I think differently from most people. Sometimes, this is a strength; and sometimes this is a challenge. This is noticeable when I approach healthcare encounters in particular: the way I perceive signals from my body is different from a typical person. I didn’t know this for the longest time, but it’s something I have been becoming more aware of over the years.

The most noticeable incident that brought me to this realization involved when I pitched head first off a mountain trail in New Zealand over five years ago. I remember yelling – in flight – help, I broke my ankle, help. When I had arrested my fall, clung on, and then the human daisy chain was pulling me back up onto the trail, I yelped and stopped because I could not use my right ankle to help me climb up the trail. I had to reposition my knee to help move me up. When we got up to the trail and had me sitting on a rock, resting, I felt a wave of nausea crest over me. People suggested that it was dehydration and I should drink. I didn’t feel dehydrated, but ok. Then because I was able to gently rest my foot on the ground at a normal perpendicular angle, the trail guides hypothesized that it was not broken, just sprained. It wasn’t swollen enough to look like a fracture, either. I felt like it hurt really bad, worse than I’d ever hurt an ankle before and it didn’t feel like a sprain, but I had never broken a bone before so maybe it was the trauma of the incident contributing to how I was feeling. We taped it and I tried walking. Nope. Too-strong pain. We made a new goal of having me use poles as crutches to get me to a nearby stream a half mile a way, to try to ice my ankle. Nope, could not use poles as crutches, even partial weight bearing was undoable. I ended up doing a mix of hopping, holding on to Scott and one of the guides. That got exhausting on my other leg pretty quickly, so I also got down on all fours (with my right knee on the ground but lifting my foot and ankle in the air behind me) to crawl some. Eventually, we realized I wasn’t going to be able to make it to the stream and the trail guides decided to call for a helicopter evacuation. The medics, too, when they arrived via helicopter thought it likely wasn’t broken. I got flown to an ER and taken to X-Ray. When the technician came out, I asked her if she saw anything obvious and whether it looked broken or not. She laughed and said oh yes, there’s a break. When the ER doc came in to talk to me he said “you must have a really high pain tolerance” and I said “oh really? So it’s definitely broken?” and he looked at me like I was crazy, saying “it’s broken in 3 different places”. (And then he gave me extra pain meds before setting my ankle and putting the cast on to compensate for the fact that I have high pain tolerance and/or don’t communicate pain levels in quite the typical way.)

A week later, when I was trying not to fall on my broken ankle and broke my toe, I knew instantly that I had broken my toe, both by the pain and the nausea that followed. Years later when I smashed another toe on another chair, I again knew that my toe was broken because of the pain + following wave of nausea. Nausea, for me, is apparently a response to very high level pain. And this is something I’ve carried forward to help me identify and communicate when my pain levels are significant, because otherwise my pain tolerance is such that I don’t feel like I’m taken seriously because my pain scale is so different from other people’s pain scales.

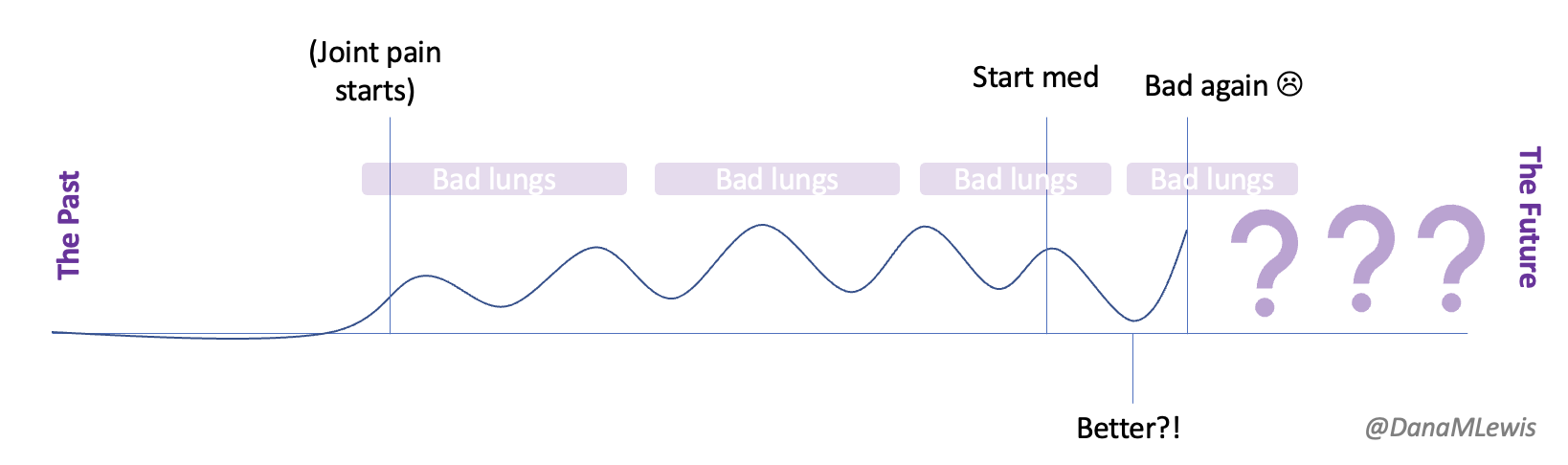

Flash forward to the last few weeks. I have an autoimmune disease causing issues with multiple areas of my body. I have some progressive slight muscle weakness that began to concern me, especially as it spread to multiple limbs and areas of my body. This was followed with pain in different parts of my spine which has escalated. Last weekend, riding in the car, I started to get nauseous from the pain and had to take anti-nausea medicine (which thankfully helped) as well as pain medicine (OTC, and thankfully it also helped lower it down to manageable levels). This has happened several other times.

Some of the symptoms are concerning to my healthcare provider and she agreed I should probably have a MRI and a consult from neurology. Sadly, the first available new patient appointment with the neurologist I was assigned to was in late September. Gulp. I was admittedly nervous about my symptom progression, my pain levels (intermittent as they are), and how bad things might get if we are not able to take any action between now and September. I also, admittedly, was not quite sure how I would cope with the level of pain I have been experiencing at those peak moments that cause nausea.

I had last spoken to my provider a week prior, before the spine pain started. I reached out to give her an update, confirm that my specialist appointment was not until September, and express my concern about the progression and timeline. She too was concerned and I ended up going in for imaging sooner.

Over the last week, because I’ve been having these progressive symptoms, I used Katie McCurdy’s free templates from Pictal Health to help visualize and show the progression of symptoms over time. I wasn’t planning on sending my visuals to my doctor, but it helped me concretely articulate my symptoms and confirm that I was including everything that I thought was meaningful for my healthcare providers to know. I also shared them with Scott to confirm he didn’t think I had missed anything. The icons in some cases were helpful but in other cases didn’t quite match how I was experiencing pain and I modified them somewhat to better match how I saw the pain I was experiencing.

(PS – check out Katie’s templates here, you can make a copy in Google Drive and use them yourself!)

As I spoke with the nurse who was recording my information at intake for imaging, she asked me to characterize the pain. I did and explained that it was probably usually a 7/10 then but periodically gets stronger to the point of causing nausea, which for me is a broken bone pain-level response. She asked me to characterize the pain – was it burning, tingling…? None of the words she said matched how it feels. It’s strong pain; it sometimes gets worse. But it’s not any of the words she mentioned.

When the nurse asked if it was “sharp”, Scott spoke up and explained the icon that I had used on my visual, saying maybe it was “sharp” pain. I thought about it and agreed that it was probably the closest word (at least, it wasn’t a hard no like the words burning, tingling, etc. were), and the nurse wrote it down. That became the word I was able to use as the closest approximation to how the pain felt, but again with the emphasis of it periodically reaching nausea-inducing levels equivalent to broken bone pain, because I felt saying “sharp” pain alone did not characterize it fully.

This, then, is one of the areas where I feel that artificial intelligence (AI) gives me a huge helping hand. I often will start working with an LLM (a large language model) and describing symptoms. Sometimes I give it a persona to respond as (different healthcare provider roles); sometimes I clarify my role as a patient or sometimes as a similar provider expert role. I use different words and phrases in different questions and follow ups; I then study the language it uses in response.

If you’re not familiar with LLMs, you should know it is not human intelligence; there is no brain that “knows things”. It’s not an encyclopedia. It’s a tool that’s been trained on a bajillion words, and it learns patterns of words as a result, and records “weights” that are basically cues about how those patterns of words relate to each other. When you ask it a question, it’s basically autocompleting the next word based on the likelihood of it being the next word in a similar pattern. It can therefore be wildly wrong; it can also still be wildly useful in a lot of ways, including this context.

What I often do in these situations is not looking for factual information. Again, it’s not an encyclopedia. But I myself am observing the LLM in using a pattern of words so that I am in turn building my own set of “weights” – meaning, building an understanding of the patterns of words it uses – to figure out a general outline of what is commonly known by doctors and medical literature; the common terminology that is being used likely by doctors to intake and output recommendations; and basically build a list of things that do and do not match my scenario or symptoms or words, or whatever it is I am seeking to learn about.

I can then learn (from the LLM as well as in person clinical encounters) that doctors and other providers typically ask about burning, tingling, etc and can make it clear that none of those words match at all. I can then accept from them (or Scott, or use a word I learned from an LLM) an alternative suggestion where I’m not quite sure if it’s a perfect match, but it’s not absolutely wrong and therefore is ok to use to describe somewhat of the sensation I am experiencing.

The LLM and AI, basically, have become a translator for me. Again, notice that I’m not asking it to describe my pain for me; it would make up words based on patterns that have nothing to do with me. But when I observe the words it uses I can then use my own experience to rule things in/out and decide what best fits and whether and when to use any of those, if they are appropriate.

Often, I can do this in advance of a live healthcare encounter. And that’s really helpful because it makes me a better historian (to use clinical terms, meaning I’m able to report the symptoms and chronology and characterization more succinctly without them having to play 20 questions to draw it out of me); and it saves me and the clinicians time for being able to move on to other things.

At this imaging appointment, this was incredibly helpful. I had the necessary imaging and had the results at my fingertips and was able to begin exploring and discussing the raw data with my LLM. When I then spoke with the clinician, I was able to better characterize my symptoms in context of the imaging results and ask questions that I felt were more aligned with what I was experiencing, and it was useful for a more efficient but effective conversation with the clinician about what our working hypothesis was; what next short-term and long-term pathways looked like; etc.

This is often how I use LLMs overall. If you ask an LLM if it knows who Dana Lewis is, it “does” know. It’ll tell you things about me that are mostly correct. If you ask it to write a bio about me, it will solidly make up ⅓ of it that is fully inaccurate. Again, remember it is not an encyclopedia and does not “know things”. When you remember that the LLM is autocompleting words based on the likelihood that they match the previous words – and think about how much information is on the internet and how many weights (patterns of words) it’s been able to build about a topic – you can then get a better spidey-sense about when things are slightly more or less accurate at a general level. I have actually used part of a LLM-written bio, but not by asking it to write a bio. That doesn’t work because of made up facts. I have instead asked it to describe my work, and it does a pretty decent job. This is due to the number of articles I have written and authored; the number of articles describing my work; and the number of bios I’ve actually written and posted online for conferences and such. So it has a lot of “weights” probably tied to the types of things I work on, and having it describe the type of work I do or am known for gets pretty accurate results, because it’s writing in a general high level without enough detail to get anything “wrong” like a fact about an award, etc.

This is how I recommend others use LLMs, too, especially those of us as patients or working in healthcare. LLMs pattern match on words in their training; and they output likely patterns of words. We in turn as humans can observe and learn from the patterns, while recognizing these are PATTERNS of connected words that can in fact be wrong. Systemic bias is baked into human behavior and medical literature, and this then has been pattern-matched by the LLM. (Note I didn’t say “learned”; but they’ve created weights based on the patterns they observe over and over again). You can’t necessarily course-correct the LLM (it’ll pretend to apologize and maybe for a short while adjust it’s word patterns but in a new chat it’s prone to make the same mistakes because the training has not been updated based on your feedback, so it reverts to using the ‘weights’ (patterns) it was trained on); instead, we need to create more of the correct/right information and have it voluminously available for LLMs to train on in the future. At an individual level then, we can let go of the obvious not-right things it’s saying and focus on what we can benefit from in the patterns of words it gives us.

And for people like me, with a high (or different type of) pain tolerance and a different vocabulary for what my body is feeling like, this has become a critical tool in my toolbox for optimizing my healthcare encounters. Do I have to do this to get adequate care? No. But I’m an optimizer, and I want to give the best inputs to the healthcare system (providers and my medical records) in order to increase my chances of getting the best possible outputs from the healthcare system to help me maintain and improve and save my health when these things are needed.

TLDR: LLMs can be powerful tools in the hands of patients, including for real-time or ahead-of-time translation and creating shared, understandable language for improving communication between patients and providers. Just as you shouldn’t tell a patient not to use Dr. Google, you should similarly avoid falling into the trap of telling a patient not to use LLMs because they’re “wrong”. Being wrong in some cases and some ways does not mean LLMs are useless or should not be used by patients. Each of these tools has limitations but a lot of upside and benefits; restricting patients or trying to limit use of tools is like limiting the use of other accessibility tools. I spotted a quote from Dr. Wes Ely that is relevant: “Maleficence can be created with beneficent intent”. In simple words, he is pointing out that harm can happen even with good intent.

Don’t do harm by restricting or recommending avoiding tools like LLMs.

This came to mind because he went on a work trip, and I stuck things in the dishwasher for 2 days, and jokingly texted him to “come home and do the dishes that the raccoon left”. He came home well after dinner that night, and the next day texted when he opened the dishwasher for the first time that he “opened the raccoon cage for the first time”. (LOL).

This came to mind because he went on a work trip, and I stuck things in the dishwasher for 2 days, and jokingly texted him to “come home and do the dishes that the raccoon left”. He came home well after dinner that night, and the next day texted when he opened the dishwasher for the first time that he “opened the raccoon cage for the first time”. (LOL).

Recent Comments