#DIYPS (the Do-It-Yourself Pancreas System) was created by Dana Lewis and Scott Leibrand in the fall of 2013.

Curious about building a closed loop for yourself? Head to OpenAPS.org!

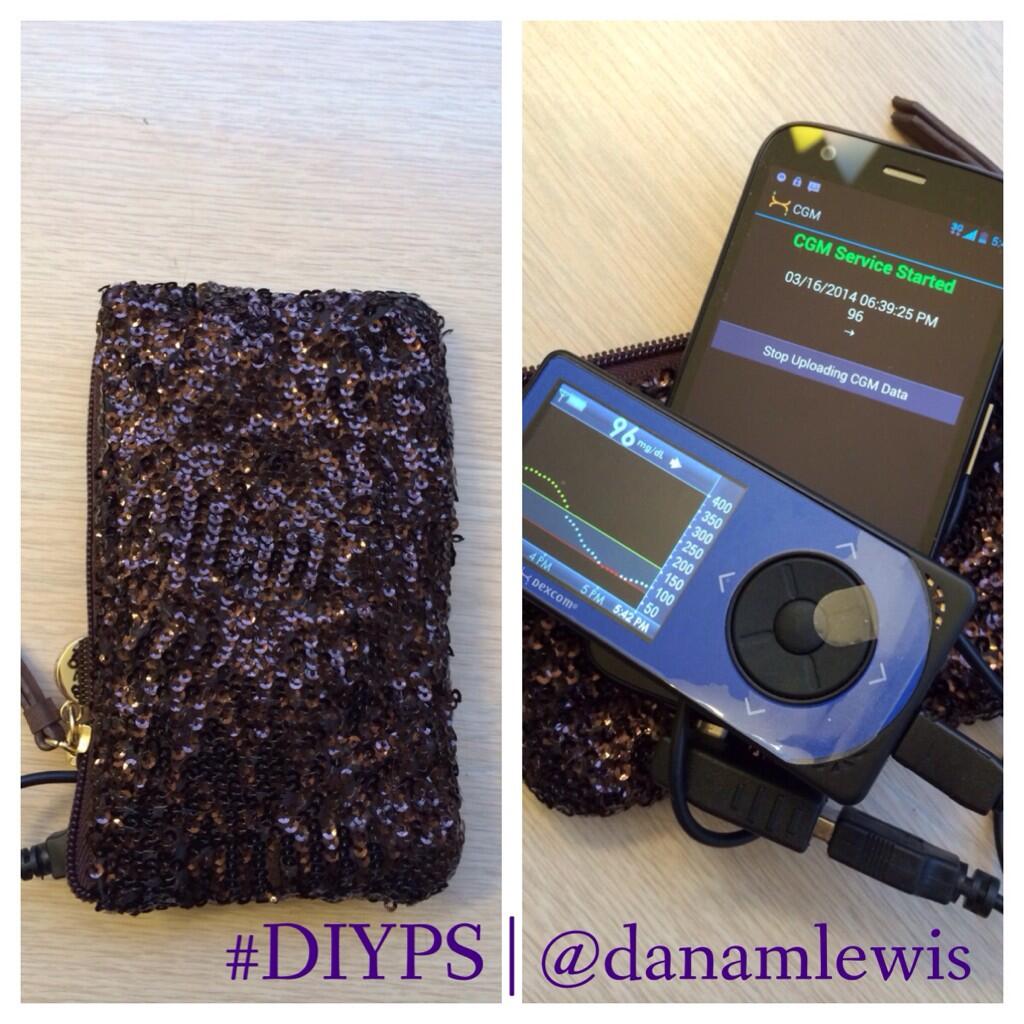

#DIYPS was originally developed with the goal of solving a well-known problem with an existing FDA-approved medical device. We originally set out to figure out a way to augment continuous glucose monitor (CGM) alerts, which aren’t loud enough to wake heavy sleepers, and to alert a loved one if the patient is not responding.

We were able to solve those problems and include additional features such as:

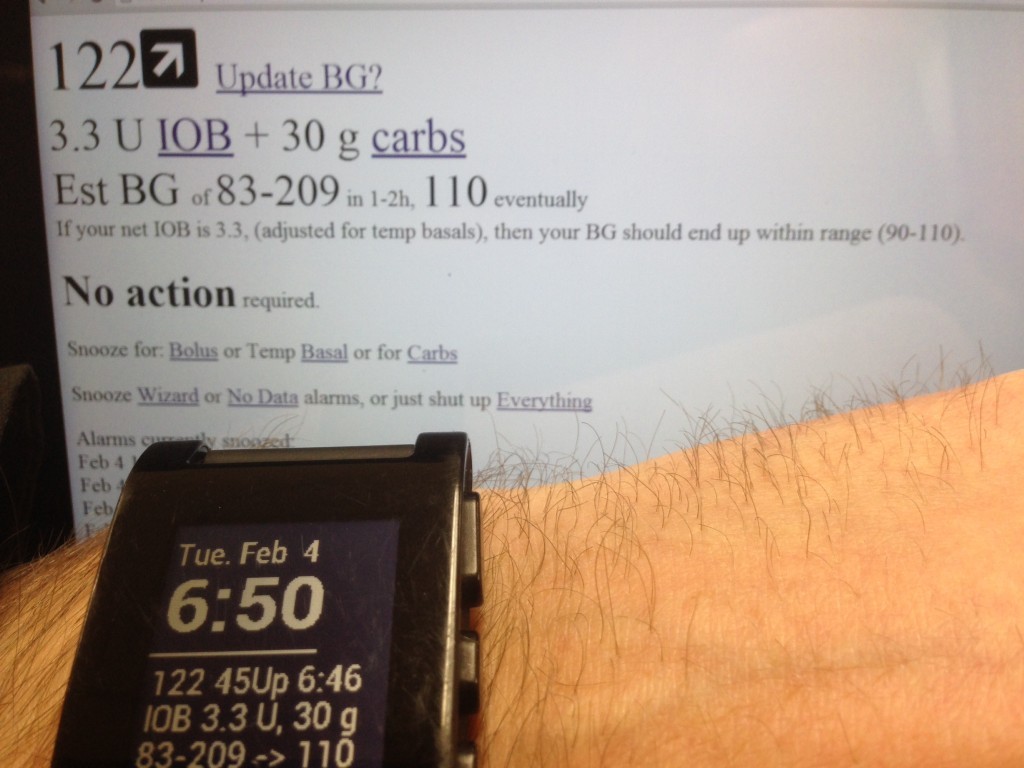

- Real-time processing of blood glucose (BG), insulin on board, and carbohydrate decay

- Customizable alerts based on CGM data and trends

- Real-time predictive alerts for future high or low BG states (hours in advance)

- Continually updated recommendations for required insulin or carbs

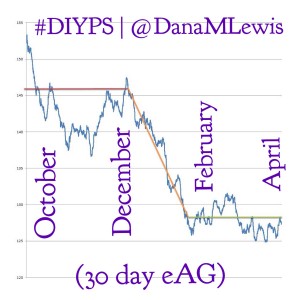

- ..and as of December 2014, we ‘closed the loop’ and have #DIYPS running as a closed loop artificial pancreas.

- (And, as of February 2015, we also launched #OpenAPS, an open and transparent effort to make safe and effective basic Artificial Pancreas System (APS) technology widely available. For more details, check out OpenAPS.org)

You can read this post for more details about how the #DIYPS system works.

While #DIYPS was invented for purposes of better using a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) and initially tailored for use with an insulin pump, what we discovered is that the concepts behind #DIYPS can actually be used with many types of diabetes technology. It can be utilized by those with:

- CGM and insulin pump

- CGM and multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin

- no CGM (fingerstick testing with BG meter) and insulin pump

- no CGM (fingerstick testing with BG meter) and multiple daily injections (MDI) of insulin

Here are some frequently asked questions about #DIYPS:

- Q: “I love it. How can I get it?“A: #DIYPS is n=1, and because it is making recommendations based on CGM data, we previously have said that we can not publicly post the code to enable someone else to utilize #DIYPS as-is. There’s two things to know. 1) To get some of the same benefits from #DIYPS as an “open loop” system, with alerts and BG visualizations, you can get Nightscout, which includes all of the publicly-available components of #DIYPS, including the ability to upload Dexcom CGM data, view it on any web browser and on a Pebble watch, and get basic alarms for high and low BG – and depending on which features you enable, you can also get predictive alarms. Some of the other core #DIYPS features (“eating-soon mode“, and sensitivity/resistance/activity modes) are now available in Nightscout. 2) If you are interested in your own closed loop system, check out OpenAPS.org and review the available OpenAPS documentation on Github to help you determine if you have the necessary equipment and help you determine whether you want to do the work to build your own implementation.

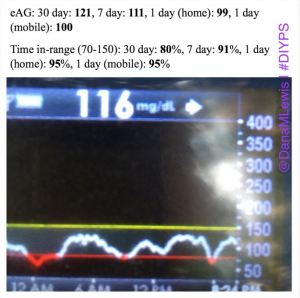

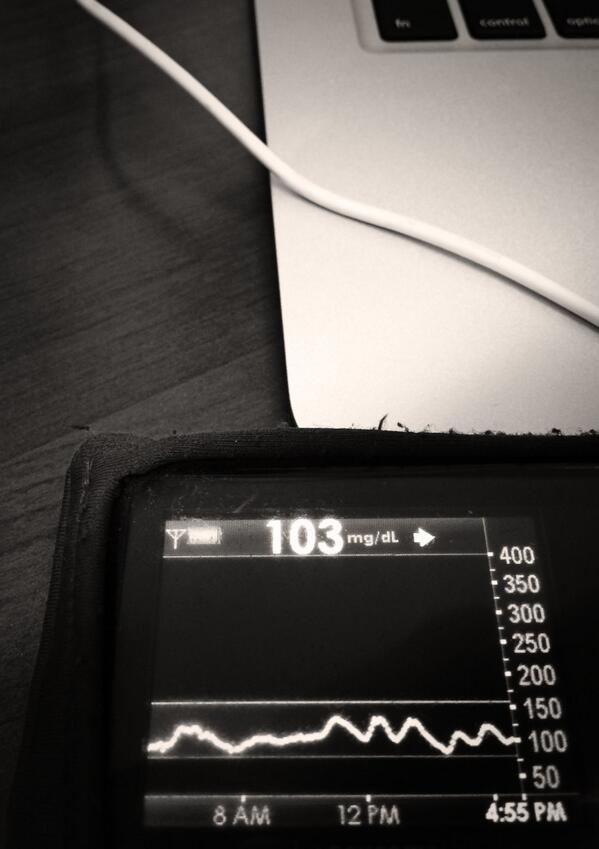

- Q: “Does #DIYPS really work?”A: Yes! For N=1, using the “open loop” style system with predictive alerts and notifications, we’ve seen some great results. Click here to read a post about the results from #DIYPS after the first 100 days – it’s comparable to the bionic pancreas trial results. Or, click here to read our results after using #DIYPS for a full year. We should probably update this to talk about the second year of using #DIYPS, but the results from the first year have been sustained (yay!) and also augmented by the fact that we closed the loop and have the system auto-adjusting basal rates while I sleep.

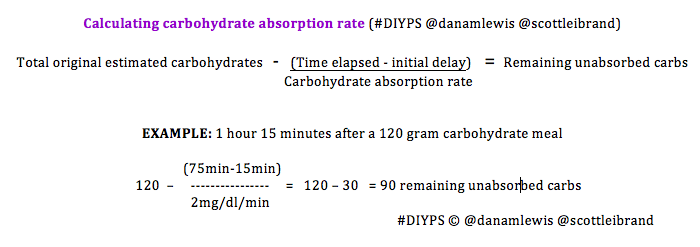

- Q: “Why do you think #DIYPS works?”A: There could be some correlation with increased timed/energy spent thinking about diabetes compared to normal. (We’d love to do some small scale trials comparing people who use CGMs with easy access to time-in-range metrics and/or eAG data, to compare this effect). And, #DIYPS has also taught us some key lessons related to pre-bolusing for meals and the importance of having insulin activity in the body before a meal begins. You should read 1) this post that talks about our lessons learned from #DIYPS; 2) this post that gives a great example of how someone can eat 120 grams of carbohydrates of gluten-free pizza with minimal impact to blood glucose levels with the help of #DIYPS; 3) this post that will enable you to find out your own carbohydrate absorption rate that you can start using to help you decide when and how you bolus/inject insulin to handle large meals or 4) this post talking about how you can manually enact “eating-soon mode”. And of course, the key reason #DIYPS works (in open loop mode) is because it reduces the cognitive load for a person with diabetes by constantly providing push notifications and real time alerts and predictions about what actions a person with diabetes might need to consider taking. (Read more detail from this post about the background of the system.)

- Q: “Awesome! What’s next?“A: If you haven’t read about #OpenAPS, we encourage you to check it out at OpenAPS.org. This is where we have taken the inspiration and lessons learned from using #DIYPS in manual mode (i.e. before we closed the loop), and from our first version of a closed loop and are paying it forward with a community of collaborators to make it possible for other people to close the loop! Some new features we wanted for #DIYPS that will likely still happen, but integrated with Nightscout and/or #OpenAPS include:

- calculation of insulin activity and carb absorption curves (and from there, ISF & IC ratios, etc.) from historical data

- better-calibrated BG predictions using those calculated absorption curves (with appropriate error bars representing predictive uncertainty)

- recommendations for when to change basal rates, based on observed vs. predicted BG outcomes

- integration with activity tracking and calendar data

- closing the loop – done as of December 2014!

and made possible for more than (n=1) with #OpenAPS as of February 2015

and made possible for more than (n=1) with #OpenAPS as of February 2015

We also are collaborating with medical technology and device companies, the FDA, and other projects and organizations like Tidepool, to make sure that the ideas, insights, and features inspired by our original work on #DIYPS get integrated as widely as possible. Stay tuned (follow the #DIYPS hashtag, Dana Lewis & Scott Leibrand on Twitter, and keep an eye on this blog) for more details about what we’re up to.

- Q: “I love it. What can I do to help the #DIYPS project? (or #openAPS)”A: #DIYPS is still a Dana-specific thing, but #OpenAPS is open source and a great place to contribute. First and foremost, if you have any ability to code (or a desire to learn), we need contributors to both the Nightscout project as well as #OpenAPS. There are many things to work on, so we need as many volunteers, with as many different types of skills, as we can get. For those who are less technical, the CGM in the Cloud Facebook group is a great place to start. For those who are technical and/or want to close the loop for themselves, check out OpenAPS.org, join the openaps-dev google group, and hop on the #intend-to-bolus channel on Gitter. If you want to contact us directly, you can reach out to us on Twitter (@DanaMLewis @ScottLeibrand) or email us (dana@openAPS.org and scott@openAPS.org). We’d also love to know if you’re working on a similar project or if you’ve heard of something else that you think we should look into for a potential #OpenAPS feature or collaboration.

Recent Comments