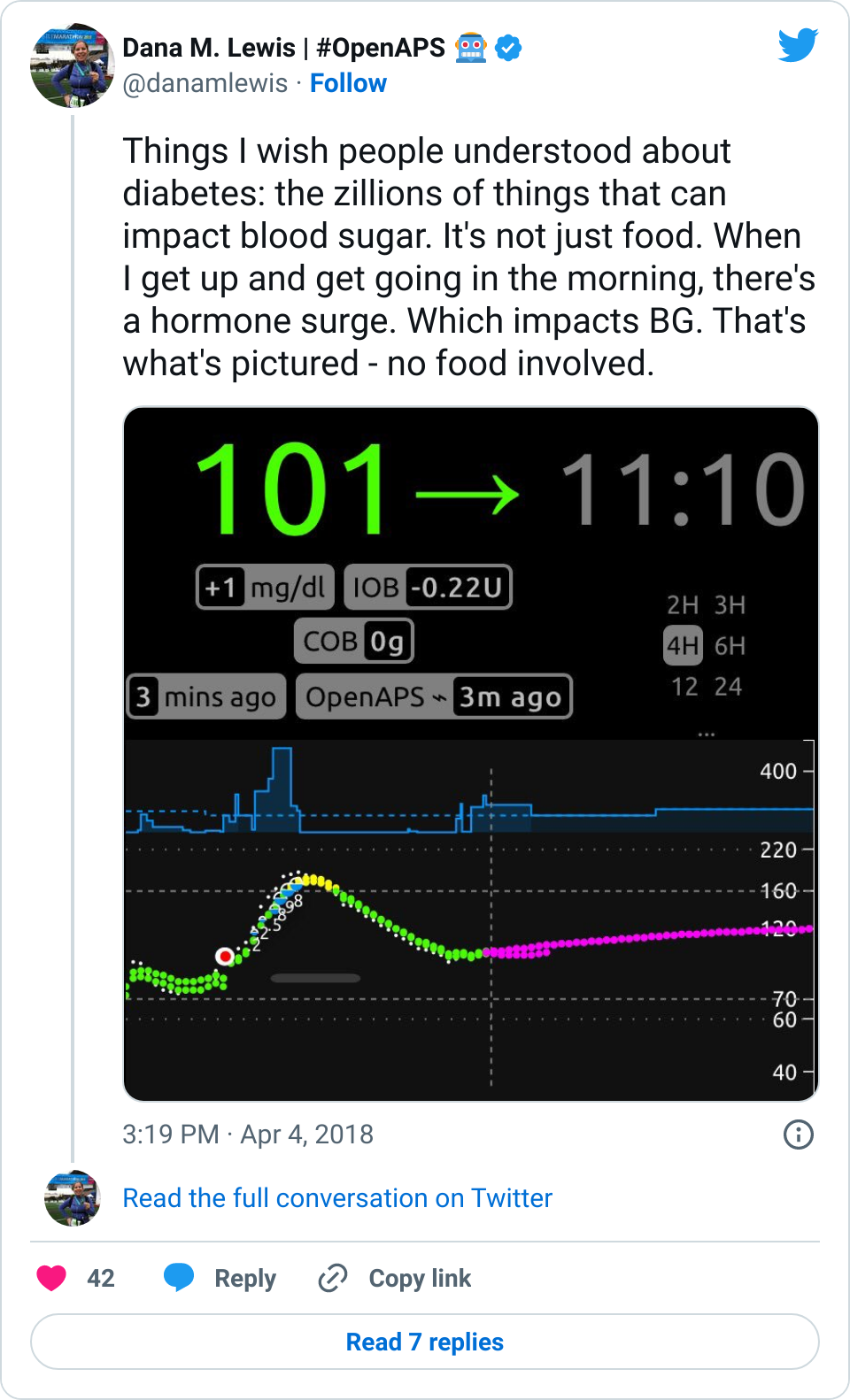

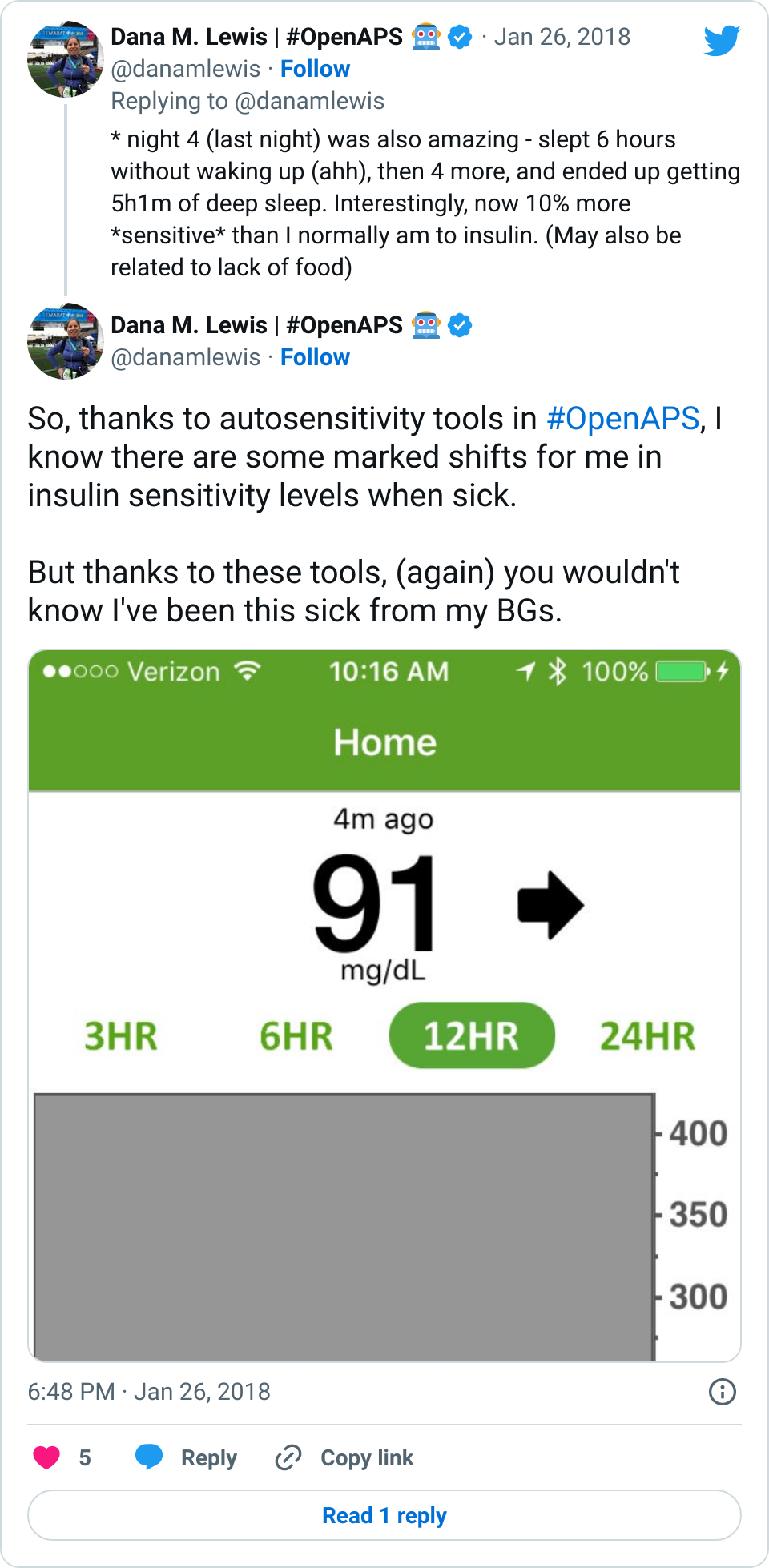

I posted one of my Nightscout graphs yesterday, showing a snapshot of my morning:

I hadn’t eaten, and my blood sugar still spiked up. I’ve noticed this happens in the mornings sometimes. When I have mentioned it over the years, people are quick to tell me my basal rates are wrong, and I should adjust them because dawn phenomenon. But actually, this isn’t dawn phenomenon. This happens after I physically get up and start moving for the day, whether that happens at 4am, or 6am, or 10am, or even waking up after noon. So, it’s not a basal thing, and modifying my basal rates doesn’t fix it. (And this is why I wanted to add wake-up mode to my suite of tools, to help address this.)

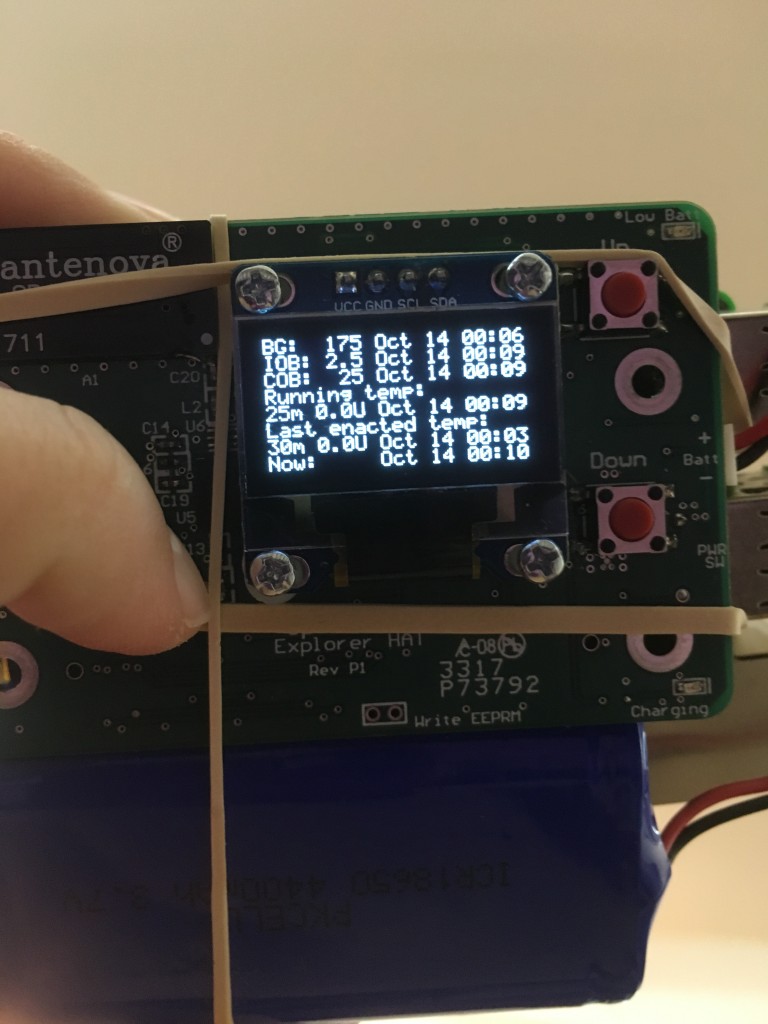

To me, this is a great example, (as I mentioned in my Twitter thread), of why diabetes is so hard: sooooo many things impact BG levels, and in many cases, we PWDs just have to roll with it and respond the best we can. In my case, #OpenAPS did a great job responding to the spike and bringing me back down within an hour or so.

One of the questions that popped up yesterday in response to that graph, though, was about the BG line: how did I have two BG lines?

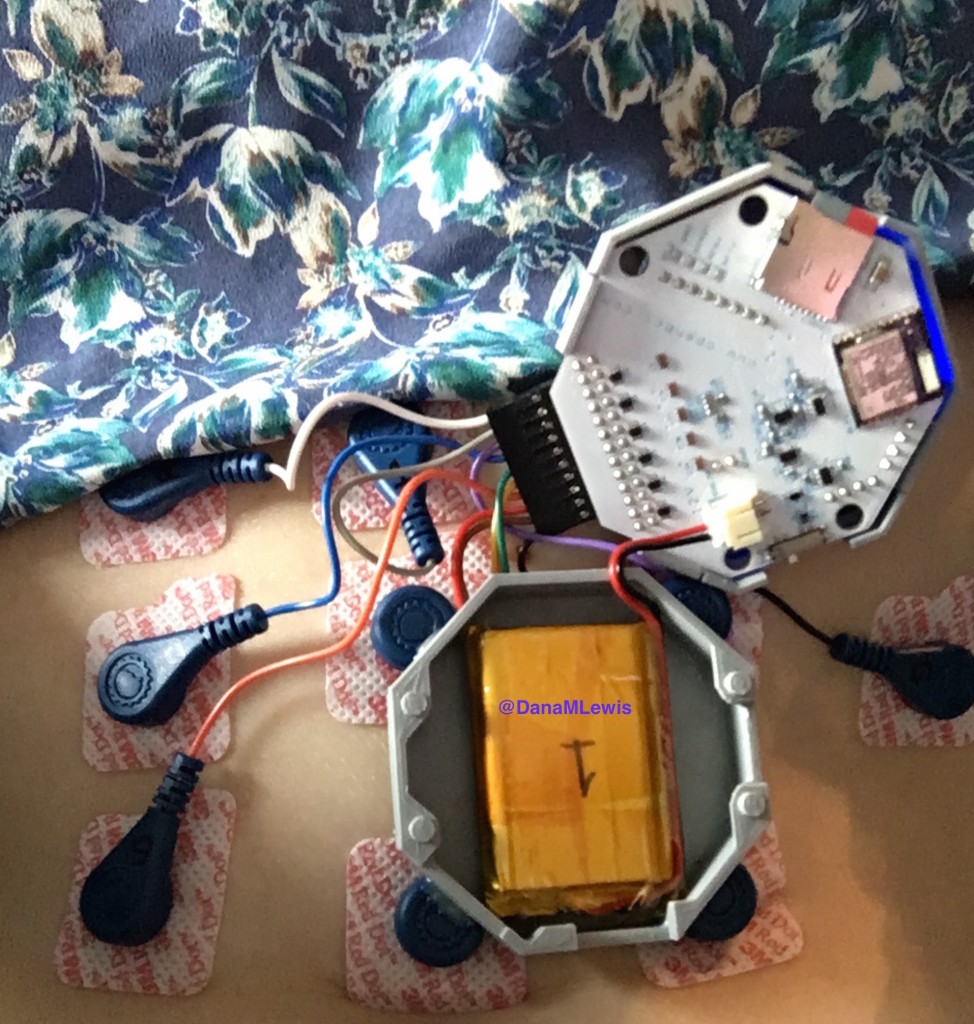

The answer: I wear a G4 sensor, and usually have 2 receivers running off the same transmitter and sensor. One receiver is Share-d to my phone, and uploads to NS via the interwebz. The other receiver, although Share-capable, doesn’t (because the company only allows you to pair one receiver and upload via Share). I leave that CGM plugged into a rig to enable it to be a backup for offline looping. When online, this rig with the plugged in CGM uploads BGs from that receiver to NS.

Sometimes, because of different start/stop times and therefore differing calibration records, the receivers “drift” from each other, making it obvious on the graph when that happens.

Because if you give a mouse a cookie, other questions come up, someone had also asked me why I’m using G4, and why not G5. Someone else asked me in a different channel why I’m not using G5 and xDrip+ (a DIY option that doesn’t use Dexcom app or a Dexcom receiver for receiving the data or processing it), or another DIY tool to process my CGM data.

Now, as always, what I chose to use is my personal preference. It’s colored by my preference for what equipment I’m willing to carry; what phone I want to use; what data I want to have; my safety backup preferences; what my insurance covers and what I can afford; where I live; etc. So, just because I use this method, doesn’t mean I expect anyone else to want to do it. It’s just what I do. I don’t try to convince other people to use this method, and I also hope others can share info about what works for them without trying to hammer me over the head because what I’m doing is different. This is where YDMV (your diabetes may vary) comes in. It’s so true, and even within “people who DIY”, there’s a ton of variation – and that’s a good thing! I adore having options to find what works for me, and I want to have other people have options and choices to choose what works for them.

That being said, here’s the answer to how I run my CGMs and some of the things that have factored into my choice to not DIY CGM receivers/data processing most of the time:

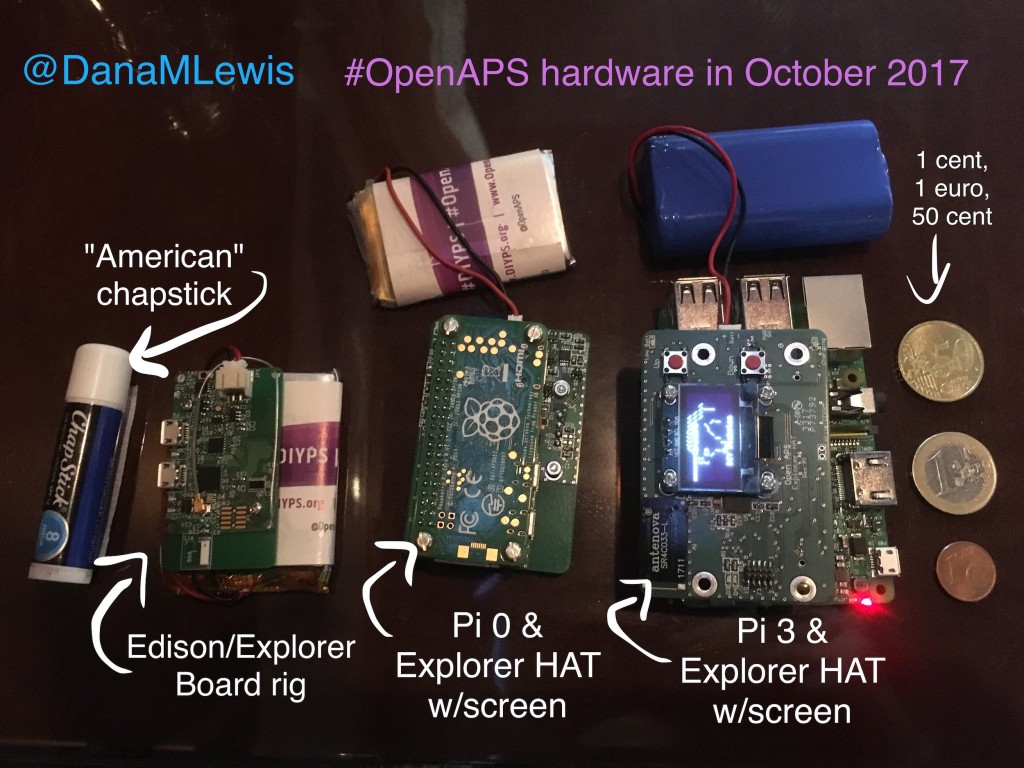

- With two G4 receivers, I can keep one in my pocket, paired to my phone and uploading via Share. When I’m out and about in the city or usually during the day, this is what I carry. When I run, I take the Share receiver.

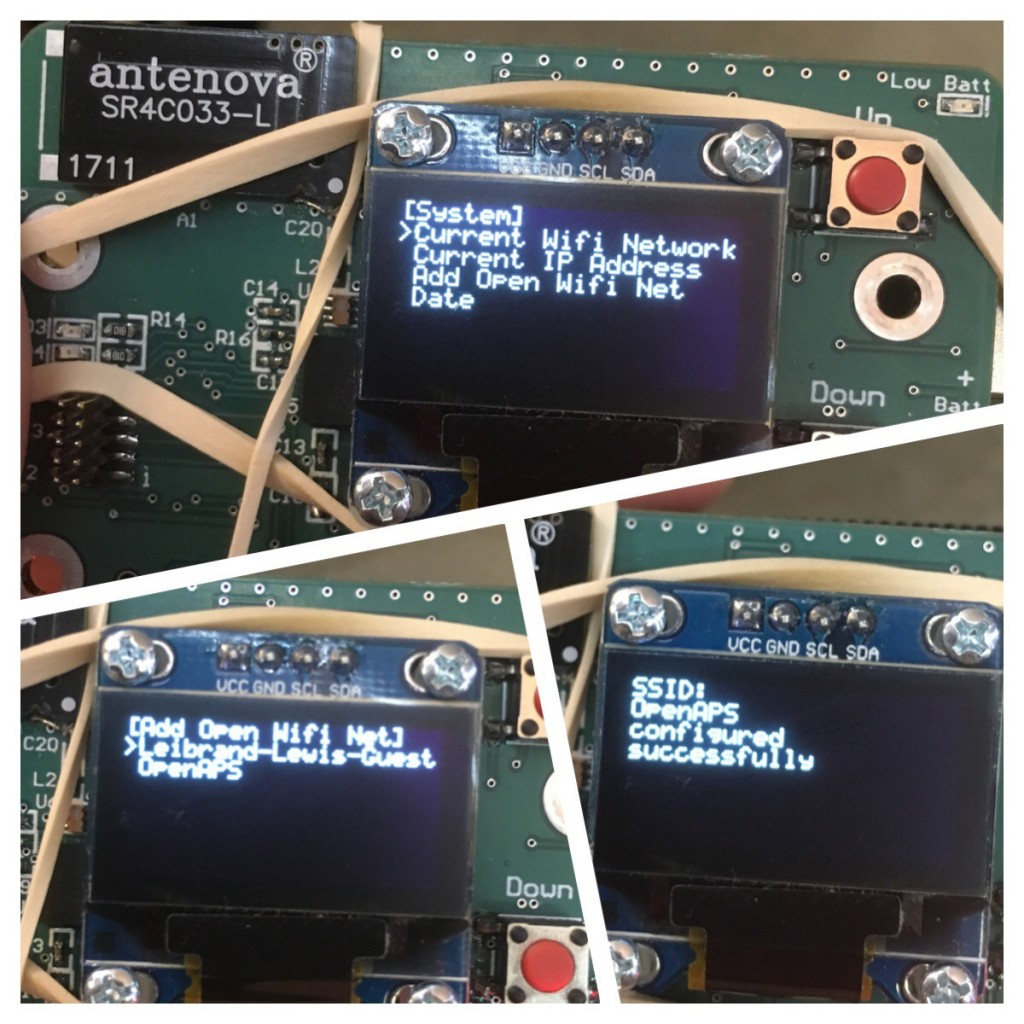

- But, I also like emergency back-ups. I like keeping a receiver plugged into an #OpenAPS rig so that if connectivity goes out/down, I can keep looping without a break in my stride. So, I could keep my Share receiver plugged into the rig, but that would involve me unplugging and replugging fairly frequently when I run errands or actually go for a short run, and meh. Hassle. So I keep “non-Share” receiver as the one that’s usually plugged into my ‘offline’ rig.

- Having the G4 receiver plugged into the rig enables me to see raw data. Raw data is nice for a couple of things: assessing the health of my sensor (if it gets jumpy compared to the filtered data, I know the quality of the sensor is decreasing, and that helps me decide when to change it); giving me a clue to what’s going on when the filtered data goes to ??? or during the start up of a new sensor; and actually being able to run my rig and loop off some* of the raw data when I need to. (*With OpenAPS, you can choose to loop off of it within a certain range, and there’s an option to only set a certain amount of correction for a proportion of what otherwise would be proposed, with a higher level of raw data.)

- With two receivers running, that also gives me more flexibility around sensor changes. Technically, the sensor is approved for 7 days. At the end of the 7 days, the receiver stops giving you data and forces you to “start” a new sensor session. That could be by inserting a new sensor; or it could be the same sensor on your body. But either way, theoretically it’s a 2 hour ‘warm up’ period from that session where you can’t see data. With 2 receivers, I can stagger the end and start of sensor sessions. I usually set a calendar alarm to restart one of the receivers on the night of the 6th day of the session, allowing me more flexibility on day 7 to choose when to restart or change my sensor.

- This also means I can choose to “hot swap” when actually changing a sensor. I may choose to not hit ‘stop’ and ‘start’ on a sensor session on one of the receivers, but rather shut it off for about 30 minutes, and just do the stop/start on the other receiver (leaving it plugged into a rig to upload raw data to NS, and be able to see where the new sensor’s readings come in compared to the old one). When I power the non-restarted receiver back on about 30m after swapping the transmitter over to the new receiver (as soon as the raw readings have flattened out), it usually either goes to “no signal” for a few minutes, and then comes back with some data, an hour or more before the restarted sensor allows me to calibrate it and get data. There are downsides to this method: the data on the receiver that didn’t get restarted can be fairly inaccurate, as it’s still using the calibrations from the old sensor. So I don’t always do that, but when it’s more important to me to be able to see relative trend of where BG is (flat, or dropping or spiking), it’s nice to have that option. And since I often soak my new CGM sensors, the data from “day 1” of the sensor after a session “start” on the receiver is often better than if it was truly day 1 of the sensor being in my body.

Phew. Maybe that sounds like a lot of work, but the above setup works well for me for a variety of reasons, and also allows me the flexibility and choice for when I change sensors, when I am forced to be without data or potentially not loop, etc. Given that my schedule varies a lot, it helps since I’m not consistently in the same time zone and what works for starting or changing sensors one week in one part of the world doesn’t always align with convenience exactly 168 hours (7 days) later in another part of the world that I’m in, doing something differently.

Some of the reasons I haven’t switched to G5 include the fact that the transmitters only last for ~3 months instead of 6+ months; I’ve observed many people being frustrated by sensor not talking to the phone even when it’s right beside them; there’s no raw data on G5; you can’t have multiple receivers paired with your transmitter; etc.

Now, you might say, but that’s using Dexcom’s app, etc. With DIY solutions, those limitations don’t apply! And that’s true, to a degree – savvy folks in the community have figured out how to make it so you don’t *have* to use Dexcom’s app to display or process the data; you can replace the batteries on the transmitter; etc. But, just like my method above of using raw data isn’t necessarily going to work for everyone or might not be something someone else choose to do, the DIY options that go with G5 (or even G4 in some cases), aren’t something I believe is the right thing to do for me.

A lot of it comes down to safety. When we first started designing my DIY closed loop, we spent eons discussing how we could do this safely for me. And that evolved into further discussions about how other people could do this safely, too. A core of the OpenAPS Reference Design is that we are using already approved and vetted devices that exist on the market (e.g. existing pumps and CGMs). Those devices include approved and vetted methods for CGM data processing, too, which is even more important when the CGM data is being used to dose insulin as in OpenAPS. Now – this is not a requirement we can enforce: people can do what they want, and some people are even using non-CGMs (such as the Libre, a “Flash Glucose Monitoring” solution, plus a DIY NFC reader) as a CGM source for looping. But, whether it’s a DIY app or algorithm on CGM data, or a different glucose measuring device that’s not a CGM, that’s choice has some safety implications that I hope people are aware of.

First, the background for those who aren’t familiar: the CGM companies display a processed (“filtered”) version of the CGM data. That’s part of their proprietary stuff, but there’s reasons behind it: the raw data can be hectic and weird, and individual readings aren’t the point, anyway. The beauty of CGM is you can see the trends in addition to the estimated BG number. In some scenarios, such as during sensor starts, during error messages that are displayed as ???, etc, the companies/FDA decided that the CGM should not show data, and instead show an error message/symbol, to help prevent anyone from making incorrect treatment decisions based off of confusing or misleading data. That’s good enough most of the time. As mentioned above, there are edge cases when seeing the raw is helpful, but most of the time, I’m happy with the filtered data.

But to me, there’s a difference between using raw or DIY-calibrated data for edge cases, vs. using them all the time. I’ve seen several cases in just the past few days with a newer “DIY CGM app”, which uses its own calibration algorithm for processing the unfiltered CGM readings. These people have reported the app displaying normal BGs (say, 90 mg/dL), while they found themselves in the 40’s (rather low). It’s not clear whether that is due to the app’s calibration algorithm, something the user did in testing and calibrating, or if it’s just a bad sensor, and since most of them are not using the official receiver/app in parallel, that’s difficult to figure out. But regardless, it’s happened enough times across numerous people for me to be concerned about a DIY CGM app being used as the primary source of CGM data. There are limitations to using company-built apps or physical devices for CGMs, but in the case where people can afford it, for safety I think it is important to at least use the approved and vetted receiver/app in parallel, to provide a backup and baseline level of alerting and alarming. The FDA & the companies have worked to create something that can be reliable for alarming when your BG is actually low (say <55 mg/dl) and alerting a human that something is going on. This is important regardless of whether people are looping or not, but it’s perhaps even more important when people are looping, since that data is driving insulin dosing decisions. Additionally, the company-created devices have been designed to deal with miscalibrations that aren’t in line with what the data from the receiver is showing, and have safety measures in place to “reject” calibrations and request new ones when necessary. Sure: there are times where that’s frustrating, but those features truly are “there for safety”, and are important for avoiding the rare but potentially serious outcomes that could be caused by incorrect CGM readings. Since safety is what we prioritize and design around in DIY closed looping, I hope people will consider that ,and prioritize safety first when choosing what to use as their primary data source.

—

Tl;dr – YDMV. I currently use G4 with two receivers, for the reasons described above. I think it’s important to prioritize safety over convenience most of the time, and understand the limitations of the solution that you choose (DIY or commercial). But everyone’s different, and their situation, preferences, etc. may drive different decision making. And did I mention YDMV?

But if you’ve read all this way,

But if you’ve read all this way,

Recent Comments