“May I ask what your A1c is?”

This is a polite, and seemingly innocuous question. However, it’s one of my least favorite questions taken at face value. Why?

Well, this question is often a proxy for some of the following questions:

- How well are *you* doing with DIY closed loop technology?

- How well could *I* possibly do with DIY closed loop technology?

- What’s possible to achieve in real-world life with type 1 diabetes?

But if I answered this question directly with “X.x%”, it leaves out so much crucial information. Such as:

- What my BG targets are

- Because with DIY closed loop tech like OpenAPS, you can choose and set your own target.

- (That’s also one of the reasons why the 2018 OpenAPS Outcomes Study is fascinating to me, because people usually set high, conservative targets to start and then gradually lower them as they get comfortable. However, we didn’t have a way to retrospectively sleuth out targets, so those are results are even with the amalgamation of people’s targets being at any point they wanted at any time.)

- What type of lifestyle I live

- I don’t consider myself to eat particularly “high” or “low” carb. (And don’t start at me about why you choose to eat X amount of carbs – you do you! and YDMV) Someone who *is* eating a lot higher or lower carb diet compared to mine, though, may have a different experience than me.

- Someone who is not doing exercise or activity may also have a different experience then me with variability in BGs. Sometimes I’m super active, climbing mountains (and falling off of them..more detail about that here) and running marathons and swimming or scuba diving, and sometimes I’m not. That activity is not so much about “being healthy”, but a point about how exercise and activity can actually make it a lot harder to manage BGs, both due to the volatility of the activity on insulin sensitivity etc.; but also because of the factor of going on/off of insulin for a period of time (because my pump is not waterproof).

- What settings I have enabled in OpenAPS

- I use most of the advanced settings, such as “superMicroBoluses” (aka SMB – read more about how it works here); with a higher than default “maxSMBBasalMinutes”; and I also use all of the advanced exercise settings so that targets also nudge sensitivity in addition to autosensitivity picking up any changes after exercise and other sensitivity-change-inducing activities or events. I also get Pushover alerts to tell me if I need any carbs (and how many), if I’m dropping faster and expected to go below my target, even with zero temping all the way down.

- What my behavioral choices are

- Timing of insulin matters. As I learned almost 5 years ago (wow), the impact of insulin timing compared to food *really* matters. Some people still are able to do and manage well with “pre-bolusing”. I don’t (as explained there in the previous link). But “eating soon” mode does help a lot for managing post-meal spikes (see here a quick and easy visual for how to do “eating soon”). However, I don’t do “eating soon” regularly like I used to. In part, because I’m now on a slightly-faster insulin that peaks in 45 minutes. I still get better outcomes when I do an eating-soon, sure, but behaviorally it’s less necessary.

- The other reason is because I’ve also switched to not bolusing for meals.

- (The exceptions being if I’m not looping for some reason, such as I’m in the middle of switching CGM sensors and don’t have CGM data to loop off of.)

These settings and choices are all crucial information to understanding the X.x% of A1c.

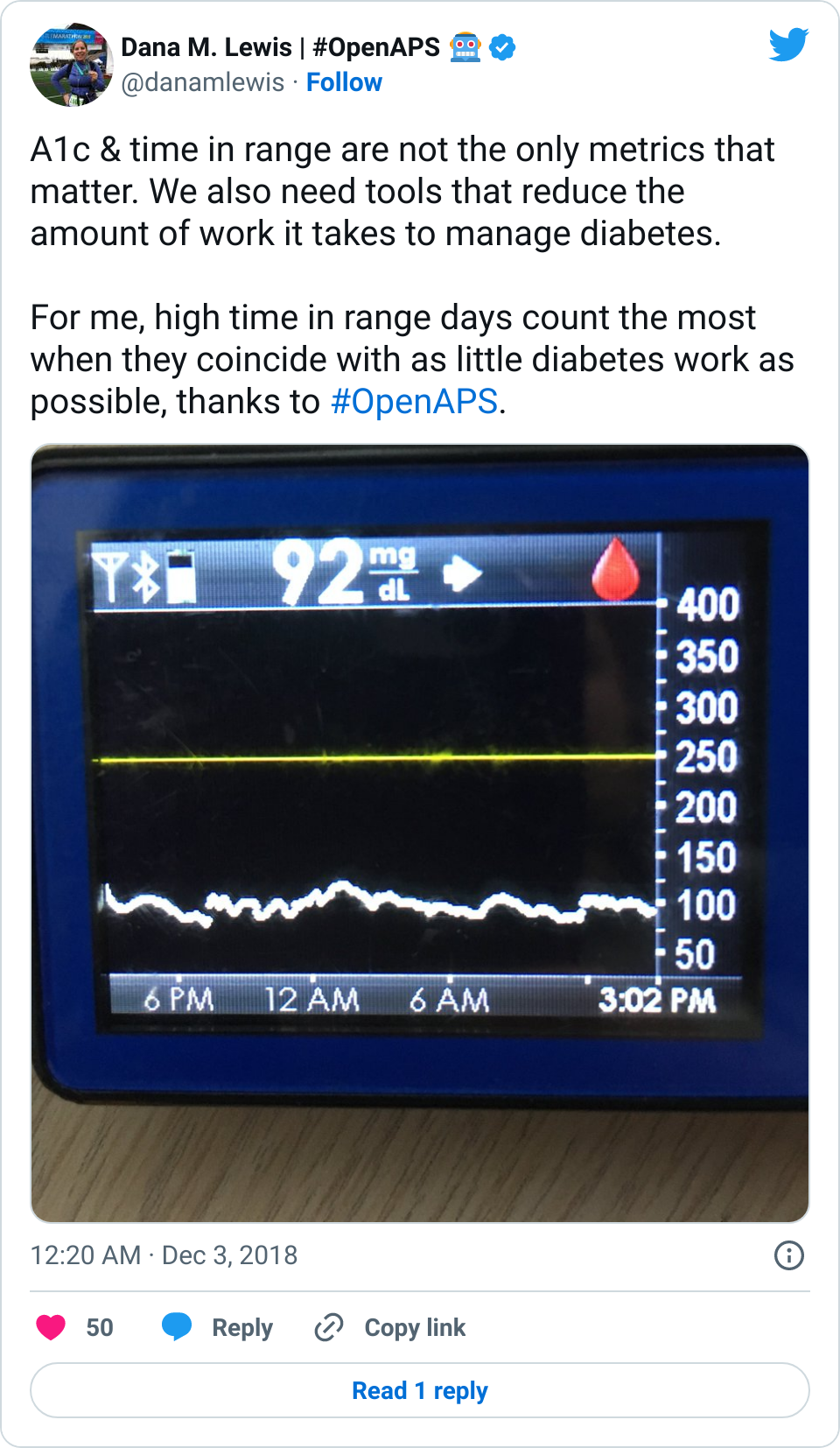

Diabetes isn’t just the average blood glucose value. It’s not just the standard deviation or coefficient of variation or % time in range or how much BG fluctuates.

Diabetes impacts so much of our daily life and requires so much cognitive burden for us, and our loved ones. That’s part of the reasons I appreciate so much Sulka & his family being candid about how their A1C didn’t change, but the amount of work required to achieve it did (way fewer manual corrections). And ditto for Jason & the Wittmer family for sharing about the change in the number of school nurse visits before/after using OpenAPS. (See both of their stories in this post)

For me, my quality of life metric has always been first about sleep: can I sleep safely and with peace of mind at night? Yes. Then – how long can I safely sleep? (The answer: a lot. Yay!) But over time, my metrics have also evolved to consider how I can cut down (like Sulka) on the amount of work it takes to achieve my ideal outcomes, and find a happy balance there.

As I mentioned in this podcast recently, other than changing my pump site (here’s how I change mine) and soaking and swapping my CGM sensors (psst – soak your sensor!), I usually only take a few diabetes-related actions a day. They’re usually on my watch, pressing a button to either enable a temp target or entering carbs when I sit down to eat.

That’s a huge reduction in physical work, as well as amount of time spent thinking/planning/doing diabetes-related things. And when life happens – because I get the flu or the norovirus or I fall off a mountain and break my ankle – I don’t worry about diabetes any more.

So when I’m asked about A1c, my answer is not a simple “X.x%”. (And not just for the reason I’m annoyed by how much judging and shaming goes on around A1c, although that influences it, too.) I usually remind people that I first started with an “open loop” for a year, and that dropped my A1c by X%. And then I closed the loop, which reduced my A1c further. And we made OpenAPS even better over the last four years, which reduced it further. And then I completely stopped bolusing! And got less lows…and kept the same A1c.

And then I ask them what they’d really like to know.  If it’s a fellow person with diabetes or a loved one, we talk about what problems they might be having or what areas they’d like to improve or what behaviors they’d like to change, if any. That’s usually way more effective than hearing “X.x%” of an A1c, and them wondering silently how to get there or what to do differently if someone wants to change things. (Or for clinicians who ask me, it turns into a discussion about choices and behaviors and tradeoffs that patients may choose to make.)

If it’s a fellow person with diabetes or a loved one, we talk about what problems they might be having or what areas they’d like to improve or what behaviors they’d like to change, if any. That’s usually way more effective than hearing “X.x%” of an A1c, and them wondering silently how to get there or what to do differently if someone wants to change things. (Or for clinicians who ask me, it turns into a discussion about choices and behaviors and tradeoffs that patients may choose to make.)

Remember, your diabetes may (and will) vary (aka, YDMV). Your lifestyle, the phase of life you’re in, your priorities, your body and health, and your choices will ALL be different than mine. That’s not bad in any way: that’s just the way it is. The behaviors I choose and the work I’m willing to do (or not do) to achieve *my* goals (and what my goals are), will be different than what you choose for yours.

And that’s therefore why A1c is not “enough” to me as a metric and something that we should compare people on, even though A1c is the “same” for everyone: because the work, time spent, behavioral tradeoffs, and goals related to it will all vary.

Recent Comments