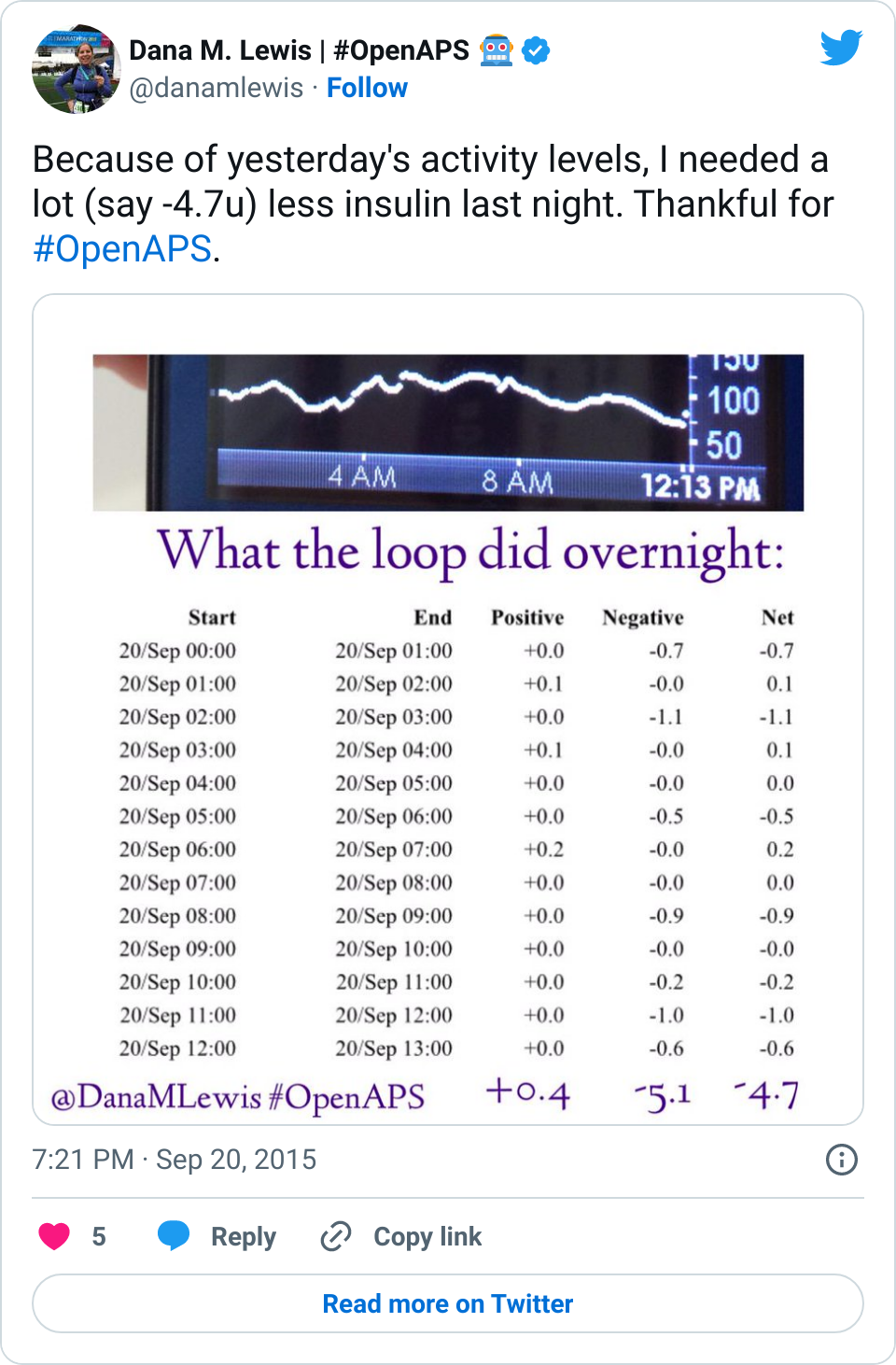

Given that many (7 almost 8!) of us have closed the loop with OpenAPS, and sometimes show pictures of great overnights like the below, and given the fact that diabetes is a complicated, annoying, unfair disease, there is a lot of interest in closing the loop. Scott and I definitely get that, which is why we started the #OpenAPS movement.

I have been asked more and more lately, “Are you going to make this available to less tech-savvy people?” and “Should I build one?”.

The answer to the first question is emotionally hard, because a DIY build of a medical device that auto-adjusts insulin will always involve some technical knowledge – or at the very least, a growth mindset and willing to learn many new things to build a technical knowledge in order to proceed through the murky process of building a not-100%-documented artificial pancreas. You don’t have to be a programmer or an engineer; but you do have to have time and energy to spend learning as well as doing. I say this every day: the DIY part is important.

(And, I know people always want to hear “yes! It’ll be out on X date, and just as easy as installing Nightscout.” But it’s not as easy as installing something like Nightscout and never will be.)

That leads into the second question as an explanation of why it’s not as easy as we would wish:

Even if you have a very technical background, you’ll still spend time learning new languages, new pieces of software, and building pieces of your own. Things will break, things will need to be improved, and you need to have the knowledge of what’s going on and understand the logic of what you’re trying to achieve at each stage in order to be able to troubleshoot both the code part of things and the diabetes part of things.

It is hard. And it is a lot of work.

What you don’t see when someone says they’ve (DIY) closed the loop:

For every “I had such a great night” picture someone posts, that probably represents at least (10?+) hours of working on building or troubleshooting their system. Scott and I have each spent hundreds of hours working with my system, from trouble shooting, to building in new features, to reaffirming that things are all working as planned, etc. That figure should be a bit lower for new people as a result of our efforts, but it will never be as easy as just plugging something in, giving it your weight, and letting it take over. The system only does what you program it to do.

I often say this is “not a set-and-forget” system. And this is also true in the wearability of it. Right now, I use a Raspberry Pi and Carelink USB stick to communicate with my pump. They’re great, but the separate power source I also have to keep charged, plus keeping the USB in range of my pump, plus making sure it’s all working, can be a headache sometimes. (Which is why I’m so glad we made an offline mode, to reduce one of the biggest headaches of using the system.) When I’m on the go during the day, sometimes I don’t take it with me, or I choose to stop and un-power it and resume it when I get home. At this point, I wouldn’t be surprised if most people use it for nighttime use only (at least for the most part). But even with nighttime use only, there’s still constant changing of the code (in some cases daily), tweaking, altering, fixing, breaking, and un-breaking various parts.

Did I mention it was a lot of work?

And does a closed loop prevent all lows and highs? No.

It’s important to realize this is not a cure. I work really hard to do eating soon mode before meals to prevent spikes from the amount of carbs I choose to eat. I still have to test my blood sugar and calibrate my CGMs multiple times a day. I still have to change out my pump site every 2-3 days, and deal with the normal hassles of wonky pump sites, etc. I still have some highs – although the loop helps me handle them and I spend less time above range. And I still have some lows – although usually they’re from human error related to bolusing, the loop helps prevent them from always being a true low and/or blunting the drop so I don’t require as much correction. But diabetes is still a good amount of work, even with a closed loop.

Is it worth it to self-build an artificial pancreas?

This is a personal question. It’s a lot of work, with risk involved.

For me, I have decided and continue to decide that it’s worth it.

But only you can decide if the work and the risk are worth the potential rewards for you.

Recent Comments