Today I saw that Medtronic announced a partnership with IBM. You can read about it on Twitter, where I first saw it, or elsewhere online. There’s lots of news articles and PR about it, too, which I haven’t read yet in great detail.

My initial reaction:

Additional context:

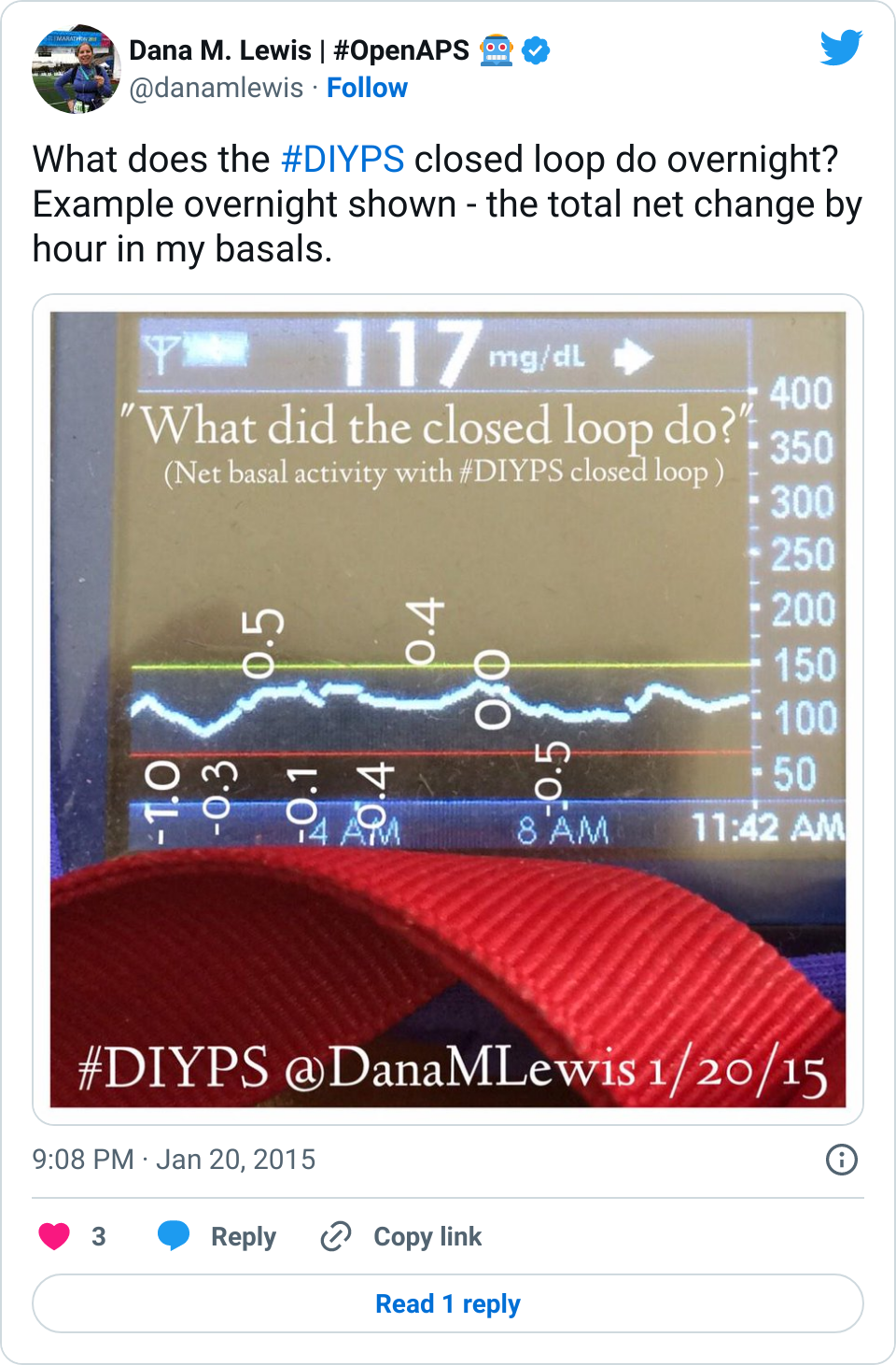

When I reduce my insulin (either by “suspending” the pump’s activity altogether, or by reducing my basal rate with a “temp” or temporary basal rate), there’s no record of it visible on my insulin pump.

None, at all.

Suspended for 15 minutes while I’m in the shower? No record of it if I accidentally resume insulin activity before checking to see when I suspended it.

Same for if I go running and activate a reduce basal rate (again, a “temp”) of 0.3u/hour instead of my usual 1.3/hour. That’s 1u less of insulin than I normally get. If I cancel it, or if that hour ends without me noticing it?

No record at all.

Which means if my blood glucose skyrockets an hour later, it will take me much longer to catch up with insulin if I don’t realize that I’m -1u (negative one unit) below what my body is used to.

Suspending your pump for 3 hours to go swimming? Same deal. Your body has less insulin than it’s used to, but you have to manually and mentally keep track of it.

The reverse is true as well – if you are sick and your body is more resistant to insulin than usual, and you use a higher basal rate than your usual as a way to additionally correct for a high BG?

No record of the additional insulin you’re putting into your body above your baseline basal profile.

THIS IS DANGEROUS.

And yet this is the FDA approved medical device that everyone is happy that I’m using? Even with critical flaws that endanger my life every day?

And the world has a problem with patients “hacking” or otherwise finding ways to access this critical data since we can’t get it from our approved devices?

This is backwards.

Medtronic and other pump brands track how much “insulin on board” (aka IOB) you have…but this number is wrong, because it doesn’t calculate the lack of insulin if you adjust your basal rates (examples above).

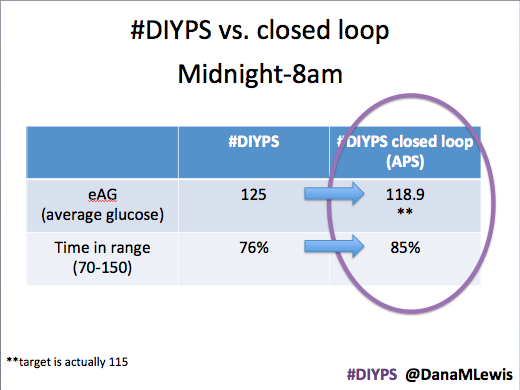

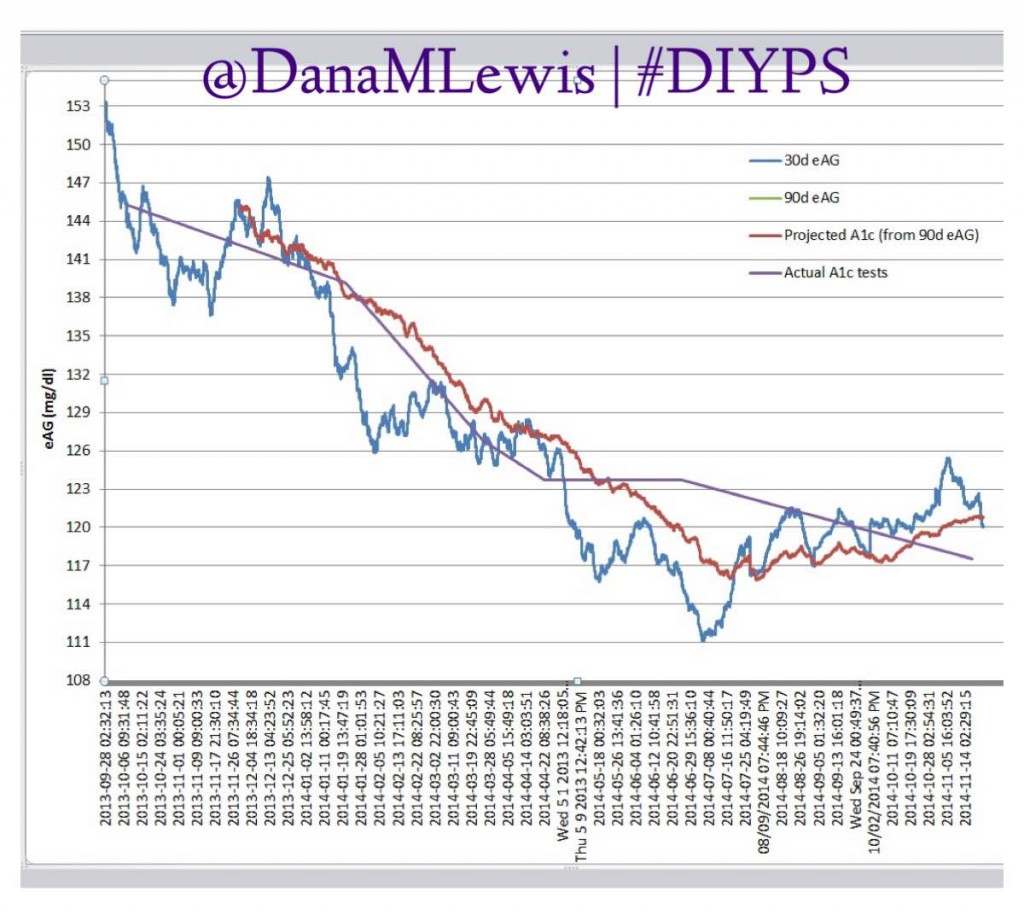

This is something I’ve been doing with #DIYPS to compensate for the inaccessibility of data from my FDA-approved medical device. Instead, I have to calculate for myself the “net” IOB number that takes into account any ‘negative’ corrections from suspending or negative or positive temp basal rates. These make a huge difference in my diabetes care.

We’ve learned from talking to people about #DIYPS for a year and a half that many people don’t use temporary basal rates, even though they’re very effective to ward off future lows and highs.

Why?

For one thing, it’s because there’s no record in their pumps. It’s too hard, and too much guesswork when there’s no record.

I don’t understand why the pump companies seem to ignore this. (If someone has a pump that tracks net IOB and/or shows a history of temporary basal rates and suspension, let me know. I’m familiar mainly with Medtronic’s pumps.)

This is not ok.

So while I think there’s a lot of potential for Medtronic to do more things with diabetes data (like this or this) through this partnership with IBM’s Watson? In the meantime, I’d like them to start with something much more simple – and with guaranteed impact.

Give me, the patient, my data that I need – directly on my medical device – so I can safely take care of myself and better manage my diabetes.

(Note – I realize FDA approval cycles on pumps take a long time, and this is unlikely to get fixed in current pumps. But future pumps? This should be fixed across the industry. And in the meantime? Companies can and should make it much easier to access data from the pumps via their approved uploader methods and make it easier to read the data. Right now, it’s not even easy to see the data off your pump. Let’s change this.)

Recent Comments