I have to ask myself these days, is this a software-shaped feeling?

This is a riff on something I see online more and more frequently, where people comment about recognizing if this is a “software-shaped problem”. Meaning, is this something that can be solved with software? More recently, this often means n=1 custom, boutique software that we can build ourselves. This is often easier and even faster than trying to search for something that maybe exists elsewhere and kinda works but not perfectly and requires a lot of work to tweak to the use case. Instead, now, we can spend the same (or often a lot less) time building something that perfectly fits.

I have been doing this for years. Juggling data in my head is hard – so I often turn to spreadsheets. For example, trying to figure out my enzyme dosing originally for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency – I had too many meals and too many variables to track, so I made a spreadsheet. When I then incorporated dosing enzymes for everything that I ate, that meant also everything I was eating while ultrarunning – which I did every 30 minutes to fuel. So I made a spreadsheet for that and then a template with dropdowns to use while running. I could quickly enter data that way, but Google sheets was slow to load on my phone and the extra seconds of delay was frustrating. Thus, I made a simple app I called “Macros On The Run” to allow me to more quickly open and tap the drop down and select my fuel item. Since I was building a custom app interface I could have all the summary data I wanted from my run, both hourly stats on calories and sodium consumed but also the entire per-run stats. I then was able to export my data to be able to analyze it later (particularly, also transposing it into the spreadsheet I use for food and enzyme intake). Does anyone else have this use case? No, probably not. But it was so empowering to be able to track and capture information in a format that worked well for me. And because I had learned how to build apps to build PERT Pilot to share with other people (because not everyone loves spreadsheet interfaces), I knew how to build apps, so I had the skillset that translated to figuring out how to build another app. This was before agentic AI, by the way, but this is now even easier.

Enter this week. I realized that I had expressed frustration to both my mom and Scott about a situation where I have a medicine/treatment that is done once a week, but it’s not a time-anchored or time-specific treatment. I don’t always take it Tuesday at 7pm. Depending on my schedule it could be 5pm, 9pm, whatever. But also, if I’m traveling, it can be a day earlier or later. It’s 7 days, plus or minus one day. Previously I was adding an event to the calendar for every week, and then moving it around. But I realized looking ahead at a busy summer full of travel that it was hard to move one without having to move another, because it’s not the week before that only matters, moving one also influences the chain of following events. If I usually do it on Tuesday but I’ll be traveling and not home until Thursday (and don’t want to do it while traveling), then I need to move the previous week from Tuesday to Wednesday so the following week’s Thursday is not out of the allowed ‘window’. So instead of 7-7-7, or ending up with 7-9-5 (which means two weeks are out of bounds), it becomes 7-8-6. But because these are single calendar events, there’s no alert when something goes out of bounds/out of the ‘allowed window’. Setting a recurring event (eg calendar event every 7 days) doesn’t resolve this, either. Juggling all of this in my head felt like a waste and non-optimal.

If only, I thought, I had a way to create an event type that was based on the “chain” relationship to the events before and after, that I could set to every 7 days but have an ‘allowed’ grace window of plus or minus a day, so that anything 6-8 days was allowed.

Google calendar doesn’t support this. But I know that you can subscribe to other calendars and show them, eg how I edit events in TripIt and subscribe to the calendar feed so I can see those events in Google calendar.

Thus, I found myself asking, “is this a software-shaped feeling?” of frustration? I can build apps, after all. Could I build an app that somehow publishes a calendar feed that I can see in Google calendar and see these events and get alerts when they are out of bounds? Ideally I’d be able to use Google calendar to edit these events, the way I do my other calendar events.

The mental model I had was app>feed>display in calendar. I was laying in bed, but I pulled open one of my LLMs that I have on my phone and sketched out the idea in a few sentences and asked what was possible to do and what technically it would take to do this. It brainstormed two key options, one with Google authentication and complicated multi-step back end (storage and databases and hosting and servers and all the stuff I *can* do but hate doing and doesn’t make sense for a quick n=1 prototype), and one simple one where the app would create its own iCloud calendar and then publish a feed I could see via the Google calendar. Aha, I thought, that’s it.

The next day I sat down at my laptop and used my coding LLM of choice. I asked it to build this app where it would allow me to create a ‘series’ of events with a set window (eg default to Tuesday at 7pm) and allow me to set a grace period (eg +/-1 day) and see the distance between events and flag a visual cue if they fall out of the window. It should then create events in an iCloud calendar. I would then subscribe and view it via Google calendar, so I could see it via my laptop or phone. Eventually I would see if I could edit it from those views, but for now, just being able to push and adjust from the app would be fine. (Note: my prompt was a little more specific than this, but the important part wasn’t telling it how to build the app or what I wanted it to look like. The important part is making sure it understands the end goal and user interactions so we design the backend and the front end to support what I actually want to do as the end user.)

It…did it. This isn’t a story of “one-shotting” and getting things perfectly from a single prompt, but I continue to be appreciative that the first hours of setting up a project and getting it to build on your device and get the basic functionality working that used to take 4-6 hours and lots of gnashing teeth is now a 15-20 minute endeavor, usually. And that’s what happened here, I had a working functional prototype working on my phone in about 15 minutes. I spent more time after that making it look better, testing it, adjusting events, etc, but the initial setup and functionality was a very quick process. That’s huge. For me, it doesn’t matter what the total amount of time it is to get a project ‘done’ or usable for real-life testing. You’ll see people talk about how you get 80% of the work done quicker but it ‘takes longer’ for the last 20%, but I honestly think I do way more (so it’s not just 20%) when I haven’t exhausted myself gnashing my teeth about the fundamental basic how-does-it-work and does-it-build and what-is-this-build-error.

This app probably doesn’t matter to anyone else, but if you have a use case for it and would like to try it, let me know. I called it SchedulerPilot. It creates a new iCloud calendar called SchedulerPilot that you can see on your phone, and then also subscribe to elsewhere to view (e.g. if you set it to be viewable via a link), such as in Google calendar. That means I can give Scott access to see it the way he sees my other calendars, plus view it from my browser-based calendar view on my laptop. I can’t edit events from Google calendar in the browser, but I was able to (much more easily than I expected) add functionality to edit directly from my phone’s calendar app the way I usually do on the go. I also then was able to add functionality in the app for it to flag when the in-app view and calendar view were out of sync. It shows a list of events and how they differ and I can choose whether I pull calendar changes into the app view, or if I did the tweaking in the app, push those changes back to the calendar. They automatically sync. I can also add notes to the event and ‘lock’ it so if I make other adjustments and push updates, it doesn’t overwrite it. This is key for travel-based constraints where I am definitively moving it to do when I get home from a trip, but sometimes I haven’t booked flights for the trip so looking at my calendar it may otherwise be confusing WHY the event is moved for the week. Having a lock shows it’s there for a reason, and the optional note also provides good context clue for why it’s moved. I can also add more events in the future with the tap of a button, if I’m still using this as my method for scheduling in the future (and I’m guessing I will be).

Here’s an animated demo showing the point of the app and why it’s useful:

The point isn’t convincing you to want to use my app. Most people don’t have a use case for this. But I want more people to build the patterns of recognizing when their feelings are trying to tell them something (e.g. this is a problem we could work on improving, even if it is not solvable) and build the skills of identifying when this is a software-shaped feeling. Especially when we are dealing with health-related situations and especially chronic non-curable diseases, and especially ones with treatments or medications that are not fun, it is so important to solve friction and frustration whenever and wherever we can. Not everything is a software-shaped feeling, but the more we recognize and address, the better off we are. Or at least I am, and I hope to help others do the same.

The point isn’t convincing you to want to use my app. Most people don’t have a use case for this. But I want more people to build the patterns of recognizing when their feelings are trying to tell them something (e.g. this is a problem we could work on improving, even if it is not solvable) and build the skills of identifying when this is a software-shaped feeling. Especially when we are dealing with health-related situations and especially chronic non-curable diseases, and especially ones with treatments or medications that are not fun, it is so important to solve friction and frustration whenever and wherever we can. Not everything is a software-shaped feeling, but the more we recognize and address, the better off we are. Or at least I am, and I hope to help others do the same.

PS – If you find yourself with a software-shaped feeling and aren’t sure where to start, feel free to reach out and I’m happy to help chat and brainstorm and help you figure out which LLM tools work for you to help build software that fit those feelings. (Even if you tried a particular LLM in the past, they are frequently updating models and tools and it is worth trying again. They have gotten way better and require way less specific prompting, like I outlined here – although there may be some tips you still find useful in this post.) It used to be that you had to fund someone or badger someone to help build something if you didn’t have previous technical skills (or invest a LOT of time and energy) to learn them to do a thing. Now, you don’t have to do that, or plan to have a company to get funding to build a prototype. You can just…build things. And it’s ok if it’s “just” a n=1 solution. If it works for you, it’s worth the time. And chances are, it’ll be something that works for someone else, too. And in the meantime, you’ll have made something that works for you. If you felt like you needed permission, you have it. It won’t fix everything, but that doesn’t mean you should fixing what you can. It feels really good to have forward progress and to do something productive.

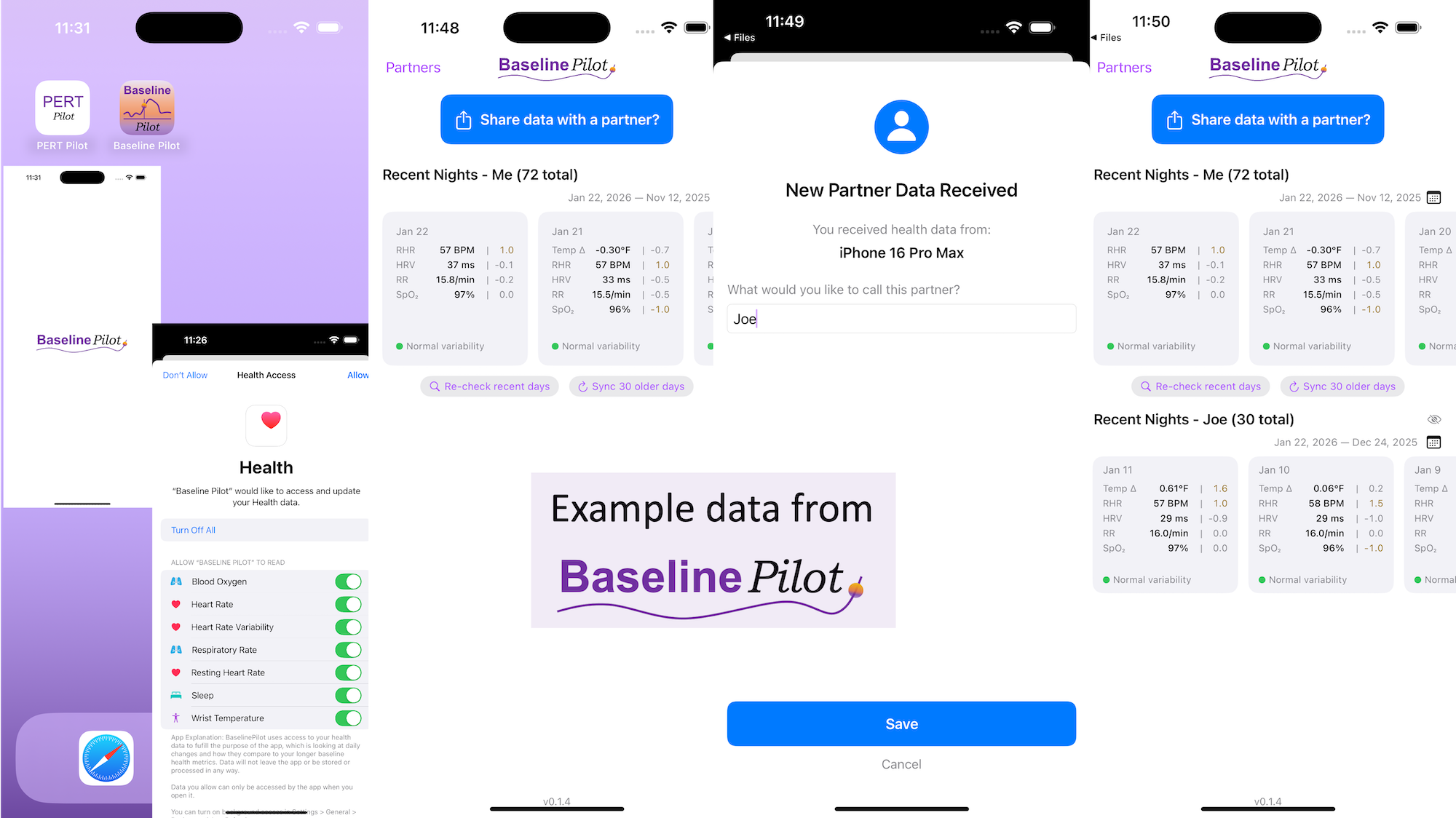

All of this data is local to the app and not being shared via a server or anywhere else. It makes it quick and easy to see this data and easier to spot changes from your normal, for whatever normal is for you. It makes it easy to share with a designated person who you might be interacting with regularly in person or living with, to make it easier to facilitate interventions as needed with major deviations. In general, I am a big fan of being able to see my data and the deviations from baseline for all kinds of reasons. It helps me understand my recovery status from big endurance activities and see when I’ve returned to baseline from that, too. Plus the spotting of infections earlier and preventing spread, so fewer people get sick during infection season. There’s all kinds of reasons someone might use this, either to quickly see their own data (the Vitals access problem) or being able to share it with someone else, and I love how it’s becoming easier and easier to whip up custom software to solve these data access or display ‘problems’ rather than just stewing about how the standard design is blocking us from solving these issues!

All of this data is local to the app and not being shared via a server or anywhere else. It makes it quick and easy to see this data and easier to spot changes from your normal, for whatever normal is for you. It makes it easy to share with a designated person who you might be interacting with regularly in person or living with, to make it easier to facilitate interventions as needed with major deviations. In general, I am a big fan of being able to see my data and the deviations from baseline for all kinds of reasons. It helps me understand my recovery status from big endurance activities and see when I’ve returned to baseline from that, too. Plus the spotting of infections earlier and preventing spread, so fewer people get sick during infection season. There’s all kinds of reasons someone might use this, either to quickly see their own data (the Vitals access problem) or being able to share it with someone else, and I love how it’s becoming easier and easier to whip up custom software to solve these data access or display ‘problems’ rather than just stewing about how the standard design is blocking us from solving these issues!

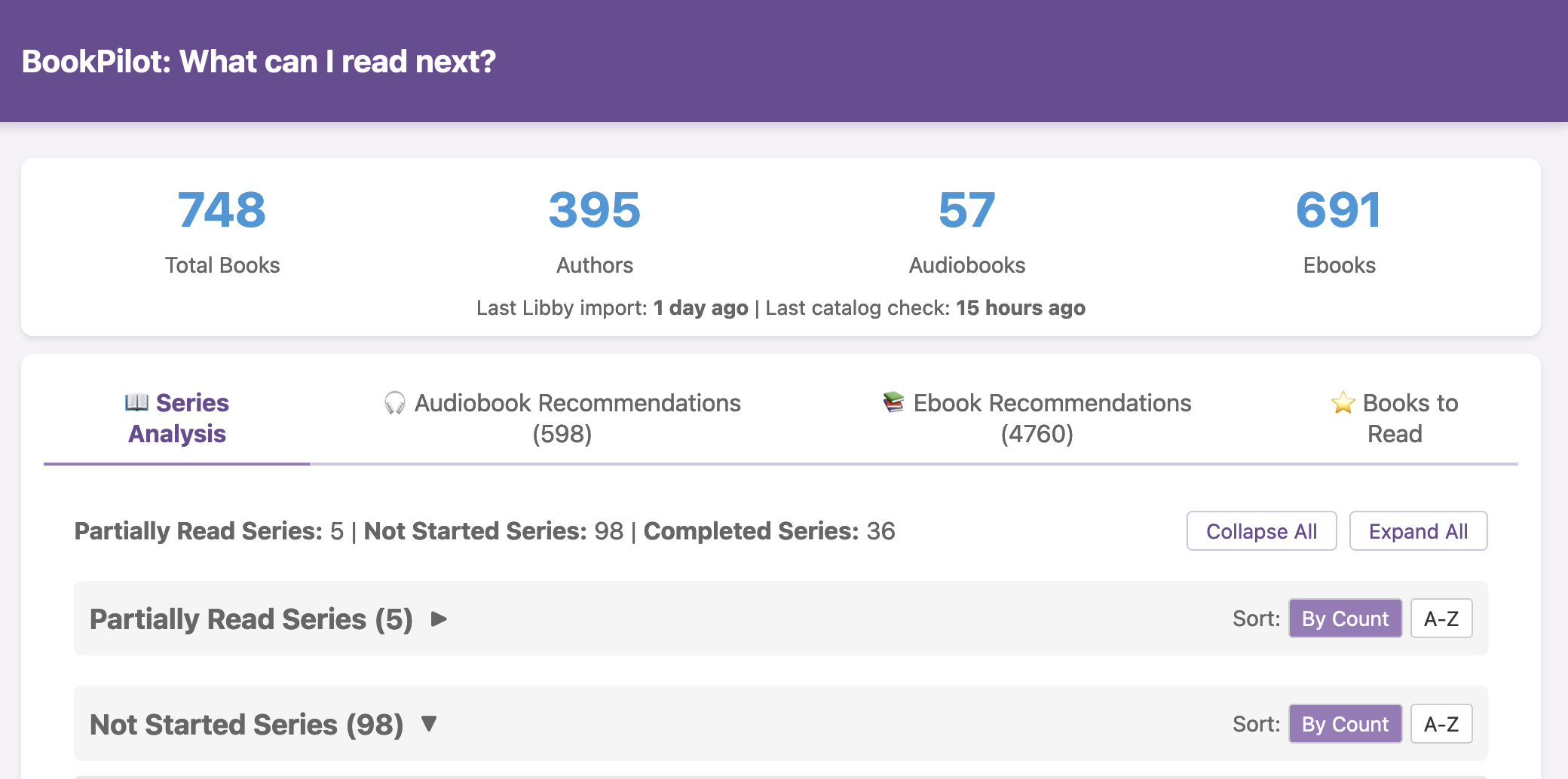

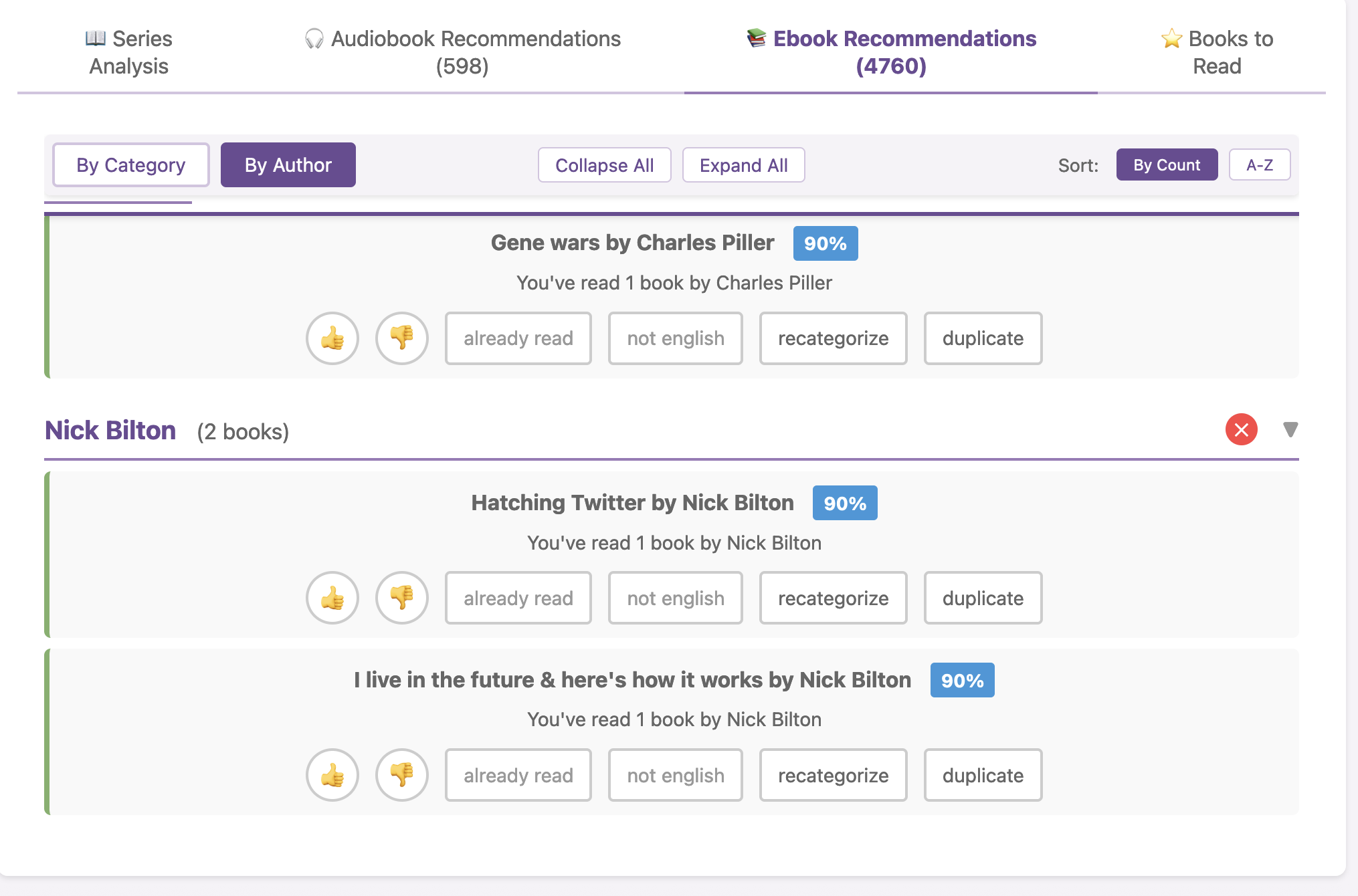

I haven’t open-sourced BookPilot yet, but I can – if this sounds like something you’d like to use, let me know and I can put it on Github for others to use. (You’d be able to download it and run it on the command line and/or in your browser like a website, and drop your export of Libby data into the folder for it to use). (And did I use AI to help build this? Yes. Could you one-shot a duplicate of this yourself? Maybe, or otherwise yes you could in several hours replicate this on your own. In fact, it would be a great project to try yourself – then you could design the interface YOU prefer and make it look exactly how you want and optimize for the features you care about!) Update: I have heard from several folks already that they might be interested, so I have on my list to tidy this up a bit and push it to Github! If you want me to ping you once it goes up, drop a comment below or email me or ping me on Twitter or BlueSky.

I haven’t open-sourced BookPilot yet, but I can – if this sounds like something you’d like to use, let me know and I can put it on Github for others to use. (You’d be able to download it and run it on the command line and/or in your browser like a website, and drop your export of Libby data into the folder for it to use). (And did I use AI to help build this? Yes. Could you one-shot a duplicate of this yourself? Maybe, or otherwise yes you could in several hours replicate this on your own. In fact, it would be a great project to try yourself – then you could design the interface YOU prefer and make it look exactly how you want and optimize for the features you care about!) Update: I have heard from several folks already that they might be interested, so I have on my list to tidy this up a bit and push it to Github! If you want me to ping you once it goes up, drop a comment below or email me or ping me on Twitter or BlueSky.  I know some of the answers to the question of why clinicians aren’t doing this. But, the question I asked the Stanford AI+Health audience was to consider why we focus so much on informed consent for taking action, but we ignore the risks and negative outcomes that occur when not taking action.

I know some of the answers to the question of why clinicians aren’t doing this. But, the question I asked the Stanford AI+Health audience was to consider why we focus so much on informed consent for taking action, but we ignore the risks and negative outcomes that occur when not taking action. AI often gives us new capabilities to do these things, even if it’s different from the way someone might do it manually or without the disability. And for us, it’s often not a choice of “do it manually or do it differently” but a choice of “do, with AI, or don’t do at all because it’s not possible”. Accessibility can be about creating equitable opportunities, and it can also be about preserving energy, reducing pain, enhancing dignity, and improving quality of life in the face of living with a disability (or multiple disabilities). AI can amplify our existing capabilities and super powers, but it can also level the playing field and allow us to do more than we could before, more easily, with fewer barriers.

AI often gives us new capabilities to do these things, even if it’s different from the way someone might do it manually or without the disability. And for us, it’s often not a choice of “do it manually or do it differently” but a choice of “do, with AI, or don’t do at all because it’s not possible”. Accessibility can be about creating equitable opportunities, and it can also be about preserving energy, reducing pain, enhancing dignity, and improving quality of life in the face of living with a disability (or multiple disabilities). AI can amplify our existing capabilities and super powers, but it can also level the playing field and allow us to do more than we could before, more easily, with fewer barriers. These are actionable, doable, practical things we can all be doing, today, and not just gnashing our teeth. The sooner we course correct with improved data availability, the better off we’ll all be in the future, whether that’s tomorrow with better clinical care or in years with AI-facilitated diagnoses, treatments, and cures.

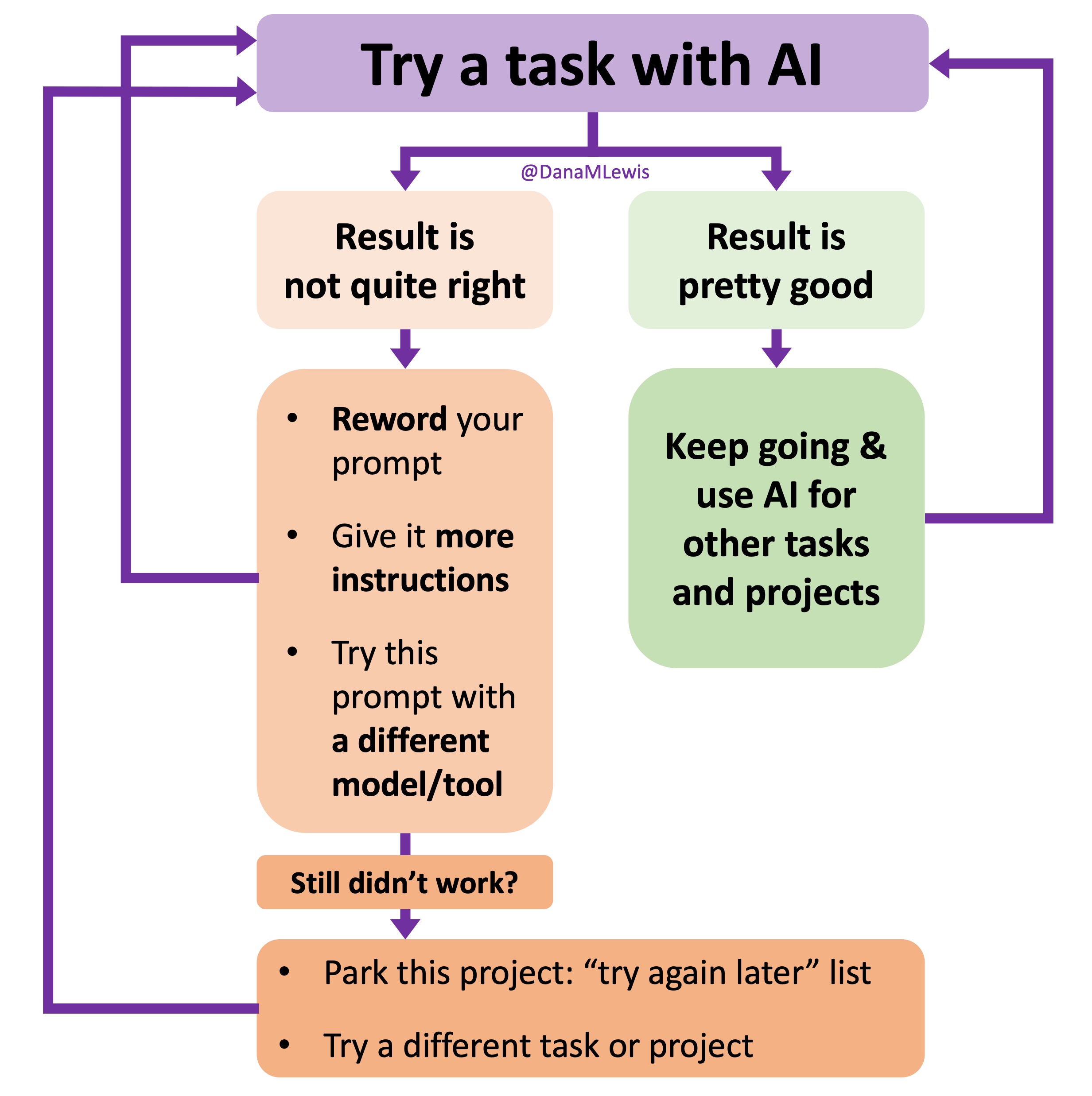

These are actionable, doable, practical things we can all be doing, today, and not just gnashing our teeth. The sooner we course correct with improved data availability, the better off we’ll all be in the future, whether that’s tomorrow with better clinical care or in years with AI-facilitated diagnoses, treatments, and cures.  I’ve started making a list of projects or tasks I want to work on where the AI isn’t quite there yet and/or I haven’t figured out a good setup, the right tool, etc. A good example of this was

I’ve started making a list of projects or tasks I want to work on where the AI isn’t quite there yet and/or I haven’t figured out a good setup, the right tool, etc. A good example of this was  TL;DR: as more and more people are going to vibe code their way to having Android and/or iOS apps, it’s very feasible for people with less experience to do both and to distribute apps on both platforms (iOS App Store and Google Play Store for Android). However, there’s an up front higher cost to iOS ($99/year) but a slightly easier, more intuitive experience for deploying your apps and getting them reviewed and approved. Conversely, Android development, despite its lower entry cost ($25 once), involves navigating a more complicated development environment, less intuitive deployment processes, and opaque requirements for app approval. You pay with your time, but if you plan to eventually build multiple apps, once you figure it out you can repeat the process more easily. Both are viable paths for app distribution if you’re building iOS and Android apps in the LLM-era of assisted coding, but don’t be surprised if you hit bumps in the road for deploying for testing or production.

TL;DR: as more and more people are going to vibe code their way to having Android and/or iOS apps, it’s very feasible for people with less experience to do both and to distribute apps on both platforms (iOS App Store and Google Play Store for Android). However, there’s an up front higher cost to iOS ($99/year) but a slightly easier, more intuitive experience for deploying your apps and getting them reviewed and approved. Conversely, Android development, despite its lower entry cost ($25 once), involves navigating a more complicated development environment, less intuitive deployment processes, and opaque requirements for app approval. You pay with your time, but if you plan to eventually build multiple apps, once you figure it out you can repeat the process more easily. Both are viable paths for app distribution if you’re building iOS and Android apps in the LLM-era of assisted coding, but don’t be surprised if you hit bumps in the road for deploying for testing or production. I’ve learned from experience that waiting rarely creates better outcomes. It only delays impact.

I’ve learned from experience that waiting rarely creates better outcomes. It only delays impact. I encourage you to think about scaling yourself and identifying a task or series of tasks where you can get in the habit of leveraging these tools to do so. Like most things, the first time or two might take a little more time. But once you figure out what tasks or projects are suited for this, the time savings escalate. Just like learning how to use any new software, tool, or approach. A little bit of invested time up front will likely save you a lot of time in the future.

I encourage you to think about scaling yourself and identifying a task or series of tasks where you can get in the habit of leveraging these tools to do so. Like most things, the first time or two might take a little more time. But once you figure out what tasks or projects are suited for this, the time savings escalate. Just like learning how to use any new software, tool, or approach. A little bit of invested time up front will likely save you a lot of time in the future.

Recent Comments