tl;dr – automate a trigger to your #OpenAPS rig to start “wake up” mode (or “eating soon”, assuming you eat breakfast) without you having to remember to do it.

Yesterday morning, I woke up and headed to my desk to start working. Because I’m getting some amazing flat line overnights now, thanks to my DIY closed loop (#OpenAPS), I’m more attuned to the fact that after I wake up and start moving around, my hormones kick in to help wake me up (I guess), and I have a small BG rise that’s not otherwise explained by anything else. (It’s not a baseline basal problem, because it happens after I wake up regardless of it being 6am or 8am or even 10:30am if I sleep in on a weekend. It’s also more pronounced when I feel sleep deprived, like my body is working even harder to wake me up.)

Later in the morning, I took a break to jot down my thoughts in response to a question about normal meal rises on #OpenAPS and strategies to optimize mealtimes. It occurred to me later, after being hyper attuned to my lunch results, that my morning wake-up rise up from 1oo perfectly flat to ~140 was higher than the 131 peak I hit after my lunchtime bowl of potato soup.

Hmm, I thought. I wish there was something I could do to help with those morning rises. I often do a temporary target down to 80 mg/dL (a la “eating soon” mode) once I spot the rise, but that’s after it’s already started and very dependent on me paying attention/noticing the rise.

I also have a widely varied schedule (and travel a lot), so I don’t like the idea of scheduling the temp target, or having recurring calendar events that is yet another thing to babysit and change constantly.

What I want is something that is automatically triggered when I wake up, so whether I pop out of the bed or read for 15 minutes first, it kicks in automatically and I (the non-morning person) don’t have to remember to do one more thing. And the best trigger that I could think of is when I end Sleep Cycle, the sleep tracking app I use.

I started looking online to see if there was an easy IFTTT integration with Sleep Cycle. (There’s not. Boo.) So I started looking to see if I could stick my Sleep Cycle data elsewhere that could be used with IFTTT. I stumbled across this blog post describing Sleep Cycle -> iOS Apple HealthKit -> UP -> Google Spreadsheet -> Zapier -> Add to Google Calendar. And then I thought I would add another IFTTT trigger for when the calendar entry was added, to then send “waking up” mode to #OpenAPS. But I don’t need all of the calendar steps. The ideal recipe for me then might be Sleep Cycle -> iOS Health Kit -> UP -> IFTTT sends “waking up mode” -> Nightscout -> my rig. However, I then learned that UP doesn’t necessarily automatically sync the data from HealthKit, unless the app is open. Hmm. More rabbit holing. Thanks to the tweet-a-friend option, I talked to Ernesto Ramirez (long time QS guru and now at Fitabase), who found the same blog post I did (above) and when I described the constraints, then pointed me to Hipbone to grab Healthkit sleep data and stuff it into Dropbox.

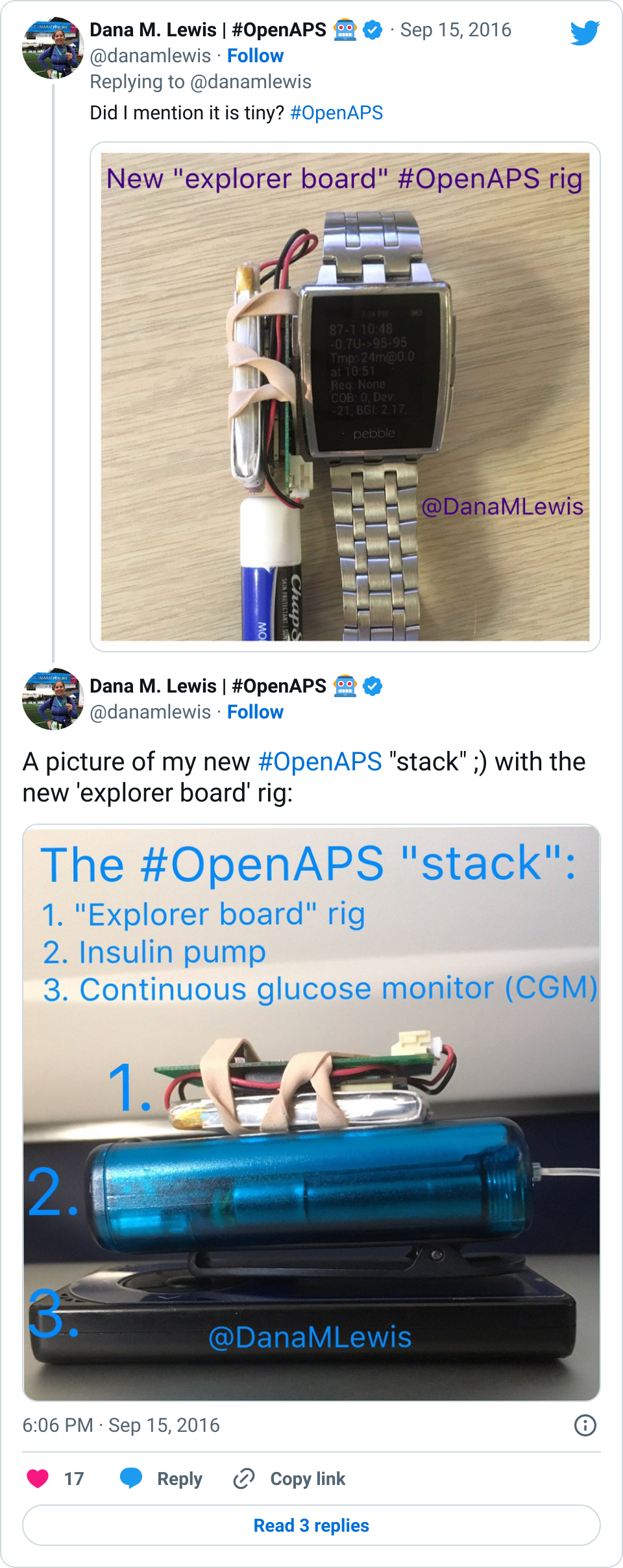

(Why Sleep Cycle? It is my main sleep tracker, but there’s IFTTT integration with Fitbit, Jawbone Up, and a bunch of other stuff, so if you’re interested in this, figure out how to plug your data into IFTTT, otherwise follow the OpenAPS docs for using IFTTT to get data into Nightscout for OpenAPS, and you’ll be all set. I’m trying to avoid having to go back to my Fitbit as the sleep tracker, since I’m wearing my Pebble and I was tired of wearing 2 things. And for some reason my Pebble is inconsistent and slow about showing the sleep data in the morning, so that’s not reliable for this purpose. )

Here’s how I have enabled this “wake up” mode trigger for now:

- If you’re using Sleep Cycle, enable it to write sleep analysis data to Apple HealthKit.

- Download the Hipbone app for iPhone, connect it with your Dropbox, and allow Hipbone to read sleep data from HealthKit.

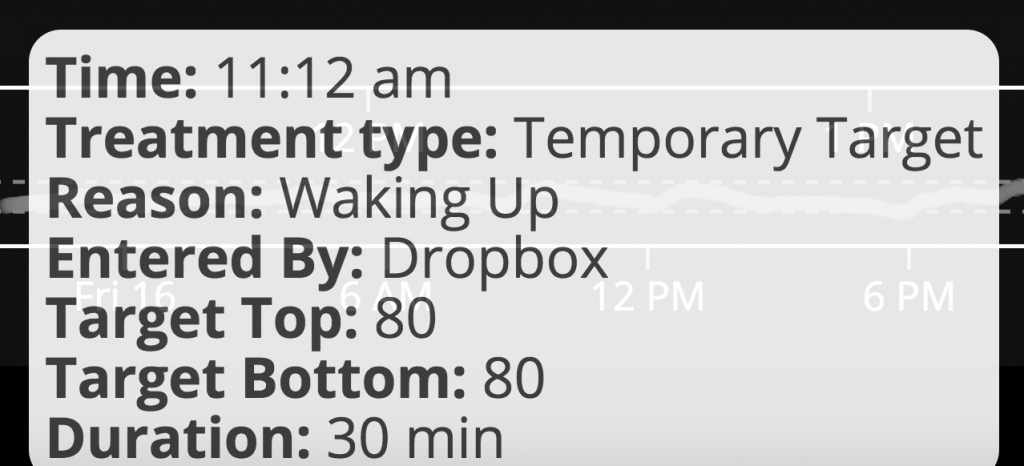

- Log in or create an account in IFTTT.com and create a recipe using Dropbox as the trigger, and Maker as the action to send a web request to Nightscout. (Again, see the OpenAPS docs for using IFTTT triggers to post to Nightscout, there’s all kinds of great things you can do with your Pebble, Alexa, etc. thanks to IFTTT.) To start, I made “waking up” soon a temporary target to 80 for 30 minutes.

Guess what? This morning, I woke up, ended sleep cycle, and ~10-11 minutes later got notifications that I had new data in Dropbox and checked and found “waking up” mode showing in Nightscout! Woohoo. And it worked well for not having a hormone-driven BG rise after I started moving around.

Ideally, this would run immediately, and not take 10-11 minutes, but it went automatically without me having to open Hipbone (or any other app), so this is a great interim solution for me until we find an app that will run more quickly to get the sleep data from HealthKit.

We keep finding great ways to use IFTTT triggers, so if you have any other cool ones you’ve added to your DIY closed loop ecosystem, please let me know!

You’re welcome as always to ping me across any channel, but often when there’s a good question, I’m going to want you to re-post in Gitter, anyway, so people can benefit from having the knowledge (including any answers from the community) archived for the next person who has the same or similar question.

You’re welcome as always to ping me across any channel, but often when there’s a good question, I’m going to want you to re-post in Gitter, anyway, so people can benefit from having the knowledge (including any answers from the community) archived for the next person who has the same or similar question.

Recent Comments