It’s been a busy couple (ok, more than couple) of months since we last blogged here related to developments from #DIYPS and #OpenAPS. (For context, #DIYPS is

Dana’s personal system that started as a louder alarms system and evolved into an open loop and then closed loop (

background here). #OpenAPS is the open source reference design that enables anyone to build their own DIY closed loop artificial pancreas. See

www.OpenAPS.org for more about that specifically.)

We’ve instead spent time spreading the word about OpenAPS in other channels (in the Wall Street Journal; on WNYC’s Only Human podcast; in a keynote at OSCON, and many other places like at the White House), further developing OpenAPS algorithms (incorporating “eating soon mode” and temporary targets in addition to building in auto-sensitivity and meal assist features), working our day jobs, traveling, and more of all of the above.

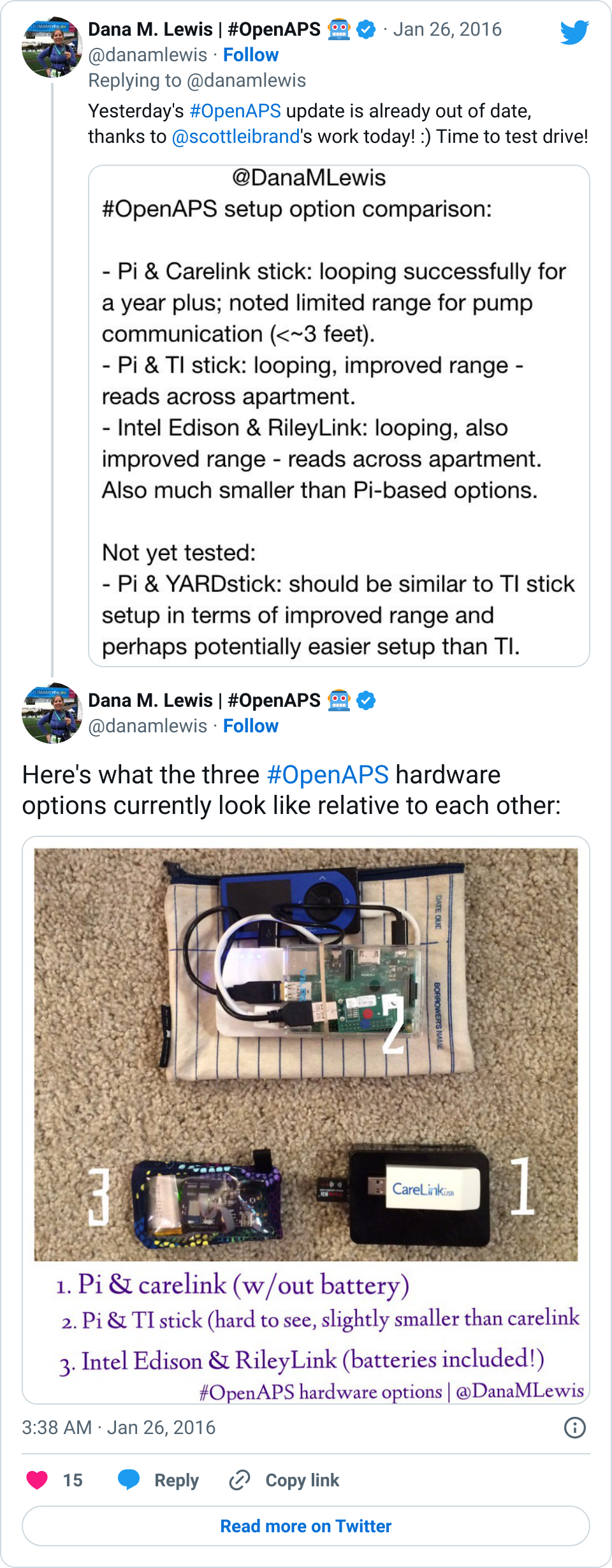

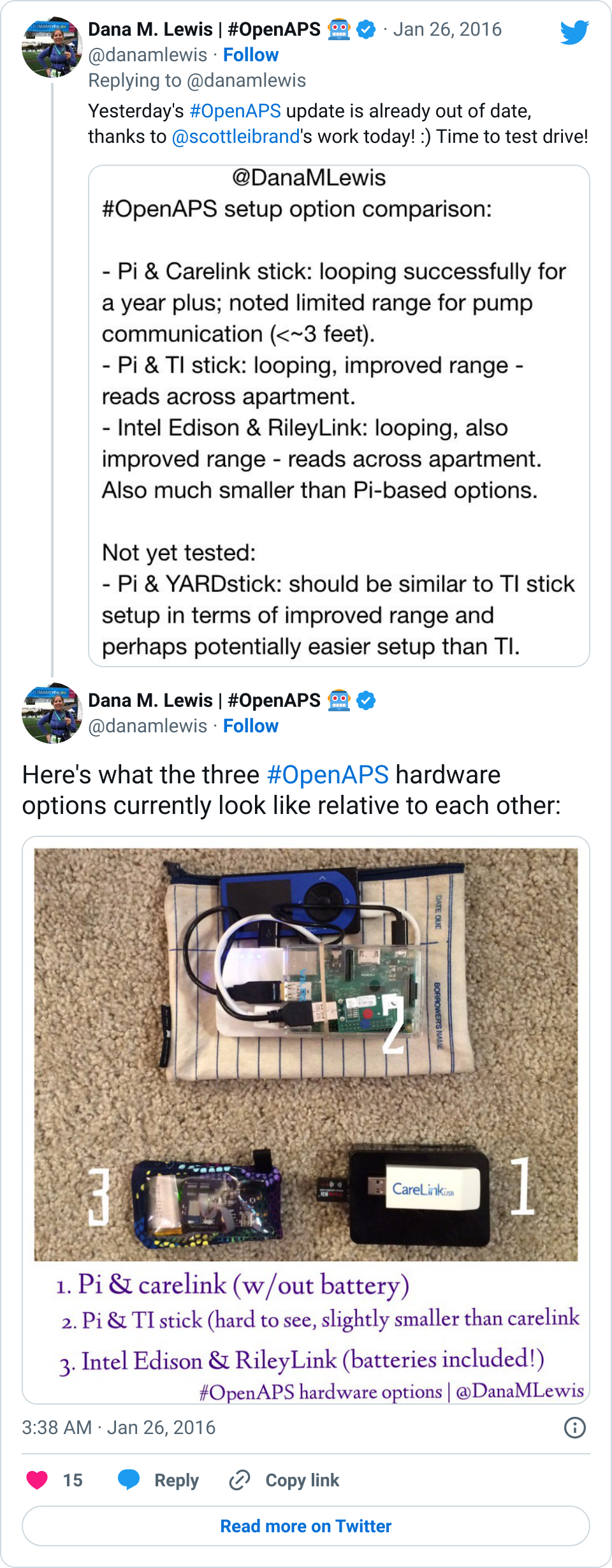

Some of the biggest improvements we’ve made to OpenAPS recently have been usability improvements. In February, someone kindly did the soldering of an Edison/Rileylink “rig” for me. This was just after I did a livestream Q&A with the TuDiabetes community, saying that I didn’t mind the size of my Raspberry Pi rig. I don’t. It works, it’s an artificial pancreas, the size doesn’t matter.

That being said… Wow! Having a small rig that clips to my pocket does wonders for being able to just run out the door and go to dinner, run an errand, go on an actual run, and more. I could do all those things before, but downsizing the rig makes it even easier, and it’s a fantastic addition to the already awesome experience of having a closed loop for the past 18 months (and >11,000 hours of looping). I’m so thankful for all of the people (Pete on Rileylink, Oscar on mmeowlink, Toby for soldering my first Edison rig for me, and many many others) who have been hard at work enabling more hardware options for OpenAPS, in addition to everyone who’s been contributing to algorithm improvements, assisting with improving the documentation, helping other people navigate the setup process, and more!

That leads me to today. I just finished participating in a month-long usability study focused on OpenAPS users. (One of the cool parts was that several OpenAPS users contributed heavily to the design of the study, too!) We tracked every day (for up to 30 days) any time we interacted with the loop/system, and it was fascinating.

At one point, for a stretch of 3 days, we counted how many times we looked at our BGs. Between my watch, 3 phone apps/ways to view my data, the CGM receivers, Scott’s watch, the iPad by the bed, etc: dozens and dozens of glances. I wasn’t too surprised at how many times I glance/notice my BGs or what the loop is doing, but I bet other people are. Even with a closed loop, I still have diabetes and it still requires me to pay attention to it. I don’t *have* to pay attention as often as I would without a closed loop, and the outcomes are significantly better, but it’s still important to note that the human is still ultimately in control and responsible for keeping an eye on their system.

That’s one of the things I’ve been thinking about lately: the need to set expectations when a loop comes out on the commercial market and is more widely available. A closed loop is a tool, but it’s not a cure. Managing type 1 diabetes will still require a lot of work, even with a polished commercial APS: you’ll still need to deal with BG checks, CGM calibrations, site changes, dealing with sites and sensors that fall out or get ripped out… And of course there will still be days where you’re sensitive or resistant and BGs are not perfect for whatever reason. In addition, it will take time to transition from the standard of care as we have it today (pump, CGM, but no algorithms and no connected devices) to open and/or closed loops.

This is one of the things among many that we are hoping to help the diabetes community with as a result of the many (80+ as of June 8, 2016!) users with #OpenAPS. We have learned a lot about trusting a closed loop system, about what it takes to transition, how to deal if the system you trust breaks, and how to use more data than you’re used to getting in order to improve diabetes care.

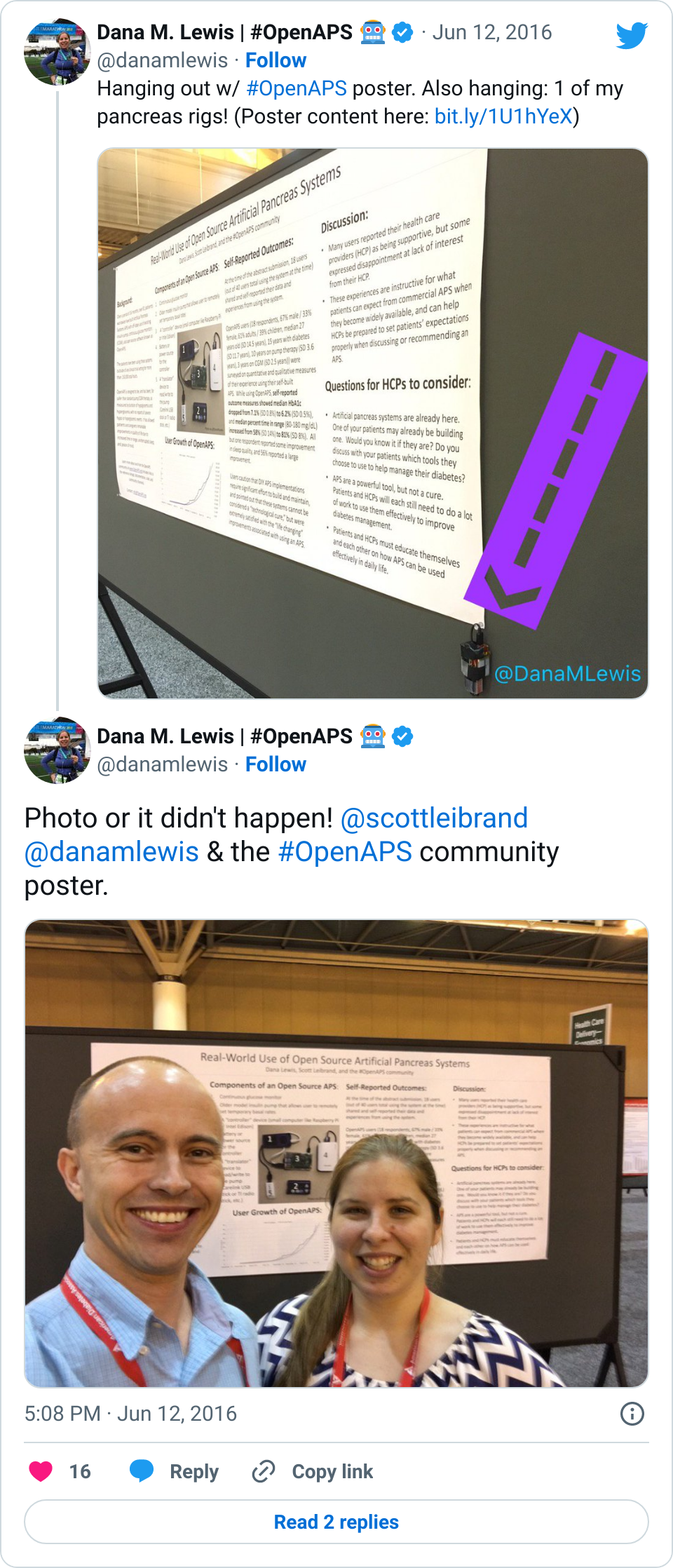

As a step to helping the healthcare provider community start thinking about some of these things, the #OpenAPS community submitted a poster that was accepted and will be presented this weekend at the 2016 American Diabetes Association Scientific Sessions meeting. This will be the first data published from the community, and it’s significant because it’s a study BY the community itself. We’re also working with other clinical research partners on various studies (in addition to the usability study, other studies to more thoroughly examine data from the community) for the future, but this study was a completely volunteer DIY effort, just like the entire OpenAPS movement has been.

Our hope is that clinicians walk away this weekend with insight into how engaged patients are and can be with their care, and a new way of having conversations with patients about the tools they are choosing to use and/or build. (And hopefully we’ll help many of them develop a deeper understanding of how artificial pancreas technology works: #OpenAPS is a great learning tool not only for patients, but also for all the physicians who have not had any patients on artificial pancreas systems yet.)

Stay tuned: the poster is embargoed until

Saturday morning, but we’ll be sharing our results online beginning this weekend once the embargo lifts! (The hashtag for the conference is #2016ADA, and we’ll of course be posting via

@OpenAPS and to

#OpenAPS with the data and any insights coming out of the conference.)

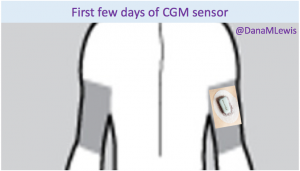

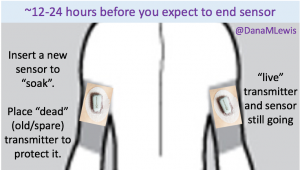

However, 12-24 hours before I expect my sensor to end, I insert my next sensor into my body. To protect the sensor (you don’t want the sensor filament itself to get torn off or lost in your body), I plop an old (“dead” battery) transmitter on it.

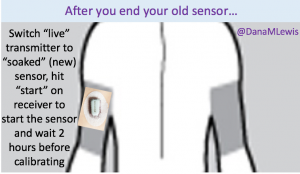

However, 12-24 hours before I expect my sensor to end, I insert my next sensor into my body. To protect the sensor (you don’t want the sensor filament itself to get torn off or lost in your body), I plop an old (“dead” battery) transmitter on it. The next day, when my sensor session ends:

The next day, when my sensor session ends: The outcome (for me) has always been significantly improved “first day” BG readings from the sensor. This works great when you can plan ahead and your outfits (don’t judge, sometimes you have important outfits like a wedding dress to plan around) and skin real estate support two sites on your body for 24 hours or so. This doesn’t work if you rip a sensor out by accident, so in those scenarios I go ahead and put a new sensor on, put the ‘live’ transmitter on, and hit ‘start’ to get through the 2 hour calibration period as soon as possible to get back to having live data. (All the while knowing that the first day is going to be more “meh” than it would be otherwise.)

The outcome (for me) has always been significantly improved “first day” BG readings from the sensor. This works great when you can plan ahead and your outfits (don’t judge, sometimes you have important outfits like a wedding dress to plan around) and skin real estate support two sites on your body for 24 hours or so. This doesn’t work if you rip a sensor out by accident, so in those scenarios I go ahead and put a new sensor on, put the ‘live’ transmitter on, and hit ‘start’ to get through the 2 hour calibration period as soon as possible to get back to having live data. (All the while knowing that the first day is going to be more “meh” than it would be otherwise.)

Recent Comments