I thought I would share some of how I am using AI. Previously I’ve talked a lot about broad concepts of prompting LLMs and the types of projects that can be done. I’ve provided particular examples that I’ve found useful for n=1 custom software (to address software-shaped feelings, often) or for improving n=1*many software like my apps PERT Pilot (iOS | Android), Carb Pilot, etc. But I haven’t talked a ton about which LLMs I use and why.

There’s a reason for that.

I noticed back in the day (of artisanal hand coding, going uphill in the snow both ways to build things) that a lot of programmers would be super dismissive and bullying about which language/program you talked about using. Let’s say you picked up a project and built it in C++: someone might come in and declare that it is the stupidest thing ever, and you should’ve used Python. But if it works in C++…who cares? The same thing about whether you use a visual “IDE” or code from the terminal, and whether you use tabs or spaces, or prefer vi or vim or nano…who cares? Use what works for you. I always noticed and hated and tried to ignore the “you should do it this way!” unless there was a “hey, heads up, doing it this way is better because very concrete reason X,Y,Z”.

So when you read my blog posts about LLMs, you might pick up on my generic use of talking about AI/LLMs without calling out a specific one (for example, see my last post where I talked about using LLMs to build solutions for software-shaped feelings). That’s because if the first one you picked up was Claude, and you liked it – great. Use that. All of my advice regarding prompting and other stuff applied. But if you used and liked ChatGPT? Also great, advice also applies. It’s easy to read (as a non-technical person) advice that’s for ChatGPT and be confused about whether you can extrapolate it to another tool and environment. That’s now exacerbated by the fact that we went from web-based AI (think ChatGPT and Claude websites) to desktop and phone-based apps to now also agentic “CLI” (command line interface) options. There’s oodles of ways to use an LLM of choice depending on where you are, what you like, and what you are trying to do. Try one and if it works for you, great. Be willing to try other things, too, but it’s fine if it doesn’t work as well for you and you keep using what does work. (If it doesn’t work, that is a good reason to try something else, as different models are better at different things and the different tools may have different capabilities).

Here’s what I have used over time, what I’ve tried and why I’ve switched over – or not switched at all.

First, I mainly used ChatGPT (web) because that’s what was available in the early days. I found it useful especially as the models progressed. I also had tried Claude when it became available (web), but didn’t find it as useful. I tried a few times with different types of projects and prompts. It was ok-ish, but I preferred ChatGPT especially for technical projects. I also tried Gemini (web) and had a similar lackluster response. I was thrilled when there became a (Mac) app for ChatGPT, and when there became more functionality like tool integration. Before, I was having to copy in code and get it to re-write or advise, then I would copy/paste code back over. (Hey, still easier than noodling over stack overflow entries and trying to figure out how it applied to my project). But, it was burdensome. Then it got to where it could see the context of my file, but only one file. That was better but still lacked the context of everything else. However, for one-off questions about random topics and other types of non-coding work, I still preferred ChatGPT’s models overall, especially increasingly the models with thinking. I now use 5.2-thinking as the default for all my work (this was written in early February 2026; assume that in future when you read this, I will probably be on the latest thinking/reasoning models).

Note: if someone says “I used GPT 5.2” when describing what they did, you have to ask what level of thinking they had it set to. Was it auto mode? Or thinking mode? Yes, sometimes auto mode will eventually trigger thinking mode but it drastically differs based on the prompt, and I find most users on free accounts using auto don’t see it go into full thinking the way my prompts get 5.2-thinking from the start, and that influences how useful the answer is. And again, it likely doesn’t have context for the project or if it does only one file’s worth.

Meanwhile, Scott has been a big fan of Claude Code, the agentic CLI for Claude’s models. He’s very, very productive with it for work on his laptop using the CLI tools. I had on my list to try CLI tools, but I put it off for a long while in part because I had finally experimented with Cursor.

I started using Cursor to test if it was better (for me) for coding-related projects. It’s basically a desktop app that I can open a project folder in and see all the files – whether they’re XCode (iOS app) files or Android Studio kotlin or javascript or python or markdown or whatever. I don’t have to open all the different ‘run’ apps to work on the code (although I still need to use XCode or Android Studio to ‘build’ and run the simulator or deploy to my physical phones for testing, these are no longer my primary interfaces for the coding work). And, this means all the files in the project are *in context* (or, able to be searched within a prompt to give it context), without me having to go tell it to look at file A for context – it can look itself and figure out which file is relevant or has the relevant code. (This is also because of the increasing capabilities of ‘agents’ which can do more sophisticated multi-step things in response to your prompts.) Cursor allows you to pick which models you want to use, so you could limit it to just Claude or ChatGPT-related models, but I don’t – I use all the latest models. I can’t really tell a difference with this setup what model is being used (!) which honestly shocked me because from the web version I *can* tell such a difference between the two, but the Cursor-style setup that has context for the full project takes away that difference. And Cursor has been very fast to iterate and instead of having it be slow to go prompt by prompt, they now have planning mode and agents where you can start by having it plan a set of work and build a checklist (even a big one with lots of tasks) and then it’ll go do some, most, or occasionally all of it. It’s also gotten better about running things in a sandbox to test its work, so I spend a lot less time on iOS projects: for example, going into XCode and having to come back to Cursor and complain about a build error that is preventing me from testing. Instead of that happening 3 of every 4 times, it now seems like it happens only 1 of 4 times and often this is a very minor issue that it fixes with a single follow up action and I can build. So that prompt>build>test timeline loop has gotten WAY faster, even just comparing the last 3 months or so. Because I have found such success with my iOS projects, Cursor has become my go-to interface of choice harness/setup for most projects, including Android apps, iOS apps, new data science projects, and anything else that involves code and/or data analysis.

However, Cursor is a desktop app. One of the benefits of ChatGPT is that I could do something on the desktop app and walk away and go for a walk and if I thought of something, pull out my phone and add another prompt to it via the phone app in the same thread that had the same context window. (Mostly – it can’t access a code file from my phone, but whatever else was loaded in the chat history it has). This means that ChatGPT was still my mobile/phone LLM of choice. I often found myself with my phone dreaming up a new project and essentially doing “planning” mode with ChatGPT (5.2-thinking, as of Feb 2026) for scoping out a project and thinking through constraints. When I was back at my laptop, I would have ChatGPT write a summary and/or prompt to give to another LLM, then go give it to Cursor. I’d have Cursor riff on that plan and add to it, then go implement it. This has worked wildly well, but I do wish I had a way to do at least planning mode with Cursor from my phone.

But, aside from that, I have felt as productive with Cursor (for laptop usage) and ChatGPT (for phone based and non-coding usage) as Scott does with Claude Code (on his laptop; he also uses ChatGPT as his phone LLM of choice).

Lately, you might have heard about “OpenClaw” (aka “MoltBot” aka “ClawdBot” – it had a few name changes). It’s a security nightmare, so don’t just use it if you’re not thinking it through, but the TL;DR is that it’s a way to set up a way to send prompts to an LLM and have it run them on your computer, with full access to all the different tools and accounts you’ve set up. However, it’s a security nightmare and very risky, so most people shouldn’t be using it (including you, probably). The only reason I’m bringing it up is because I *wish* I had a way for mobile commands to a coding LLM that had access to my code, so I could basically instruct Cursor to work on something while I’m away from my laptop. But, I am not willing to set something up with permissions to remote control my laptop fully (which is basically what OpenClaw does), so I haven’t been able to do so.

Until this weekend.

I kept thinking that what I wanted was the ability to remotely prompt Cursor, because it has access to the full project. There are a few ways to do this, either via something like OpenClaw (nope, see above) or if you host your code on Github and run ‘cloud’ based LLMs on it. I didn’t want to do that, the projects I have are local on my computer, and I want the LLM to have context and ability to write code and edit code on that project. (Otherwise, I’ll just use ChatGPT which is sufficient on my phone for other things). This could be because I’m away from my laptop – cross country skiing in the mountains and thinking through projects and wanting to start a prompt on the drive home so it can have something for me to review and test when I’m back, or just in the other room and don’t want to go get my laptop out. If only there was a way to have Cursor check a Google Sheet, for example, for a new prompt and then go run it.

Light bulb.

Cursor (desktop) can’t, but a scheduled job on my computer could be set up to check a Google Sheet every so often and find the prompt and send it to an LLM agent that can be run on my laptop. I could have the LLM log the prompt and what it did and the output, so even though I wouldn’t see it in the ‘chat history’ of the desktop app the way I do with ChatGPT or Cursor (desktop), I could still review a summary of what it thought/did and review the code when I was back on my laptop. (Bonus: because this project folder is synced to a backup cloud that I have access to on my phone, I can review this from my phone, too!).

How did I figure this out and make it work? I used ChatGPT (as my phone-based brainstorm LLM app of choice) to talk through the idea and talk through technical options, including my ‘requirements’/preferences of not using Github/cloud based actions for this. This discussion laid out a plan and I was surprised that the Cursor CLI (as opposed to desktop) would work for this, which means I could download Cursor CLI and log in/set that up (under the same account I used Cursor Desktop with), and with a simple script I added to my Mac via Terminal, have it check the Google Sheet at the designated interval, find the prompt, run it, record the status in the sheet plus record a status in the log of the project.

So after all, I am finally using a CLI for an LLM! (Although, I will say after I downloaded it and installed and logged in just to set it up for this project, I actually hate the UI, go figure, so my resistance to CLI-based LLMs was probably an intuitive strong preference for GUI-based LLMs.) But I’m not using it directly as a CLI, my script on my Mac is calling it to do the work based on the prompt I put into a Google Sheet. Google Sheets, which I’m very comfortable with, becomes the place I prompt my code-based LLM to do remote work from. (FYI, for setup, I’m also using a free Google Cloud Console Project which you give permissions to which is part of the way it can read/write from the Google Sheet remotely.)

End to end, this setup involved 1) terminal (on my Mac); 2) Cursor CLI; 3) Google Cloud Console; 4) Google Sheets.

I will have to continue to set this up for other projects that I want to do, but the bulk of the hard work is done – the additional projects will be a few minutes of configuration and testing each time, so I’ll do that every time I touch those projects and find myself wanting to do remote work.

But this is exactly what I love about AI-driven development. You can build amazing things that would not have been in your wheelhouse to even attempt before. You can troubleshoot and fix all kinds of issues along the way on the big ambitious project that becomes a realistic option to build and implement, whether it’s just for you or it’s something that a lot of other people would use. And, you can use it to customize your environment and tools and make up completely new tools (again, which you never would’ve thought was possible to do before!) that enable you to do work in ways that weren’t possible before. I keep saying this, but it’s worth keeping a log somewhere of projects that are still “too hard” and coming back to them every few months and trying them again with newer models or setups. (If you haven’t used anything with ‘agents’, you REALLY should try this on a project.)

It’s exciting to keep adding to existing projects, building new projects you didn’t have time to do before, and building the projects that you only figured out how to dream up with the help of new technology.

It’s exciting to keep adding to existing projects, building new projects you didn’t have time to do before, and building the projects that you only figured out how to dream up with the help of new technology.

The point isn’t convincing you to want to use my app. Most people don’t have a use case for this. But I want more people to build the patterns of recognizing when their feelings are trying to tell them something (e.g. this is a problem we could work on improving, even if it is not solvable) and build the skills of identifying when this is a software-shaped feeling. Especially when we are dealing with health-related situations and especially chronic non-curable diseases, and especially ones with treatments or medications that are not fun, it is so important to solve friction and frustration whenever and wherever we can. Not everything is a software-shaped feeling, but the more we recognize and address, the better off we are. Or at least I am, and I hope to help others do the same.

The point isn’t convincing you to want to use my app. Most people don’t have a use case for this. But I want more people to build the patterns of recognizing when their feelings are trying to tell them something (e.g. this is a problem we could work on improving, even if it is not solvable) and build the skills of identifying when this is a software-shaped feeling. Especially when we are dealing with health-related situations and especially chronic non-curable diseases, and especially ones with treatments or medications that are not fun, it is so important to solve friction and frustration whenever and wherever we can. Not everything is a software-shaped feeling, but the more we recognize and address, the better off we are. Or at least I am, and I hope to help others do the same.

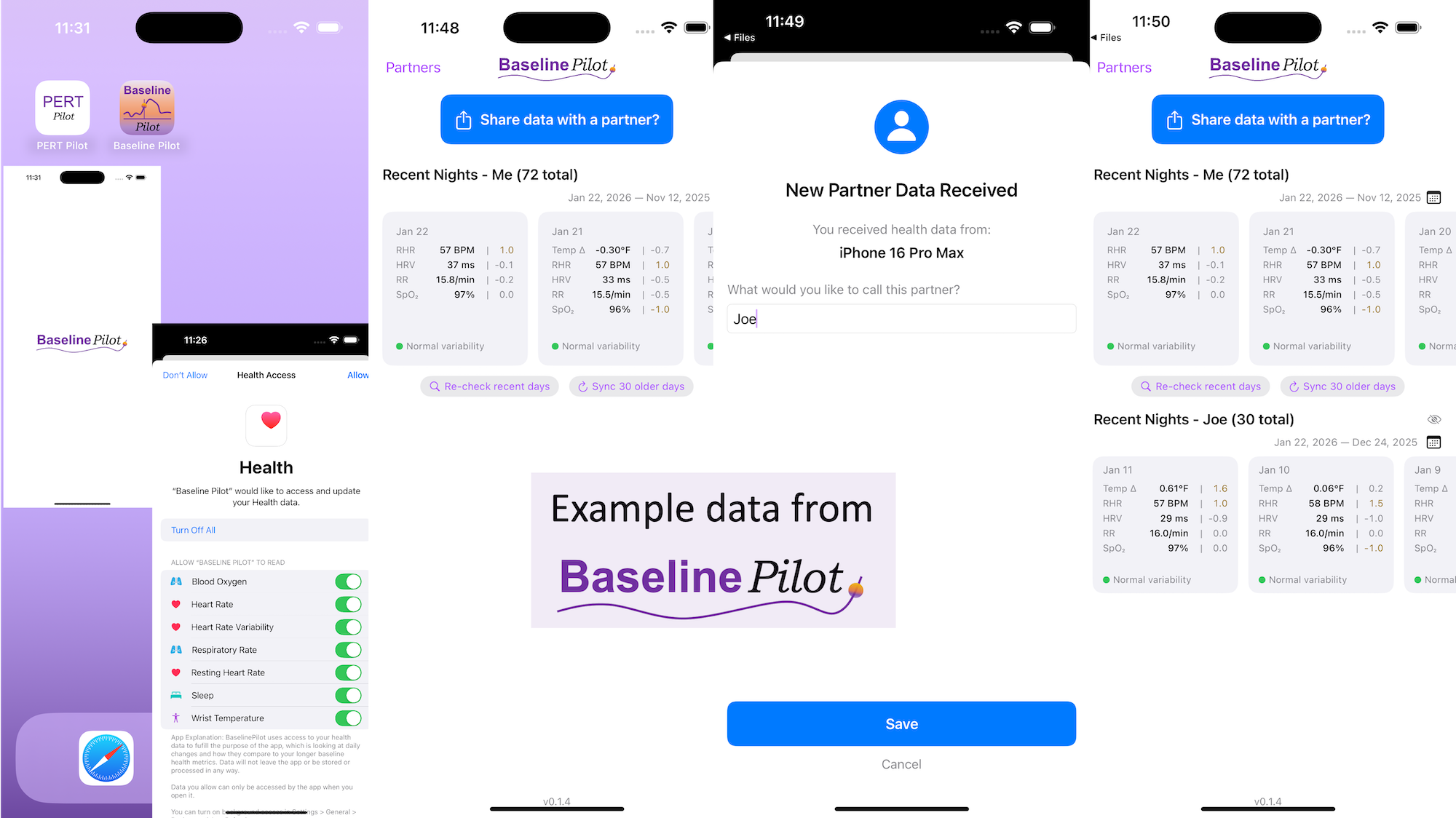

All of this data is local to the app and not being shared via a server or anywhere else. It makes it quick and easy to see this data and easier to spot changes from your normal, for whatever normal is for you. It makes it easy to share with a designated person who you might be interacting with regularly in person or living with, to make it easier to facilitate interventions as needed with major deviations. In general, I am a big fan of being able to see my data and the deviations from baseline for all kinds of reasons. It helps me understand my recovery status from big endurance activities and see when I’ve returned to baseline from that, too. Plus the spotting of infections earlier and preventing spread, so fewer people get sick during infection season. There’s all kinds of reasons someone might use this, either to quickly see their own data (the Vitals access problem) or being able to share it with someone else, and I love how it’s becoming easier and easier to whip up custom software to solve these data access or display ‘problems’ rather than just stewing about how the standard design is blocking us from solving these issues!

All of this data is local to the app and not being shared via a server or anywhere else. It makes it quick and easy to see this data and easier to spot changes from your normal, for whatever normal is for you. It makes it easy to share with a designated person who you might be interacting with regularly in person or living with, to make it easier to facilitate interventions as needed with major deviations. In general, I am a big fan of being able to see my data and the deviations from baseline for all kinds of reasons. It helps me understand my recovery status from big endurance activities and see when I’ve returned to baseline from that, too. Plus the spotting of infections earlier and preventing spread, so fewer people get sick during infection season. There’s all kinds of reasons someone might use this, either to quickly see their own data (the Vitals access problem) or being able to share it with someone else, and I love how it’s becoming easier and easier to whip up custom software to solve these data access or display ‘problems’ rather than just stewing about how the standard design is blocking us from solving these issues!

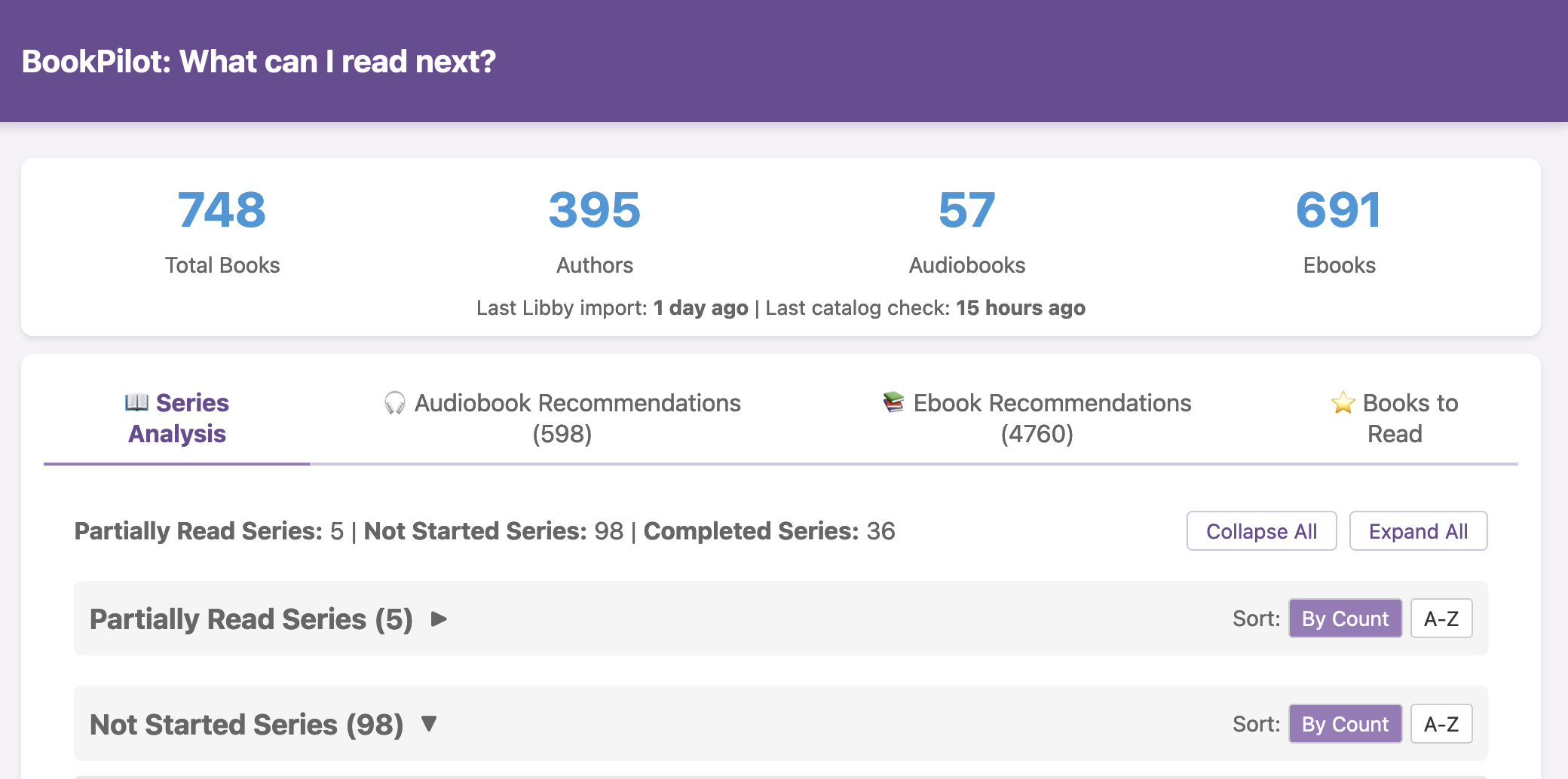

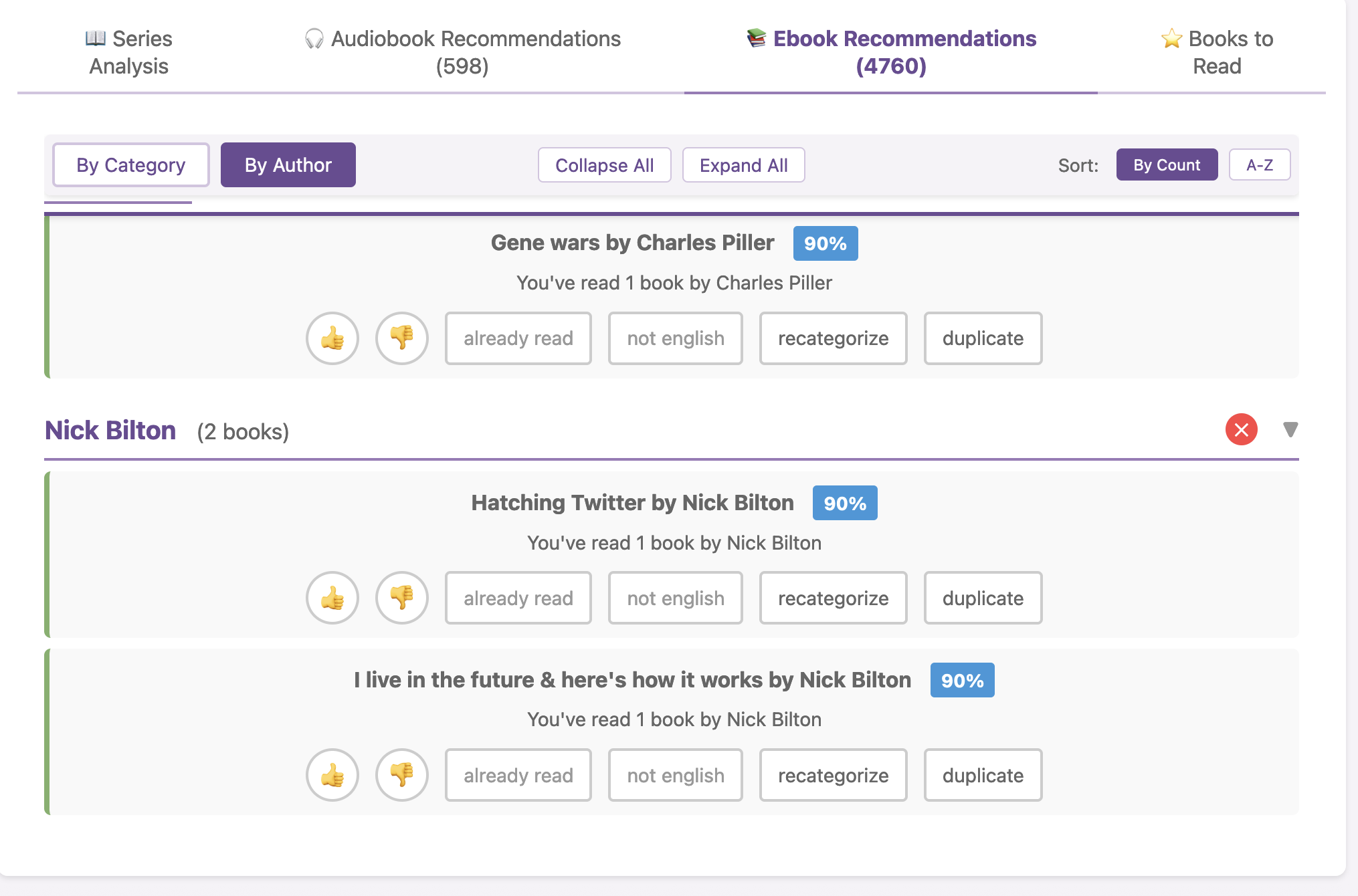

I haven’t open-sourced BookPilot yet, but I can (

I haven’t open-sourced BookPilot yet, but I can ( I know some of the answers to the question of why clinicians aren’t doing this. But, the question I asked the Stanford AI+Health audience was to consider why we focus so much on informed consent for taking action, but we ignore the risks and negative outcomes that occur when not taking action.

I know some of the answers to the question of why clinicians aren’t doing this. But, the question I asked the Stanford AI+Health audience was to consider why we focus so much on informed consent for taking action, but we ignore the risks and negative outcomes that occur when not taking action. AI often gives us new capabilities to do these things, even if it’s different from the way someone might do it manually or without the disability. And for us, it’s often not a choice of “do it manually or do it differently” but a choice of “do, with AI, or don’t do at all because it’s not possible”. Accessibility can be about creating equitable opportunities, and it can also be about preserving energy, reducing pain, enhancing dignity, and improving quality of life in the face of living with a disability (or multiple disabilities). AI can amplify our existing capabilities and super powers, but it can also level the playing field and allow us to do more than we could before, more easily, with fewer barriers.

AI often gives us new capabilities to do these things, even if it’s different from the way someone might do it manually or without the disability. And for us, it’s often not a choice of “do it manually or do it differently” but a choice of “do, with AI, or don’t do at all because it’s not possible”. Accessibility can be about creating equitable opportunities, and it can also be about preserving energy, reducing pain, enhancing dignity, and improving quality of life in the face of living with a disability (or multiple disabilities). AI can amplify our existing capabilities and super powers, but it can also level the playing field and allow us to do more than we could before, more easily, with fewer barriers. These are actionable, doable, practical things we can all be doing, today, and not just gnashing our teeth. The sooner we course correct with improved data availability, the better off we’ll all be in the future, whether that’s tomorrow with better clinical care or in years with AI-facilitated diagnoses, treatments, and cures.

These are actionable, doable, practical things we can all be doing, today, and not just gnashing our teeth. The sooner we course correct with improved data availability, the better off we’ll all be in the future, whether that’s tomorrow with better clinical care or in years with AI-facilitated diagnoses, treatments, and cures.

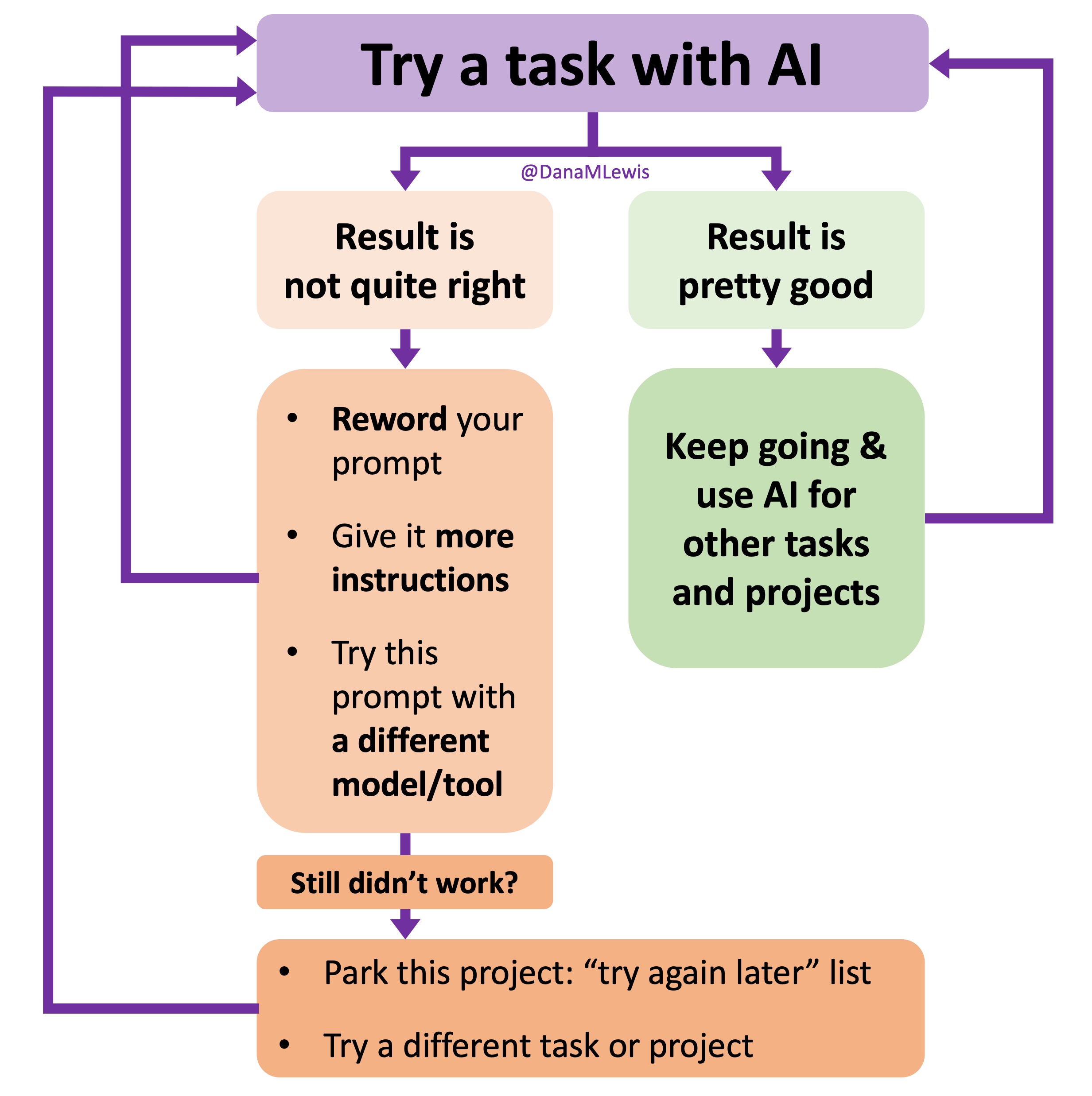

I’ve started making a list of projects or tasks I want to work on where the AI isn’t quite there yet and/or I haven’t figured out a good setup, the right tool, etc. A good example of this was

I’ve started making a list of projects or tasks I want to work on where the AI isn’t quite there yet and/or I haven’t figured out a good setup, the right tool, etc. A good example of this was  TL;DR: as more and more people are going to vibe code their way to having Android and/or iOS apps, it’s very feasible for people with less experience to do both and to distribute apps on both platforms (iOS App Store and Google Play Store for Android). However, there’s an up front higher cost to iOS ($99/year) but a slightly easier, more intuitive experience for deploying your apps and getting them reviewed and approved. Conversely, Android development, despite its lower entry cost ($25 once), involves navigating a more complicated development environment, less intuitive deployment processes, and opaque requirements for app approval. You pay with your time, but if you plan to eventually build multiple apps, once you figure it out you can repeat the process more easily. Both are viable paths for app distribution if you’re building iOS and Android apps in the LLM-era of assisted coding, but don’t be surprised if you hit bumps in the road for deploying for testing or production.

TL;DR: as more and more people are going to vibe code their way to having Android and/or iOS apps, it’s very feasible for people with less experience to do both and to distribute apps on both platforms (iOS App Store and Google Play Store for Android). However, there’s an up front higher cost to iOS ($99/year) but a slightly easier, more intuitive experience for deploying your apps and getting them reviewed and approved. Conversely, Android development, despite its lower entry cost ($25 once), involves navigating a more complicated development environment, less intuitive deployment processes, and opaque requirements for app approval. You pay with your time, but if you plan to eventually build multiple apps, once you figure it out you can repeat the process more easily. Both are viable paths for app distribution if you’re building iOS and Android apps in the LLM-era of assisted coding, but don’t be surprised if you hit bumps in the road for deploying for testing or production.

Recent Comments