Being a raccoon loading a dishwasher is a really useful analogy for figuring out: what you want to spend a lot of effort and precision on, where you can lower your effort and precision and still obtain reasonable outcomes, or where you can allow someone else to step in and help you when you don’t care how as long as the job gets done.

Huh? Raccoons?!

A few years ago Scott and I spotted a meme/joke going around that in every relationship there is a person who loads the dishwasher precisely (usually “stacks the dishwasher like a Scandinavian architect”) and one who loads the dishwasher like a “raccoon on meth” or a “rabid raccoon” or similar.

Our relationship and personality with dishwasher loading isn’t as opposite on the spectrum as that analogy suggests. However, Scott has a strong preference for how the dishwasher should be loaded, along with a high level of precision in achieving it. I have a high level of precision, but very low preference for how it gets done. Thus, we have evolved our strategy where I put things in and he re-arranges them. If I put things in with a high amount of effort and a high level of precision? He would rearrange them ANYWAY. So there is no point in me also spending high levels of effort to apply a first style of precision when that work gets undone. It is more efficient for me to put things in, and then he re-organizes as he sees fit.

Thus, I’ve embraced being the ‘raccoon’ that loads the dishwasher in this house. (Not quite as dramatic as some!)

This came to mind because he went on a work trip, and I stuck things in the dishwasher for 2 days, and jokingly texted him to “come home and do the dishes that the raccoon left”. He came home well after dinner that night, and the next day texted when he opened the dishwasher for the first time that he “opened the raccoon cage for the first time”. (LOL).

This came to mind because he went on a work trip, and I stuck things in the dishwasher for 2 days, and jokingly texted him to “come home and do the dishes that the raccoon left”. He came home well after dinner that night, and the next day texted when he opened the dishwasher for the first time that he “opened the raccoon cage for the first time”. (LOL).

Over the years, we’ve found other household tasks and chores where one of us has strong preferences about the way things should be done and the other person has less strong preferences. Similarly, there are some things that feel high-effort (and not worth it) for one of us but not the other. Over time, we’ve sorted tasks so things that feel high-effort can be done by the person for which it doesn’t feel high-effort, and depending on the preference level determines ‘how’ it gets done. But usually, the person who does it (because it’s low-effort) gets to apply their preferences, unless it’s a really weak preference and the preference of the non-doer doesn’t require additional effort.

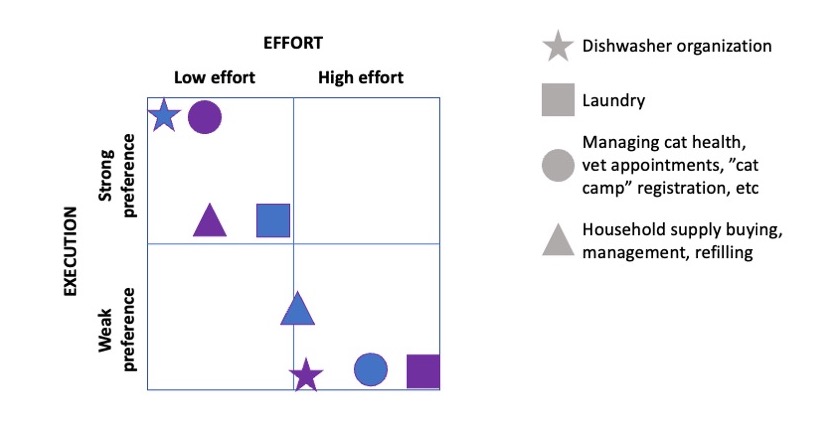

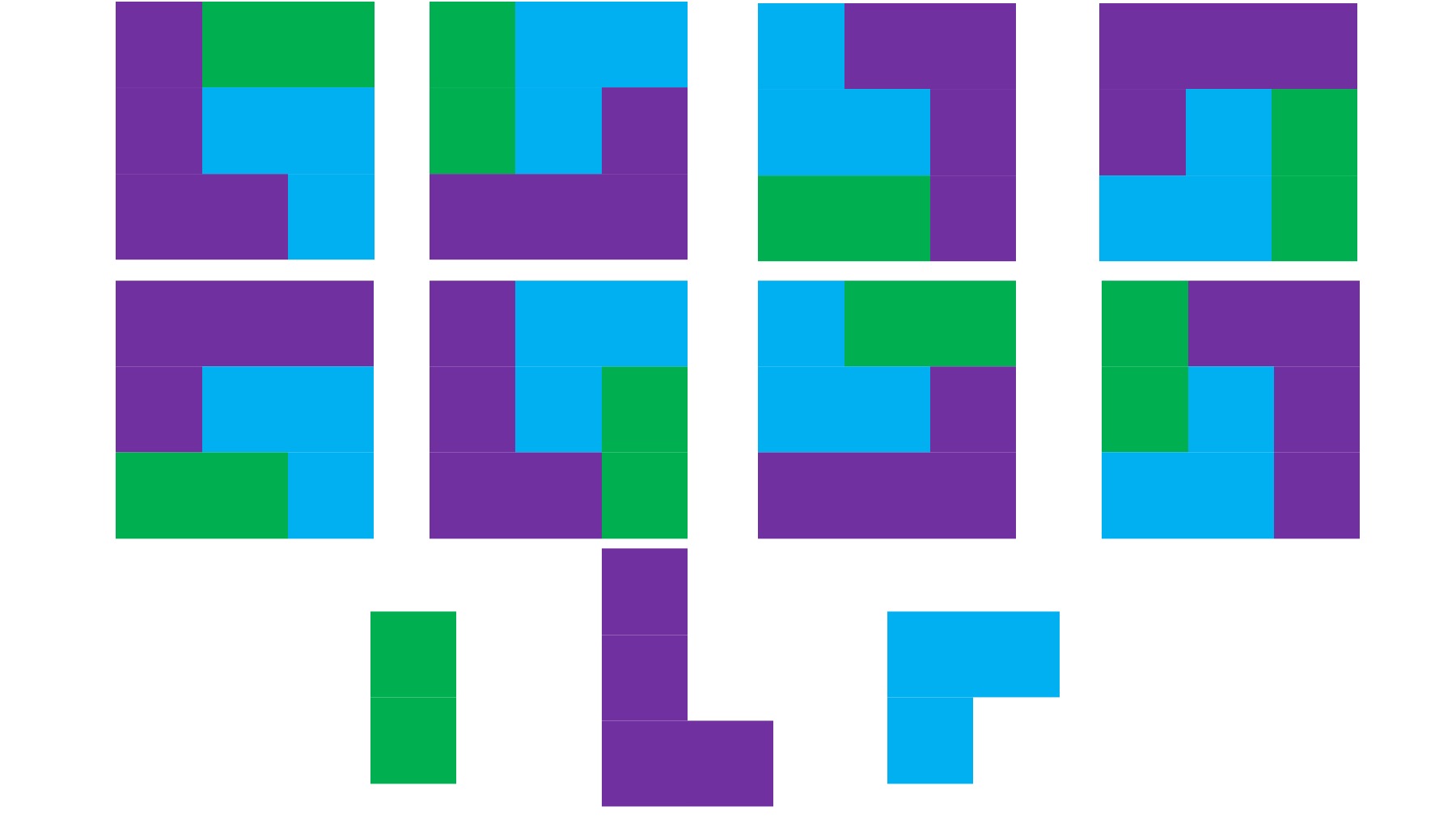

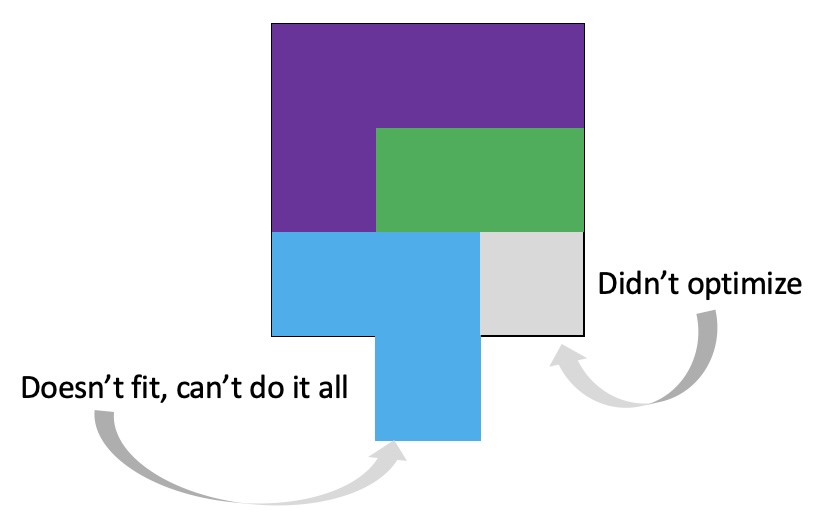

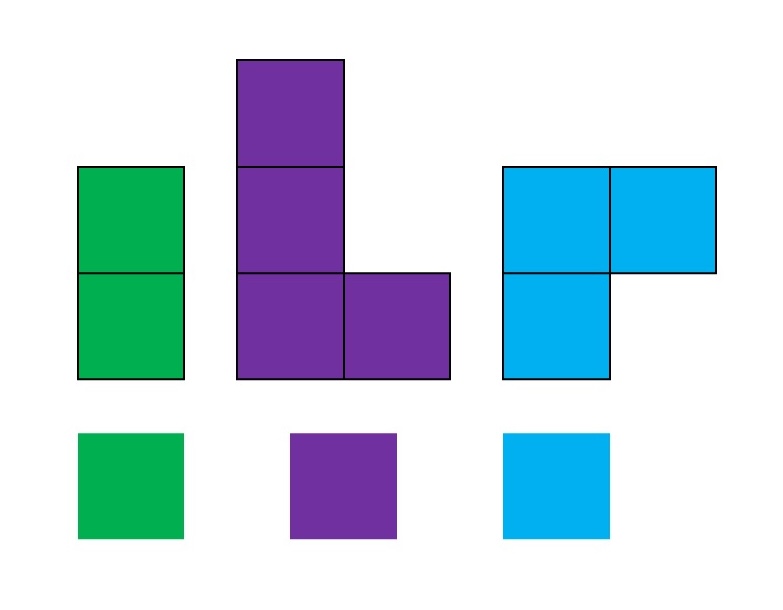

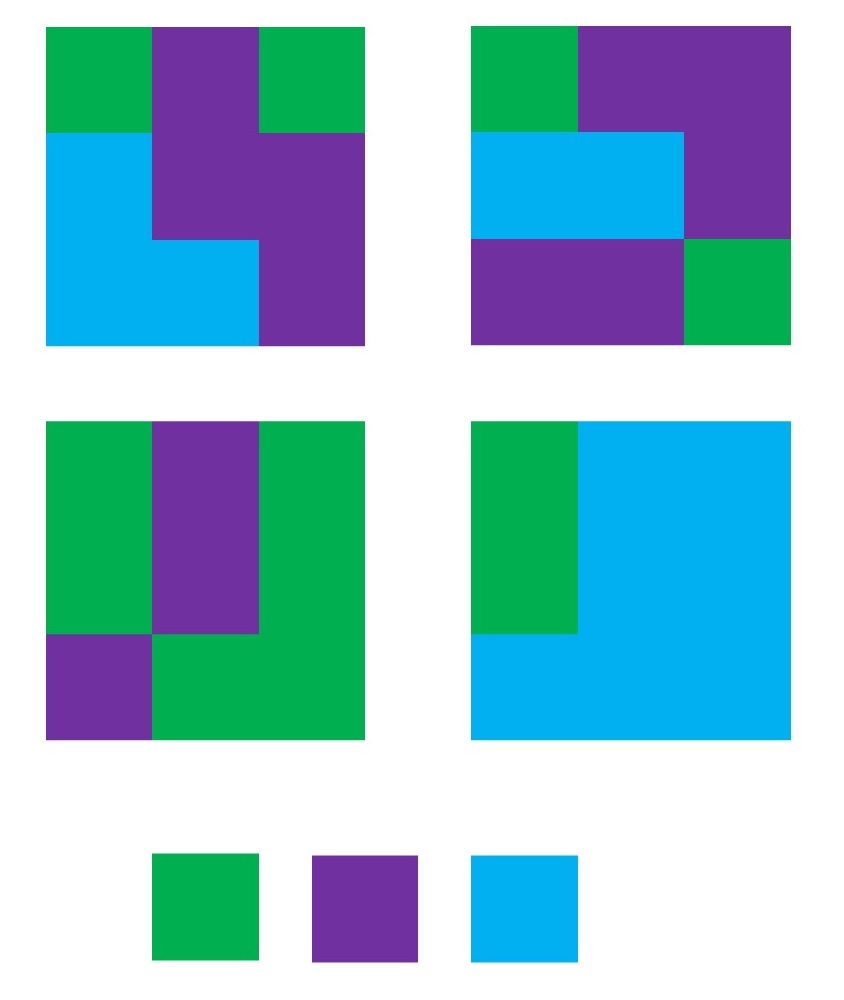

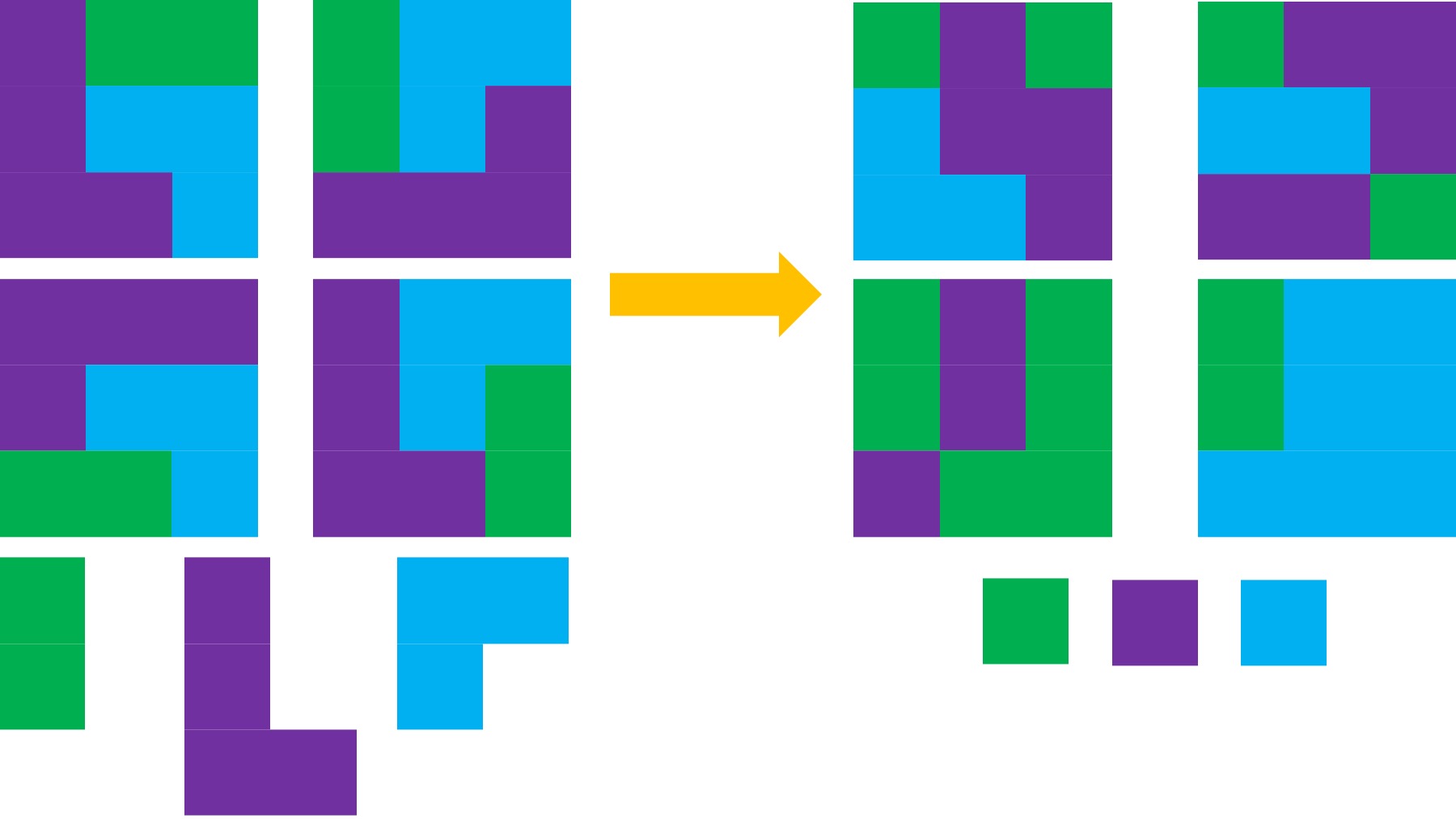

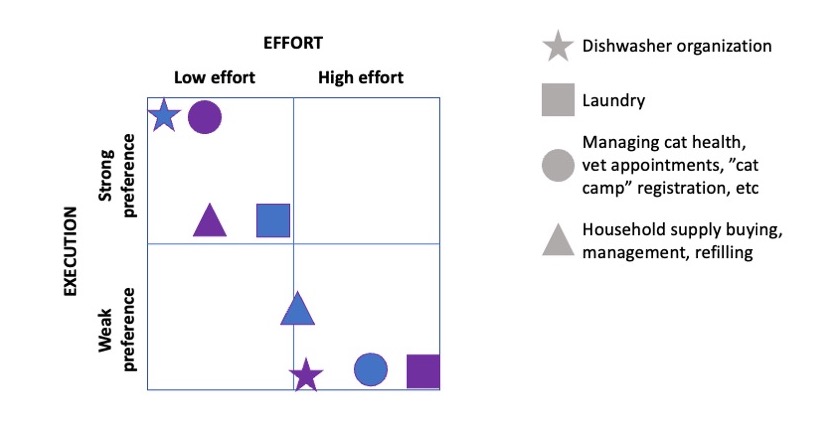

Here are some examples of tasks and how our effort/preference works out. You can look at this and see that Scott ends up doing the dishwasher organization (after I load it like a raccoon) before starting the dishwasher and also has stronger preferences about laundry than I do. On the flip side, I seem to find it easier with routines for staying on top of household supply management including buying/re-ordering and acquiring and putting those away where we have them ready to go, because they’re not on a clear scheduled cadence. Ditto for managing the cats’ health via flea/tick medication schedules, scheduling and taking them to the vet, signing them up for cat camp when we travel, coordinating with the human involved in their beloved cat camp, etc. We end up doing a mix of overall work, split between the two of us.

Could each of us do those tasks? Sure, and sometimes we do. But we don’t have to each do all of them, all the time, and we generally have a split list of who does which type of things as the primary doer.

Raccoons and burnout with chronic diseases

I have now lived with type 1 diabetes for almost 22 years. When I met Scott, I had been living with diabetes for 11 years. When he asked on one of our early dates what he could do to help, my answer was: “…nothing?” I’m an adult, and I’ve successfully managed my diabetes solo for decades.

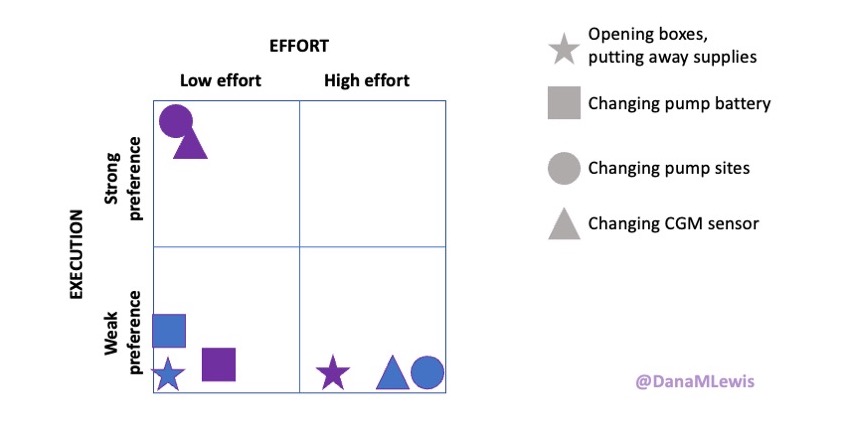

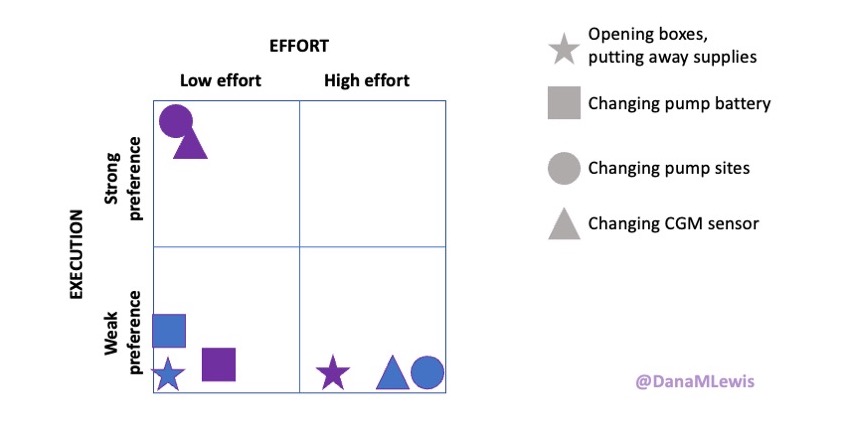

Obviously, we ended up finding various ways for him to help, starting with iterating together on technological solutions for remote monitoring (DIYPS) to eventually closing the loop with an automated insulin delivery system (OpenAPS). But for the longest time, I still did all the physical tasks of ordering supplies, physically moving them around, opening them, managing them, etc. both at a 3-month-supply order level and also every 3 days with refilling reservoirs and changing pump sites and sensors.

Most of the time, these decades-long routines are literally routines and I do them without thought, the same way I put on my shoes before I leave the house. Yet when burnout is approaching – often from a combination of having five autoimmune diseases or having a lot of life going on while also juggling the ‘routine’ tasks that are voluminous – these can start to feel harder than they should.

Should, being the key word here.

Scott would offer to do something for me and I would say no, because I felt like I “should” do it because I normally can/am able to with minimal effort. However, the activation energy required (because of burnout or volume of other tasks) sometimes changes, and these minimal, low-effort tasks suddenly feel high-effort. Thus, it’s a good time to examine whether someone can – even in the short term and as a one-off – help.

It’s hard, though, to eradicate the “should”. I “should” be able to do X, I “should” be able to handle Y. But honestly? I should NOT have to deal with all the stuff and management of living with 5 autoimmune diseases and juggling them day in and day out. But I do have to deal with these and therefore do these things to stay in optimal health. “Should” is something that I catch myself thinking and now use that as a verbal flag to say “hey, just because I CAN do this usually doesn’t mean I HAVE to do it right now, and maybe it’s ok to take a break from always doing X and let Scott do X or help me with Y.”

Some of these “I should do it” tasks have actually become tasks that I’ve handed off long-term to Scott, because they’re super low effort for him but they’re mildly annoying for me because I have roughly 247 other tasks to deal with (no, I didn’t count them: that would make it 248).

For example, one time I asked him to open my shipment with 3 months worth of pump supplies, and unbox them so I could put them away. He also carried them into the room where we store supplies and put them where they belonged. Tiny, but huge! Only 246 tasks left on my list. Now, I order supplies, and he unboxes and puts them away and manages the inventory rotation: putting the oldest boxes on top (that I draw from first) and newer ones on bottom. This goes for pump supplies, CGM supplies, and anything else mail order like that.

This isn’t always as straightforward, but there are a lot of things I have been doing for 20+ years and thus find very low effort once the supplies are in my hand, like changing my pump site and CGM. So I do those. (If I was incapacitated, I have no doubt Scott could do those if needed.) But there’s other stuff that’s low effort and low preference like the opening of boxes and arranging of supplies that I don’t have to do and Scott is happy to take on to lower my task list of 247 things so that I only have about 240 things left to do for routine management.

Can I do them? Sure. Should I do them? Well, again, I can but that doesn’t mean I have to if there’s someone who is volunteering to help.

And sometimes that help is really useful in breaking down tasks that are USUALLY low effort – like changing a pump site – but become high effort for psychological reasons. Sometimes I’ll say out loud that I need to change my pump site, but I don’t want to. Some of that might be burnout, some of that is the mental energy it takes to figure out where to put the next pump site (and remembering the last couple of placements from previous sites, so I rotate them), combined with the physical activation energy to get up from wherever I am and go pull out the supplies to do it. In these cases, divide and conquer works! Scott often is more than happy to go and pull out a pump site and reservoir and place it where it’s convenient for me when I do get up to go do something else. For me, I often do pump site changes (putting a new one on, but I keep the old one on for a few extra hours in case the new one works) after my shower, so he’ll grab a pump site and reservoir and set it on the bathroom counter. Barrier removed. Then I don’t have to get up now and do it, but I also won’t forget to do it because it’s there in flow with my other tasks to do after my shower.

There are a lot of chronic disease-related tasks like this that when I’m starting to feel burnout from the sheer number of tasks, I can look for (or sometimes Scott can spot) opportunities) to break a task into multiple steps and do them at different times, or to have someone do the task portions they can do, like getting out supplies. That then lowers the overall effort required to do that task, or lowers the activation energy depending on the task. A lot of these are simple-ish tasks, like opening something, getting something out and moving it across the house to a key action spot (like the bathroom counter for after a shower), or putting things away when they no longer need to be out. The latter is the raccoon-style approach. A lot of times I’ll have the activation energy to start and do a task, but not complete (like breaking down supply boxes for recycling). I’ll set them aside to do later, or Scott will spot this ‘raccoon’ stash of tasks and tackle it when he has time/energy, usually faster than me getting around to do it because he’s not burdened with 240 other tasks like that. (He does of course have a larger pile of tasks than without this, but the magnitude of his task list is a lot smaller, because 5 autoimmune diseases vs 0.)

Be a friend to your friend who needs to be a raccoon some of the time

I am VERY lucky to have met & fallen in love & married someone who is so incredibly able and willing to help. I recognize not everyone is in this situation. But there may be some ways our friends and family who don’t live with us can help, too. I had a really fantastic example of this lately where someone who isn’t Scott stepped up and made my raccoon-life instantly better before I even got to the stage of being a raccoon about it.

I have a bunch of things going on currently, and my doctor recommended that I have an MRI done. I haven’t had an MRI in years and the last one was pre-pandemic. Nowadays, I am still masking in any indoor spaces including healthcare appointments, and I plan to mask for my MRI. But my go-to n95 mask has metal in the nose bridge, which means I need to find a safe alternative for my upcoming MRI.

I was busy trying to schedule appointments and hadn’t gotten to the stage of figuring out what I would wear as an alternative for my MRI. But I mentioned to a friend that I was going to have an MRI and she asked what mask I was going to wear, because she knows that I mask for healthcare appointments. I told her I hadn’t figured it out yet but needed to eventually figure it out.

She instantly sprang into action. She looked up options for MRI-safe masks and asked a local friend who uses a CAN99 mask without wire whether the friend had a spare for me to try. She also ordered a sample pack of another n95 mask style that uses adhesive to stick to the face (and thus doesn’t have a metal nose bridge piece). She ordered these, collected the CAN99 from the local friend, and then told me when they’d be here, which was well over a week before I would need it for the MRI and offered to bring them by my house so I had them as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, I was gobsmacked with relief and appreciation because I would have been a hot mess of a raccoon trying to get around to sorting that out days or a week after she had sorted a variety of options for me to try. Instead, she predicted my raccoon-ness or otherwise was being a really amazing friend and stepping up to take something off my plate so I had one less thing to deal with.

Yay for helpers. In this case, she knew exactly what was needed. But a lot of times, we have friends or family who want to help but don’t know how to or aren’t equipped with the knowledge of what would be helpful. Thus, it’s useful – when you have energy – to think through how you could break apart tasks and what you could offer up or ask as a task for someone else to do that would lower the burden for you.

That might be virtual tasks or physical tasks:

- It might be coming over and taking a bunch of supplies out of boxes (or medicine) and splitting them up and helping put them in piles or all the places those things need to go

- It could be researching safe places for you to eat, if you have food allergies or restrictions or things like celiac

- It could be helping divvy up food into individual portions or whatever re-sizing you need for whatever purpose

- It could be researching and brainstorming and identifying some safe options for group activities, e.g. finding places with outdoor dining or cool places to walk and hike that suits everyone’s abilities and interests

Sometimes it’s the physical burden that it’s helpful to lift; sometimes it’s the mental energy burden that is helpful to lift; sometimes a temporary relief in all the things we feel like we have to do ourselves is more important than the task itself.

If you have a chronic disease, it’s ok to be a raccoon. There is no SHOULD.

Part of the reason I really like the raccoon analogy is because now instead of being annoyed at throwing things in the dishwasher, because whether I exert energy or not Scott is going to re-load it his way anyway, I put the dishes in without much precision and giggle about being a raccoon.

The same goes for chronic disease related-tasks. Even for tasks where Scott is not involved, but I’m starting to feel annoyed at something I need to do, I find ways to raccoon it a little bit. I change my pump site but leave the supplies on the counter because I don’t HAVE to put those away at the same moment. I usually do, but I don’t HAVE to. And so I raccoon it a bit and put the supplies away later, because it doesn’t hurt anyone or anything (including me) for those not to get put away at the same time. And that provides a little bit of comedic relief to me and lightens the task of changing my pump site.

It also helps me move away from the SHOULD weighing heavily in my brain. I should be able to get all my pump site stuff out, change it, and throw away and put away the supplies when done. It shouldn’t be hard. No one else has this challenge occasionally (or so my brain tells me).

But the burden isn’t about that task alone. It’s one task in the list of 247 things I’m doing every day to take care of myself. And sometimes, my list GROWS. January 18, my list was about 212 things I needed to do. Beginning January 19, my list jumped up to 230. Last week, it grew again. I have noticed this pattern that when my list of things to do grows, some of the existing “easy” tasks that I’ve done for 20 years suddenly feel hard. Because it is hard to split my energy across more tasks and more things to focus on; it takes time to adapt. And so being a raccoon for some of those tasks, for some of the time, provides a helpful steam-valve to output some of the challenges I’m juggling of dealing with all the tasks, because those tasks 100% don’t have to be done in the same way as I might do during “calm” static times where my task list hasn’t expanded suddenly.

And it doesn’t matter what anyone else does or what they care about. Thus, remove the should. You should be able to do this, sure – if you weren’t juggling 246 other things. But you do have 246 things and that blows apart the “should”.

Free yourself of the “should” wherever possible, and be a raccoon wherever it helps.

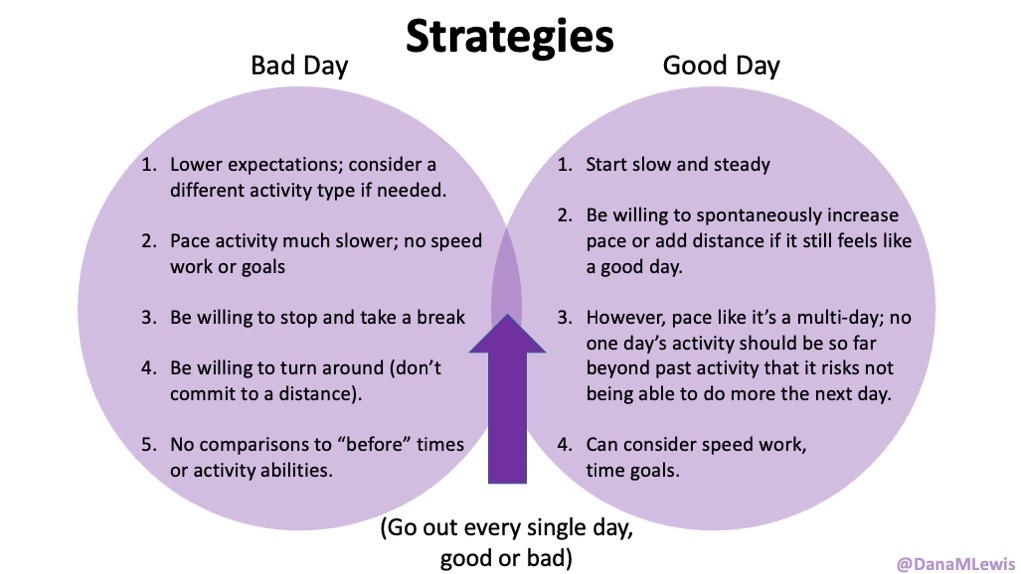

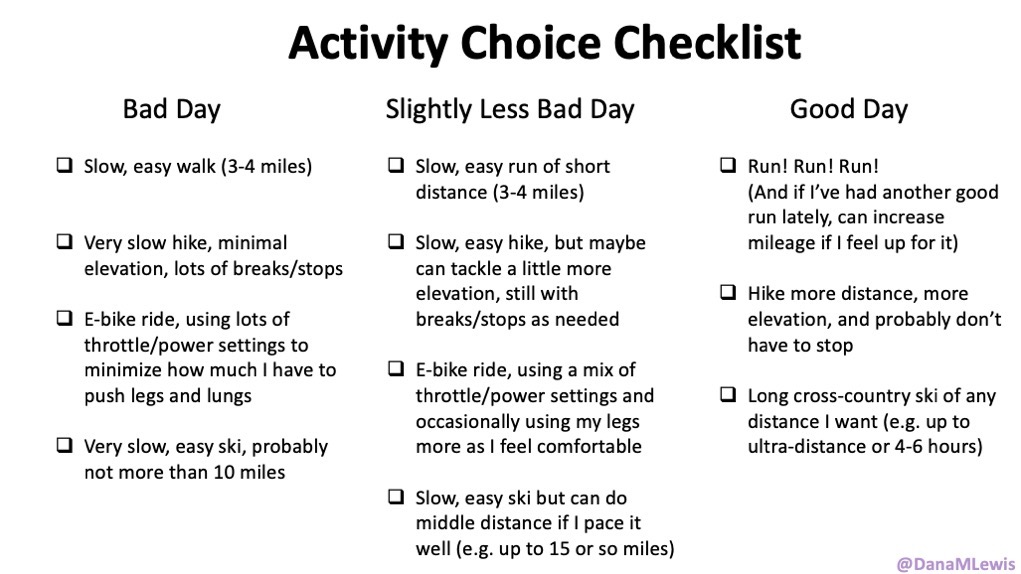

As things change in my body (I have several autoimmune diseases and have gained more over the years), my ‘budget’ on any given day has changed, and so have my priorities. During times when I feel like I’m struggling to get everything done that I want to prioritize, it sometimes feels like I don’t have enough energy to do it all, compared to other times when I’ve had sufficient energy to do the same amount of daily activities, and with extra energy left over. (Sometimes I feel like a raccoon juggling three spoons of different weights.)

As things change in my body (I have several autoimmune diseases and have gained more over the years), my ‘budget’ on any given day has changed, and so have my priorities. During times when I feel like I’m struggling to get everything done that I want to prioritize, it sometimes feels like I don’t have enough energy to do it all, compared to other times when I’ve had sufficient energy to do the same amount of daily activities, and with extra energy left over. (Sometimes I feel like a raccoon juggling three spoons of different weights.)

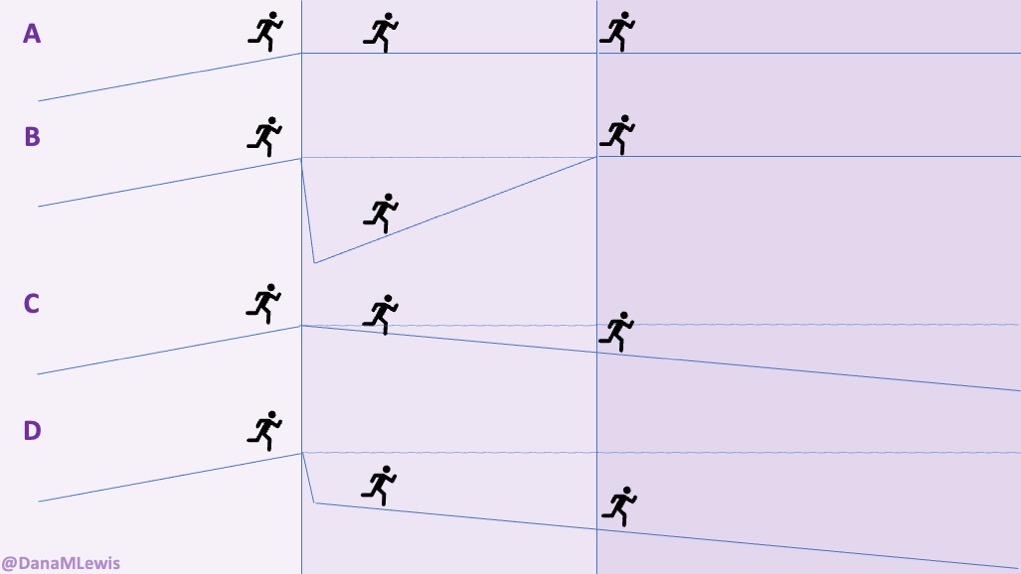

It’s important to remember that even if the total amount of time is “a lot”, it doesn’t have to be done all at once. Historically, a lot of us might work 8 hour days (or longer days). For those of us with desk jobs, we sometimes have options to split this up. For example, working a few hours and then taking a lunch break, or going for a walk / hitting the gym, then returning to work. Instead of a static 9-5, it may look like 8-11:30, 1:30-4:30, 8-9:30.

It’s important to remember that even if the total amount of time is “a lot”, it doesn’t have to be done all at once. Historically, a lot of us might work 8 hour days (or longer days). For those of us with desk jobs, we sometimes have options to split this up. For example, working a few hours and then taking a lunch break, or going for a walk / hitting the gym, then returning to work. Instead of a static 9-5, it may look like 8-11:30, 1:30-4:30, 8-9:30.

(Thank you).

(Thank you).

This basically has been our plan for if either of us were to get COVID-19 (or the flu), and it’s good to know this plan works for a variety of conditions including RSV and the common cold. The main thing we would do differently in the future is that Scott should have masked the very first night he had symptoms of RSV, and he has decided that he’ll be masking any time he’s in the same room as someone who’s been coughing, as that’s considerably less annoying than being sick. (He really did not like the experience of having RSV.) I obviously did not get it from that first night when he first had the most minor symptoms of RSV, but that was probably the period of highest risk of transmission of either week, given the subsequent precautions we took after that.

This basically has been our plan for if either of us were to get COVID-19 (or the flu), and it’s good to know this plan works for a variety of conditions including RSV and the common cold. The main thing we would do differently in the future is that Scott should have masked the very first night he had symptoms of RSV, and he has decided that he’ll be masking any time he’s in the same room as someone who’s been coughing, as that’s considerably less annoying than being sick. (He really did not like the experience of having RSV.) I obviously did not get it from that first night when he first had the most minor symptoms of RSV, but that was probably the period of highest risk of transmission of either week, given the subsequent precautions we took after that.

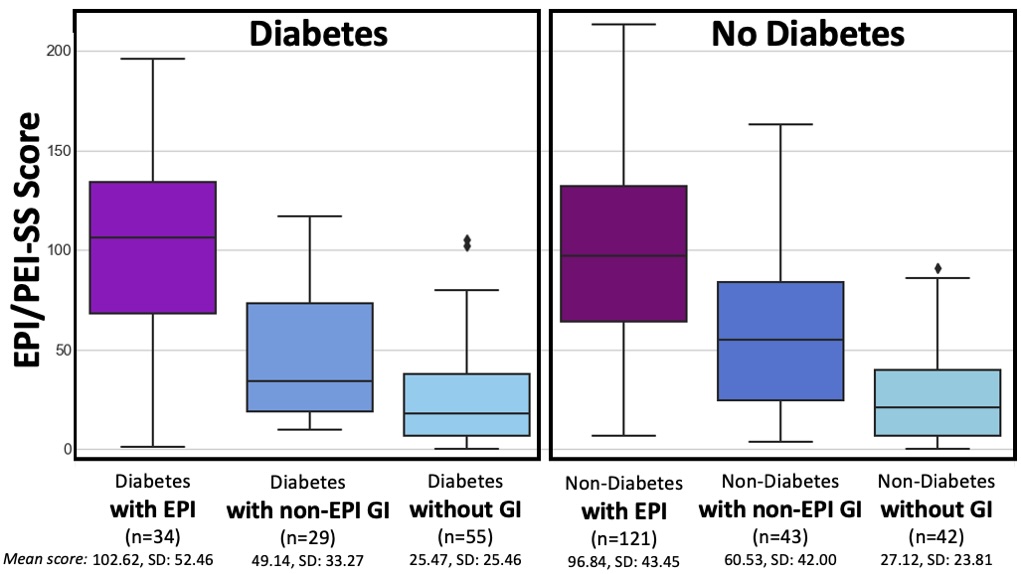

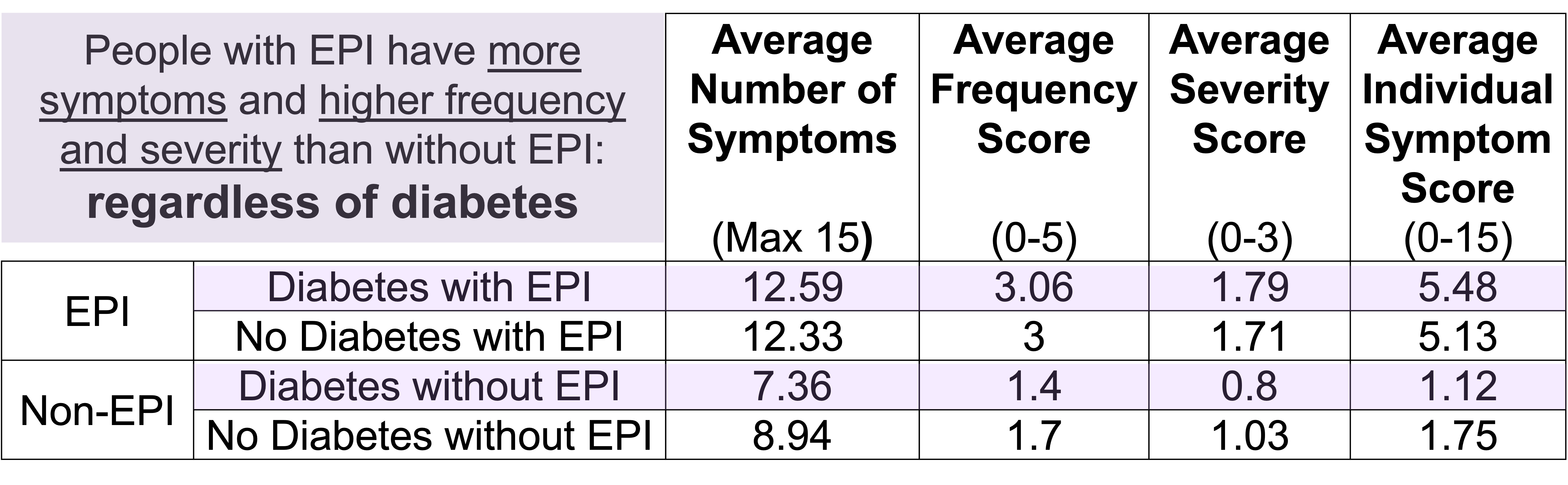

How do you have people take the EPI/PEI-SS? You can pull this link up (

How do you have people take the EPI/PEI-SS? You can pull this link up ( This came to mind because he went on a work trip, and I stuck things in the dishwasher for 2 days, and jokingly texted him to “come home and do the dishes that the raccoon left”. He came home well after dinner that night, and the next day texted when he opened the dishwasher for the first time that he “opened the raccoon cage for the first time”. (LOL).

This came to mind because he went on a work trip, and I stuck things in the dishwasher for 2 days, and jokingly texted him to “come home and do the dishes that the raccoon left”. He came home well after dinner that night, and the next day texted when he opened the dishwasher for the first time that he “opened the raccoon cage for the first time”. (LOL).

Recent Comments