I had the awesome opportunity to present at #AADE17, the annual education meeting for the American Association of Diabetes Educators, this past weekend. My topic was about OpenAPS and DIY diabetes… which really translates to some broader things I want all educators and HCPs to know about patients and technology, whether it’s DIY or just unknown to them. Unfortunately AADE didn’t record or livestream my session, so I wanted to write up a summary of the content here.

(If you’re new to this blog/me/OpenAPS, you can also watch this June 2017 TEDX talk where I share some of the story of how I ended up with a DIY artificial pancreas and how the OpenAPS community came to be; or this older talk from OSCON 2016 as well. As always, if you’re curious to learn more about OpenAPS or wondering how to build your own DIY artificial pancreas, OpenAPS.org is the first place to learn more!)

—

Diabetes is hard. Even if you are privileged to have access to insulin, education, and technology – it can still be so incredibly hard to get it right. And even if you do everything “right”, the outcomes will still vary. And after all, the devices themselves are not perfect, and we still have diabetes.

The lack of varying alarms and the unchangeable volume is what led me to create DIYPS (my open loop and louder alarm system), and the same frustration with lack of data access and visualization led John Costik, Lane Desborough, Ben West, and so many others to explore creating other DIY tools, such as Nightscout. And thanks to social media, we all didn’t have to create in a vacuum: we can share code (this is what open source means) and insight through social media, and build upon each other’s work. As a result, these collaborations, sharing, and iterative development is how OpenAPS, the open source artificial pancreas system movement, was created.

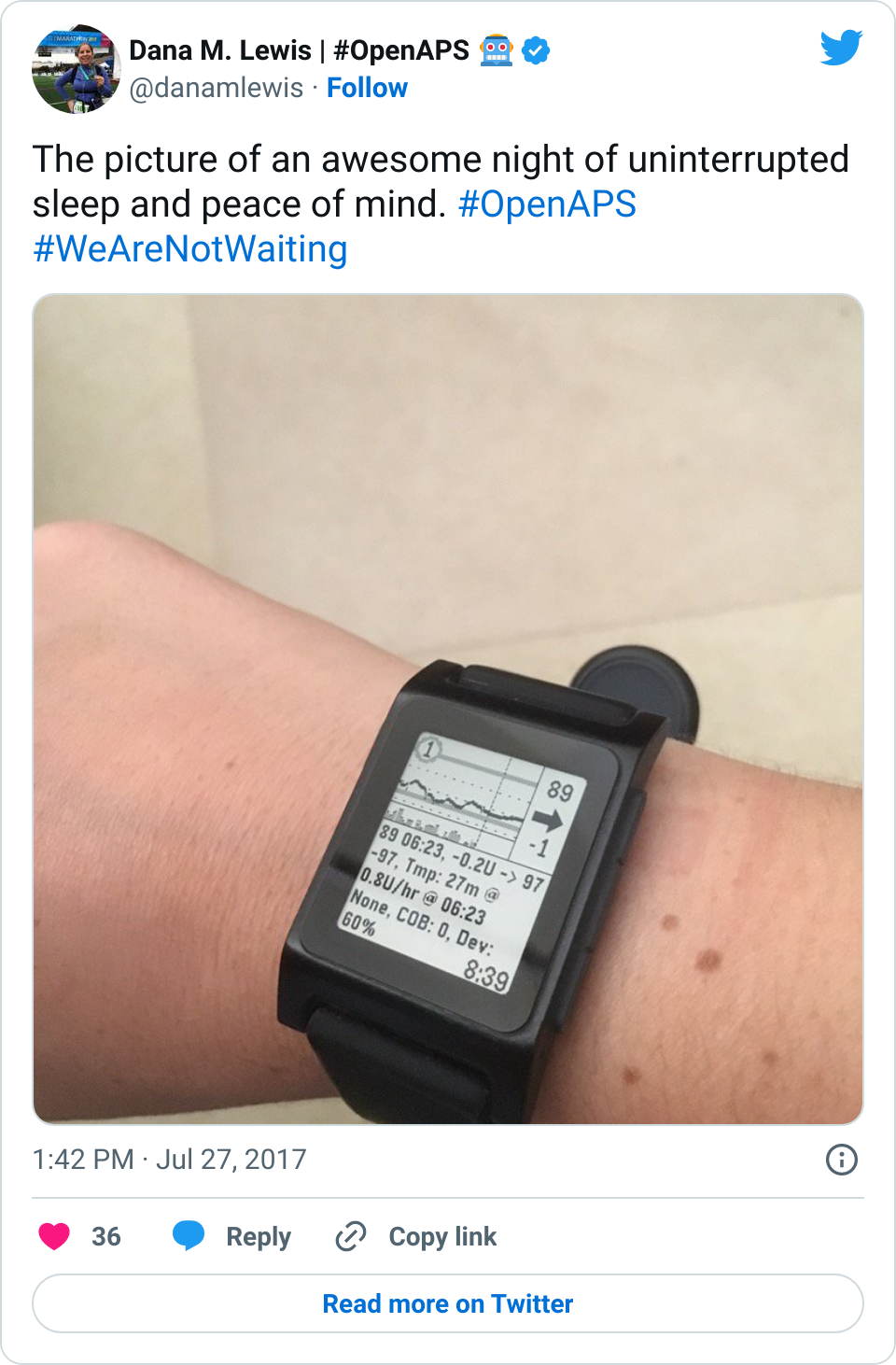

I tweet and talk and share frequently about how great it is having #OpenAPS in my life. Norovirus? No problem. Changes in sensitivity due to exercise? Not the biggie it used to be.

However, this technology is by no means a cure. It still requires work on the part of the person with diabetes. We still have to:

- Change pump sites

- Change CGM sensors

- Calibrate regularly

- Deal with bonked pump sites and sensors that fall out

And also, given the speed of insulin, most people are still going to engage with the system for some kind of meal bolus or announcement. This is why it’s called “hybrid” closed loop technology. (However, depending on the sophistication of the technology, you start to get to be able to choose what you want to optimize for and the behaviors you want to choose to do less of, which is great.)

In some cases, we humans know more than the technology: such as when a meal is going to happen/is coming, and when exercise is going to happen. So it’s nice to be able to interoperate your devices and be able to use your phone, watch, computer, etc. to be able to tell the system what to do differently (i.e. set higher targets in the case of activity, or lower targets to achieve “eating soon” mode , or in the case of waking up).

But in a LOT of cases, it’s tiring for the human to have to think about all the things. Such as whether a pump site is slowly dying and causing apparent insulin resistant. Or such as when you’re more sensitive 12-24 hours after exercise. Or during menstrual cycles. Or when sick. Or during a growth spurt. Or during jet lag. Or during a trip where you can’t find anything to eat. Etc. It’s a lot for us PWD’s to track, and this is where computers come in handy. Things like autosensitivity in OpenAPS to automatically detect changes in sensitivity and adjust the variables for calculations automatically; and autotune, to track the data of what’s actually happening and make recommendations for changing your underlying pump settings (ISF, carb ratio, and basal rates).

And how has this technology been developed by patients? Iteratively, as we figure out what’s possible. It’s not about boiling the ocean; it’s about approaching problems bit by bit as we have new tools to solve them, or new people with energy to think about the problem in different ways. It’s like thinking about getting a car – you wouldn’t expect the manufacturer to sell bits and pieces of the car frame, and you don’t really expect medical device manufacturers to sell bits and pieces of a pump or other device. However, patients are closest to the REAL problems in living with diabetes. Instead of a “car”, they’re looking for solutions for getting from point A to point B. And so in the car analogy, that means starting with a skateboard, scooter, or bike – and ending up with a car is great, but the car is not the point.

. @Danamlewis shares awesome visual analogy for #wearenotwaiting movement- using #diabetes tools we have NOW #AADE17 pic.twitter.com/HrtVlsnL1g

— DiabetesMine (@DiabetesMine) August 5, 2017

So no, any piece of technology isn’t going to be a cure or solve all problems or work perfectly for everyone. But that is true whether it’s DIY or a commercial tool: one size certainly does not fit all. And patients are individuals with their own lives and their own challenges with diabetes, with different motivations around what aspects of life with diabetes feel like friction and what they feel equipped to tackle and solve.

So, here’s some of what’s on my list for what I’d like CDE’s and other HCP’s to know as a result of the proliferation of technology around diabetes:

- Yes, DIY tech is often off label. But that’s ok – it just means it’s off label; it doesn’t prevent you from listening to why patients are using it, what we think it’s doing for us, and it doesn’t prevent you from asking questions, learning more, or still advising patients.

- Don’t make us switch providers by refusing to discuss it or listen to it, just because it’s new/different/you don’t understand it. (By the way: we don’t expect you to understand all possible technology! You can’t be experts on everything, but that doesn’t mean shunning what you don’t know.)

- You get to take advantage of the opportunity when someone brings something new into the office – it’s probably the first of many times you’ll see it, and the first patient is often on the bleeding edge and deeply engaged and understands what they’re using, and open to sharing what they’ve learned to help you, so you can also help other patients!

- You also get to take advantage of the open source community. It’s open, not just for patients to use, but for companies, and for CDEs and other HCPs as well. There are dozens if not hundreds of active people on Twitter, Facebook, blogs, forums, and more who are happy to answer questions and help give perspective and insight into why/how/what things are.

- Don’t forget – many of the DIY tools provide data and insight that currently don’t exist in any traditional and/or commercially and/or FDA-approved tool. Take autotune for example – there’s nothing else out there that we know of that will tune basal rates, ISF, and carb ratio for people with pumps. And the ability of tools like Nightscout reports to show data from a patient’s disparate devices is also incredibly helpful for healthcare providers and educators to use to help patients.

And one final point specific to hybrid closed loop technology: this technology is going to solve a lot of problems and frustrations. But, it may mean that patients will shift the prioritization of other quality of life factors like ease of use over older, traditionally learned diabetes behaviors. This means things like precise carb counting may go by the wayside for general meal size estimations, because the technology yields similar outcomes. Being aware of this will be important for when CDE’s are working with patients; knowing what the patterns of behaviors are and knowing where a patient has shifted their choices will be helpful for identifying what behaviors can be adapted to yield different outcomes.

—

I think the increase in technology (especially various types of closed loops, DIY and commercial) will yield MORE work for CDE’s and HCP’s, rather than less. This means it’s even more important for them to get up to speed on current and evolving technology – because it’s by no means going away. And the first wave of DIY’ers have a lot we can share and teach not just other patients, but also CDE’s. So again, many thanks to AADE for the opportunity to share some of this perspective at #AADE17, and thanks to everyone for the engagement during and after the session!

Thank you Dana for this, I’ve been looping for a few weeks now and I’m about to let my team know about it. I feel this article will be helpfull in the process.

Thank you for EVERYTHING you do, so grateful!