As I wrote in a previous post with much more detail (see here), I fell off a mountain and broke my ankle in three places, then managed to break a bone in my 5th toe on the other foot. This meant that my right ankle was in a hard cast for 6 weeks and I was 100% non-weight bearing…but this was challenging because the foot meant to be my stable base for crutching or knee scootering was often pretty wobbly and in a lot of pain.

This post is a follow up with more detailed tips and lessons learned of things that were helpful in living with a leg cast, as well as what the return to weight bearing was really like. I couldn’t find a lot of good information about the transition to weight bearing was really like, so this is my take on information I was looking for and would have appreciated before and during the weight bearing progression process. (And if you’re looking for diabetes-specific stuff, it’s in the last section!)

Dealing with lack of energy and fatigue

First, it’s worth noting something major about a fractured bone, and *especially* true if it’s a big bone fracture like some of mine were: it takes a lot of healing, which means a lot of energy going to the healing and not much energy left for every day living. I was constantly exhausted – and surprised by this fatigue – pretty much throughout this process. It made sense in the early days (say weeks 1-2 after fracture), but was frustrating to me how little I had energy to do even in the 4-6 weeks after my fracture.

But, then it got worse. Returning to weight bearing took *even more* energy. For example, on the first day of partial weight bearing, I was tasked with putting 25 lbs of weight on my foot in the walking boot. First by placing my foot on the scale and getting reliable with being able to put the right amount of weight on the boot; then by standing and repeating with the scale; then taking a few steps (with the crutches taking the rest of my weight) and re-calibrating with the scale until I was confident in that weight. With weight bearing progression, you’re supposed to spend up to an hour a day working on this.

I took to heart what my ortho said about not progressing fast if you only do 5-10 minute chunks, so after the first day, I tried to always do 10-15 minute chunks at a minimum, with a longer chunk wherever possible as permitted by pain and my energy levels.

But the first few days were really, really tough. It was hard to switch to a new weight every two days – because this meant readjusting how I was stepping/walking, and how much weight and where I placed my crutches. I started with a blister on my right palm, which turned into a squished nerve that made my right hand go numb, and ultimately damaged some tendons in my right wrist, too. This made it painful to use the crutches or even drive my knee scooter when I wasn’t focusing on weight bearing. So I had a lot of pain and suffering in the WB progression process that probably contributed to how fatigued I was overall.

So one of my biggest pieces of advice for anyone with broken bones is to expect your energy to take a(nother) dip for the first few weeks after you start returning to weight-bearing (or return to normal activity outside your cast). It’s a *lot* of work to regain strength in atrophied muscles while still also doing the internal healing on the broken bones!

Tips to deal with so much fatigue as you return to weight bearing:

Some of the tips and things I figured out for being non-weight bearing and sitting around with a hard cast came in handy for the weight-bearing progression fatigue, too.

- I got a shower bench (this is the one I got) so that it was easy to sit down on and swing my legs over into the shower/bathtub. Once I was out of my hard cast, I still can’t weight bear without the boot, so I still need a sitting shower/bath solution while I return to weight bearing. I also removed the back after a while, so it was easier to sit in either direction depending on preference (washing hair/not) without having to ask Scott to remove the back and re-attach it on the other side.

- Speaking of showers, I put a toothbrush and toothpaste in the shower so I can also brush my teeth there while seated.

- I still keep most of my toiletries in the bedside table (or you could have a caddy by the bedside) so I can brush my hair, take my contacts out or put them in, wipe my face (facewipes instead of having to stand at the sink to wash my face), etc. from the bed.

- I am taking ibuprofen 4x a day, and I get tired of opening the bottle. So I dumped a pile of ibuprofen on my bedside table to make it easy to reach and remember to take first thing in the morning or at night. (There are no kids or pets in my household; keep safety in mind if you have kids etc in your household – this solution may not work for you).

- The one time I tended to forget to proactively take my medication was mid-day, so I added a recurring calendar event to my calendar saying “take ibuprofen if you haven’t 2x a day” around 2pm, which would be the latest I would take my second round, even if I woke up later in the day and my first dose was later in the morning. This has helped me remember multiple times, especially on weekends or times when I’m away from my desk or bed where I would have the meds visible as a reminder.

- Pre-mix protein powder (this is what I chose) into the beverage of choice in advance, and keep it in individual containers so it’s easy to get and take (and if I’m really tired, round tupperware containers that have measurement lines make it easy to measure liquid into, put the lid on to shake it up, and drink out of without having to find another cup). I had Scott do this several days in advance when he went on a trip, and we kept doing it in advance even after he got home.

- I kept using my portable desk for working, taking video calls propped up in the bed with pillows behind me, and also laying the surface flat to eat meals from when I was too tired to get out of the bed.

Other advice for the return to weight-bearing:

If you’re like me, you’ll switch back to weight-bearing accompanied by getting out of your hard cast and getting a walking boot of some sort. If you can, ask your ortho/doc in advance what kind of boot they’ll put you in. It’s often cheaper to get the boot yourself. Perfect example: my ortho didn’t tell me what kind of boot I would need, and I looked at various boots online and saw they ranged $50-100 on Amazon. At my appointment he asked if I brought a boot and since I didn’t, they’d provide one..and the paperwork I signed stated the price would be $427 (::choking::) if the insurance didn’t cover it. Insurance negotiated down to $152 for me to pay out of pocket for since I haven’t hit my deductible…which is still 2-3x more than retail cost. UGH. So, if you can, buy your walking boot via retail. (Same goes for purchasing a knee scooter (here’s the one I got) – it may be cheaper to buy it new through Amazon/elsewhere than getting a medical purchase that goes through insurance and/or trying to do a rental.)

- You’ll also probably end up with a boot with lots of velcro straps. When you undo your boot, fold back the strap on itself so it doesn’t stick to the boot, another strap, your clothes, etc.

- Get multiple ankle braces. I had a slightly structured ankle brace with hard sides that made me feel safer the first few nights sleeping out of the cast, and it was often easier to go from the bed to the bathroom on my knee scooter or crutches with the ankle brace(s) instead of re-putting on my walking boot and taking it off again for a shower. (I transitioned to sleeping in a lighter ankle brace after a week or so, but still used the structured brace inside the waterproof cast bag for swimming laps to help protect my ankle.)

- An ice pack with a strap to put around your ankle/broken joint. I had gotten this ice pack for my knee last fall, and strap it and another ice pack to my ankle to get full joint coverage.

- Wide leg athletic pants…ideally ones that you can put on/off without having to take your boot off. (Women should note I found better athletic pants for this purpose in the men’s athletic section at Target..but be aware a lot of the modern men’s style have tapered legs so make sure to watch out for those and have enough width to get over your boot). Taking off the boot is exhausting with so many velcro straps, so any time I can get dressed or undressed without having to remove the boot if I am not otherwise removing the boot is a win.

- Look online for your state’s rules for a temporary handicap parking pass, and take the paperwork to your first ortho appointment to get filled out. Also, make sure to note where the places are that you can drop off the paperwork in person (in Seattle it was not the same as the DMV offices!), or otherwise be aware of the time frame for mailing those in and receiving the pass. The handicap parking placard has been helpful for encouraging me to get out of the house more to go to the store or go to a restaurant when otherwise I’m too exhausted to do anything.

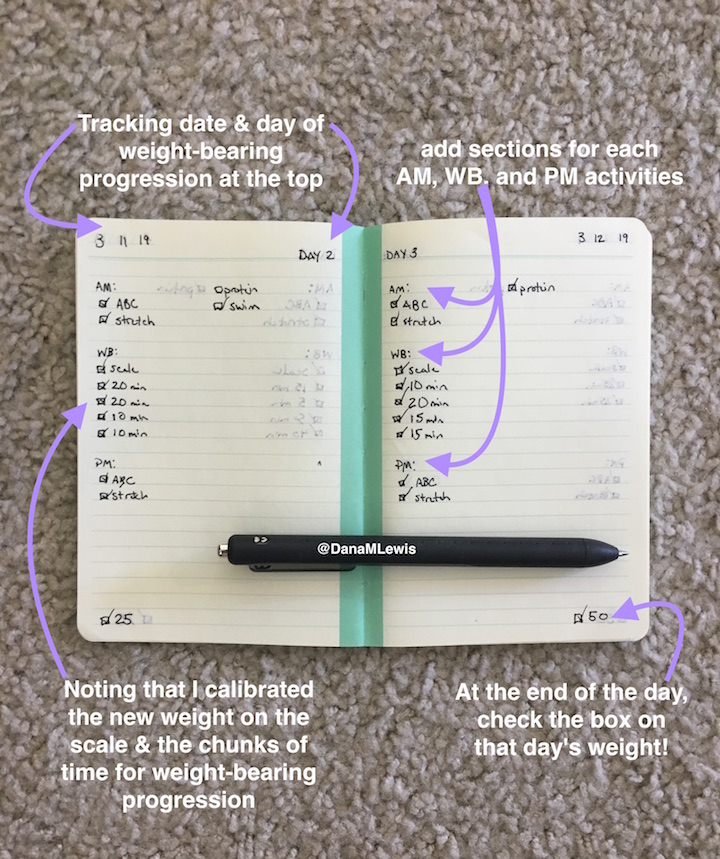

- A new shiny notebook for writing down your daily activities and what you did. If you’re not a notebook type person, use an app or note on your phone. But despite being mostly digital, I liked having a small notebook by the bed to list my daily activities and check the box on them to emphasize the activities I was doing and the progress I was making. At the beginning, it was helpful for keeping track of all the new things I needed to do; in the middle, it was useful for emphasizing the progress I was making; and at the end it felt really good to see the light of the end of the tunnel of a few pages/days left toward being fully weight bearing.

Other tips for getting used to a walking boot and transitioning to weight bearing:

- Don’t be surprised if you have pain in new areas when you move from a hard cast to a walking boot. (Remember you’ll be moving your leg or limbs in different ways than they’ve been accustomed to).

- My ortho told me the goal of weight bearing progression is to understand the difference between discomfort (lasts a few minutes) and pain (lasts a few hours). You’re likely going to be in discomfort when doing weight bearing progression – that’s normal. Pain (i.e. sharp pain) is not normal, and you should take a break or back down to a previous weight (follow your protocol) if you have it. I was lucky – the only few times I had pain was from trying to press down forcefully on the scale when seated, rather than standing on the scale and naturally letting my weight on my leg. I didn’t end up plateauing at any weight, and was able to follow my protocol of 25lb weight bearing added every 2 days and get to full weight bearing with no delays.

- If you have a watch with a stopwatch feature, use it. It’s hard to keep track of actual time spent walking (especially at first when 90 seconds feels like 6 minutes) with just a normal watch/clock. You could also use your smartphone’s timer feature. But tracking the time and pausing when you pause or take a break helps make sure you’re accurately tracking toward your hour of walking.

- The process wasn’t without discomfort – physical and emotional. Putting weight on my leg was scary, and every new weight day was hard as I dealt with the fear and processing of the discomfort, as well as learning how to step and walk and do my crutches in a new way yet again.

- But what I learned is that the first 5 minutes of every new weight day ALWAYS sucked. Once I recognized this, I set the goal to always tough out a 15 minute session after I calibrated on the scale by walking slowly around my apartment. (I put my headphones in to listen to music while I did it). As long as there was only discomfort and not pain, I didn’t stop until after 15 minutes of slow walking with that weight and also re-calibrated on the scale during and after to make sure I was in the right ballpark.

- I had to spend the first half hour or so working on my weight bearing by myself. I couldn’t talk on the phone or talk with Scott while I did it; it required a lot of concentration. (The only thing I could do is listen to music, because I’m used to running with music). So distractions did not help when I got started, but toward the end of the hour I could handle and appreciate distractions. Same for day 2 of a weight – having distractions or a task to do (e.g. walk from A to B, or walking while my nephew was on his scooter) helped pass the time and get me to complete my hour or more of weight-bearing work.

- Be careful with your hands and wrists. Blisters are common, and I managed to both squish a nerve (which caused me to have a numb side of my hand and be unable to type for several days) and also pull or damage tendons on both sides of my wrists. I was torn between choosing to delay my weight bearing progression work, but also recognizing that the sooner I got to full weight bearing the sooner I could completely ditch my crutches and be done hurting my hands. So I chose to continue, but in some cases shortened my chunks of WB walking down to 15 minutes wherever possible to reduce the pain and pressure on my hands.

Don’t you usually talk about diabetes stuff on this blog? 😉

(If anyone finds this post in the future mainly for ankle fracture and weight bearing transition/progression tips, you can ignore this part!)

Diabetes-wise, I’ve had a pretty consistent experience as to what I articulated in the last post about actually breaking bones.

- It was common for my first few days of progressive weight bearing to have a small pain/stress rise in my BGs. It wasn’t much, but 20-30 points was an obvious stress response as I did the first few 15 minutes of weight bearing practice. The following days didn’t see this, so my body was obviously getting used to the stress of weight bearing again.

- However, on the flip side, the first week of weight bearing progression also caused several lows. The hour of walking was the equivalent of any new activity where I usually have several hours later delayed sensitivity to insulin out of nowhere, and my blood sugars “go whoosh” – dropping far more than they normally would. I had two nights in a row in the first week where I woke up 2-3 hours after I went to sleep and needed to eat some carbs. This normally happens maybe once every few months (if that) now as an OpenAPS user, so it was obviously associated with this new surge of physical activity and hard work that I was doing for the weight bearing.

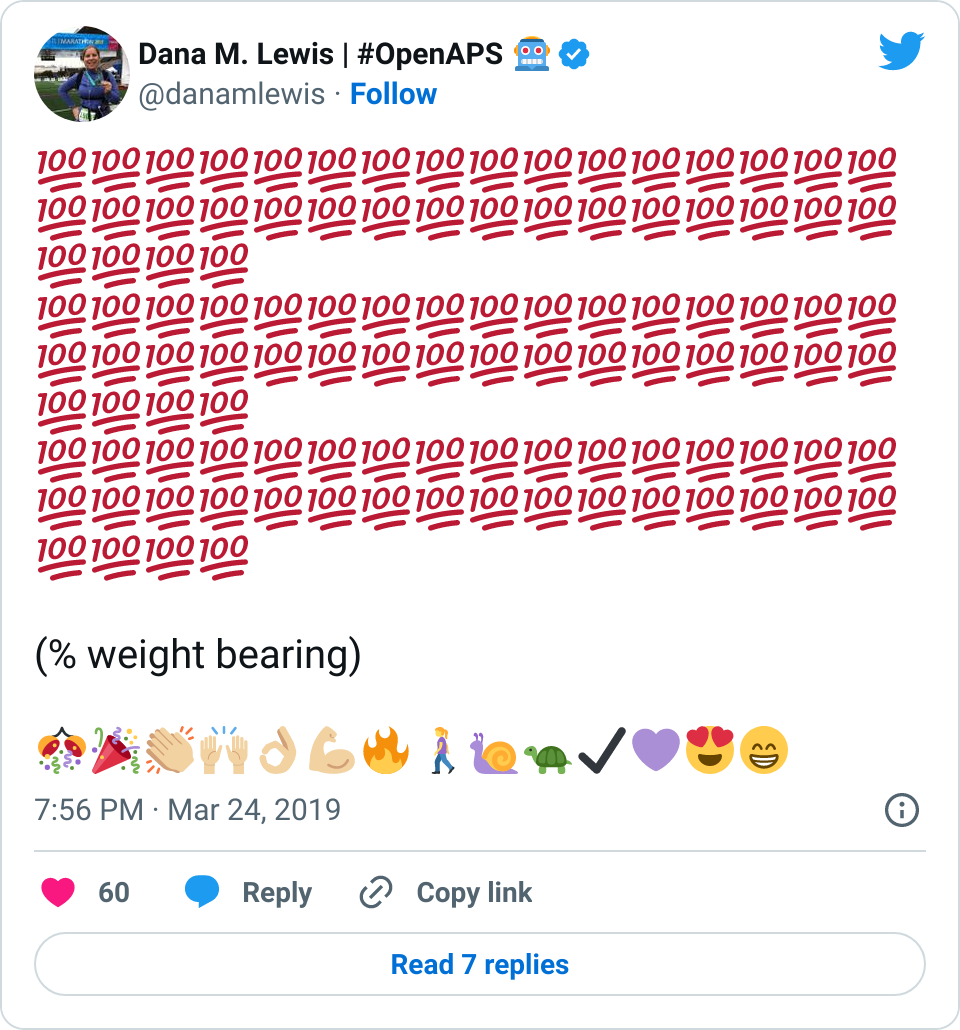

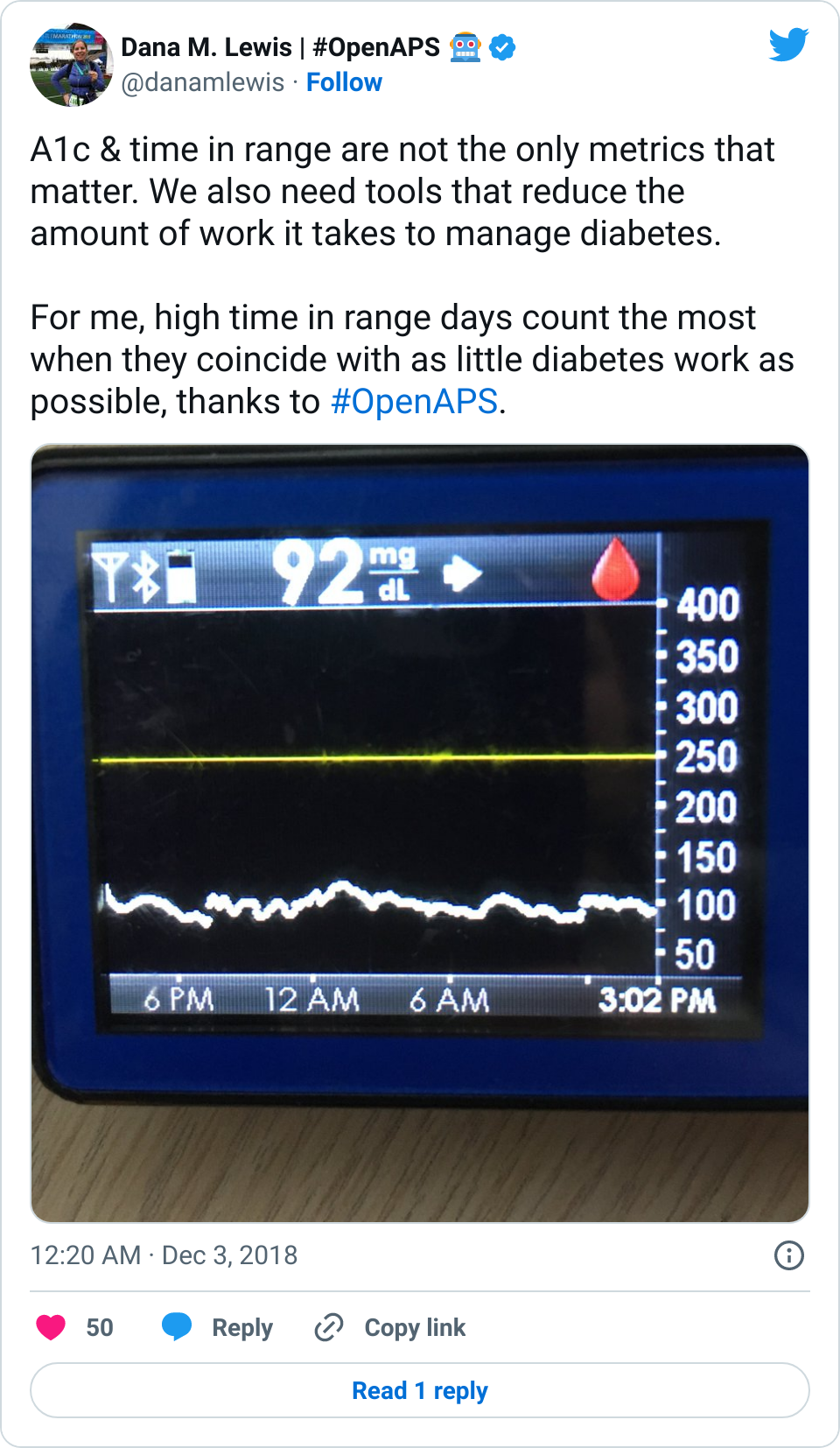

- Overall, while I was 100% non-weight bearing, I was eating slightly (but not much) lower carb and slightly less processed food than I usually do. But not always. One day I ended up having 205+ grams of carbs for me (quite a bit more than my average). However, thanks to #OpenAPS, I still managed to have a 100% in range day (80-150 mg/dL). Similarly on a travel day soon after, I ate a lot less (<50g carb) and also had a great day where OpenAPS took care of any surges and dips automatically – and more importantly, without any extra work and energy on my part. Having OpenAPS during the broken bone recovery has been a HUGE benefit, not only for keeping my BGs in range so much of the time for optimal healing, but also for significantly reducing the amount of work and cognitive burden it takes to stay alive with type 1 diabetes in general. I barely had energy to eat and do my hour of weight bearing each day, let alone anything else. Thankfully good BGs didn’t fall by the wayside, but without this tech it certainly would have.

And finally the pep talk I gave myself every day during weight bearing progression work:

This is short-term and necessary discomfort and suffering on the way to weight bearing. It sucks, but you can and will do it. You have to do it. If you need to take a break, take a break. If you need to do something else to get yourself pumped up and motivated to do your weight bearing, it’s ok to do that. But you’ll get there. Slowly, but surely. You’ve got this!

Proof that I did get there:

—

Best of luck and lots of support and encouragement to anyone who’s working their way to weight bearing after an injury, and many thanks to everyone who’s supported me and cheered me on virtually along the way!

2021 update – see this post about (finally) running the marathon that I had signed up for before I broke my ankle!

Recent Comments