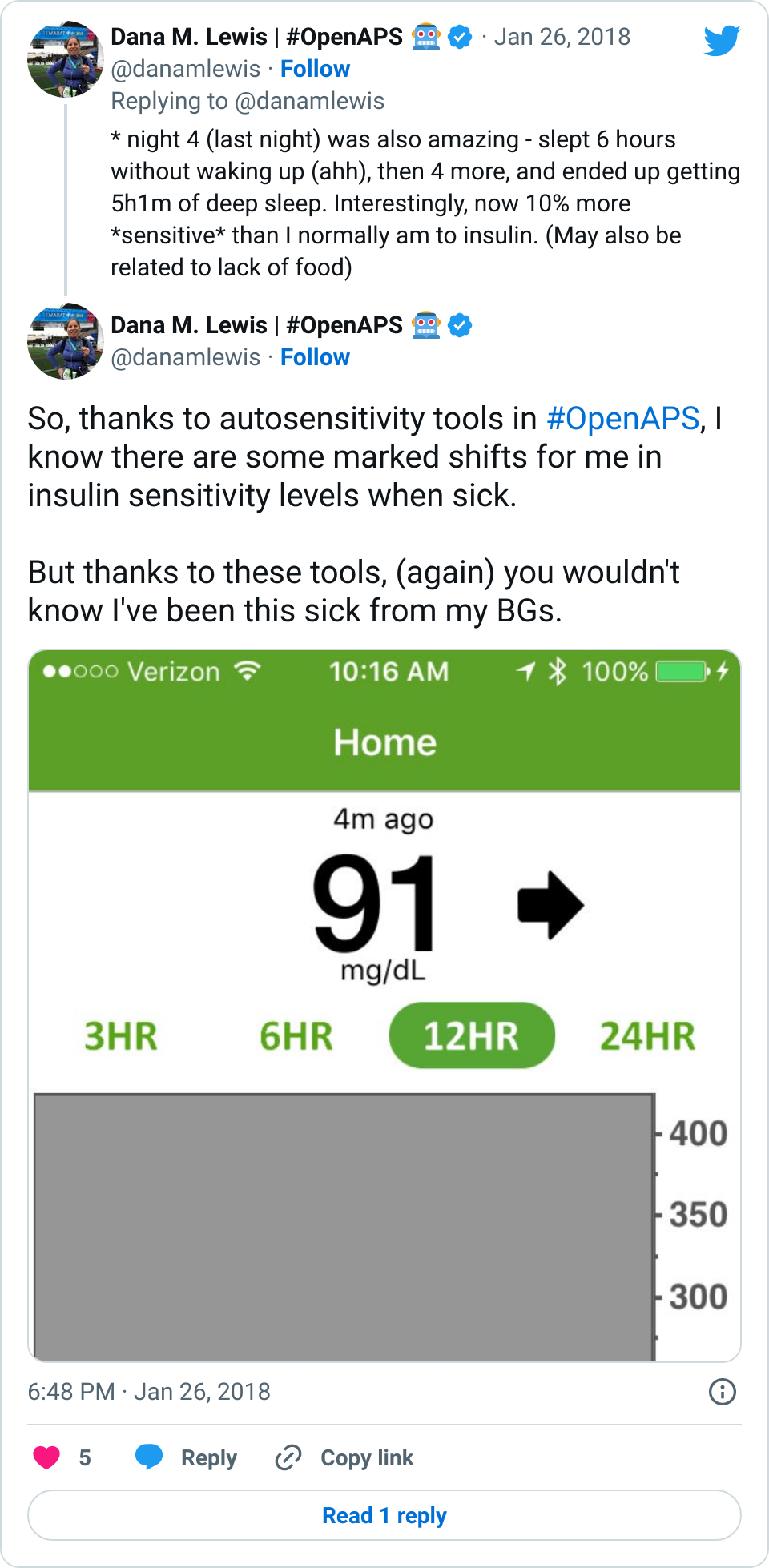

One of the ongoing struggles in being a patient with a chronic condition is not just the physical elements of the condition, and dealing with the condition itself, but also the psychosocial elements, including interacting with the world about it. Many patients are self-sufficient in managing their disease, but what about when it comes to dealing with other people who they must interface with about their needs? It’s hard. I speak from personal experience, from dealing with both type 1 diabetes and celiac. Even trying to pre-organize gluten free food at conferences, and then having to hunt down 15 humans at the conference when they “forget” and have to go see what’s gluten free…it’s a lot of work, and it’s stressful.

A friend recently shared her daughter’s experience with advocating for herself at school, based on her 504 plan. (A 504 plan is where the school and family agree up front on accommodations that the student may need, related to the medical condition. For Type 1 diabetes, that can include things like the ability to reschedule a test if the night before (or the day of), the student has exceptionally high blood sugar, because this can influence concentration and cognition, as well as making a person feel really sick.) In this instance, the daughter asked to reschedule a test and communicated her needs, but felt pressured by the teacher to take the test that day. The friend ended up having to communicate with the teacher, pointing out how her daughter did the right things, but that it’s hard for a child or teen to “stand up for themselves” to an adult – especially when meeting with resistance. This is especially true when they’re advocating for their needs based on a chronic condition.

And you know what? That’s still true even as an adult. It’s hard to always have to be different. It’s hard to have to fight 24/7/365 for your needs. Dealing with the resistance you encounter daily is *hard*. (This for me is where celiac is the more frequent pain and source of frustration. I am *so* tired of doing everything “right” in pre-requesting gluten free food due to a medical condition, and there being no gluten free food, or sub-optimal options that are not nutritious (lettuce is not a meal!). The time and energy it takes from me to deal with this takes away from my ability to participate in an event. See this thread for an example. And it happens all the time. RAR.) Sometimes it feels easier to just come up with a workaround on your own rather than rely on other people. Or to just go with the flow, and deal with the (potentially negative) outcomes of the situation. But that’s not always possible. Either way, the drain and strain of this self-advocacy adds up, and becomes exhausting.

—

So, back to asking for patient participation in projects/conferences/things. Asking a patient to participate requires them to respond to you. And in many cases, it involves them having to ask for money or asking clarifying questions. Patients often meet resistance to such requests, which is itself exhausting, especially if they get lots of asks. Based on some recent experiences, I wanted to suggest some do’s/don’ts to consider if you’re looking to ask a patient to help with something. This is by no means a comprehensive list or a “do exactly this and it’s good enough, you don’t have to think about doing the right thing anymore”. But to me, it’s a bare minimum for being able to start a conversation and to be taken seriously by patients:

DO:

- Be specific about your ask and the time commitment involved.

- Bonus: If you don’t have an existing relationship, be specific about why you think this person is a good fit and how you found them.

- (Ideally this means they’re not just filling a check box for “any patient will do, we just need a patient involved.”)

- Be upfront about what benefits and payment a patient will get.

- See my previous post about how a patient might evaluate your ask, and if you can’t pay them, be clear about it and what other value you’re offering to them.

- But really…do pay patients for their time.

DO NOT:

- Shame or guilt-trip patients.

- Yes, your project/conference/etc. is a worthwhile endeavor, and patient participation would add value. But patients help other patients all the time. For free. And there’s a limit of how much people can do, especially when it involves taking time away from where they’ve already decided to spend their time helping people. Not to mention family time, work, etc.

- Make a vague ask.

- If you ask for time/expertise and do not offer payment to the person for their time or articulate any other benefits to them, you’re putting them into an awkward position: they either have to accept the ask without a clear idea of the benefit of doing so, respond back with a difficult and awkward ask for money, or say no / ignore a reasonable-seeming request.

- Try to solely tug on the heart strings of “helping”.

- This is shaming or guilt-tripping.

- Confuse an honorarium with covering travel expenses to physically arrive at your event.

- Honorarium is something that should cover time. If you offer “an honorarium to cover the flight”, that’s a travel expense reimbursement or per diem, not payment for the value of their time.

- Ask for a coffee meeting or an introductory call based on social credibility referral from a friend/colleague, and then jump straight into “picking their expertise for free”.

- An introductory encounter should be about getting to know each other and presenting an ask to a person. (Which hey, would save time if you did it by email and were clear per the above.) Don’t mask or skip over the ask.

—

Again, this is by no means of an exhaustive list (and I’d love for other patients to add their take to it). It’s not meant to blame or shame anyone, but to open what I think is a much-needed conversation about legitimizing and sustaining patient participant and engagement, because it IS valuable. I’d love fellow researchers who work with patients to share their ideas and best practices for outreaching and inviting patients to collaborate with them. We all need to talk about this to change some of the widespread behaviors that make it hard for patients to be able to participate on projects, even when we *do* want to help.

—

meta note: Hard conversations are hard. This blog post was hard to write and publish. It makes me feel uncomfortable in the same way I do pushing back on individual asks that don’t value my contributions. As a patient, it’s hard to push back on “the way things are” – but I know it still needs to be done, even when it’s uncomfortable.

But if you’ve read all this way,

But if you’ve read all this way,

Recent Comments