A chicken, a fox, and a rattlesnake (mountain) equals an adventure, and one I didn’t think I would get to do this year.

(If you are new to the idea of an ‘exoskeleton’ or you know me and haven’t read my prior post about it, read this post first for context on exoskeletons, my experience with it so far – and more details on why I have been using one for the last few months.)

In August, I bought a Hypershell X Pro exoskeleton, for many reasons. For me, and my individual situation, it has been a huge instrument of freedom, allowing me to get back to some semblance of ‘normal’ volumes and duration of activity (at least for hiking) than I was able to do earlier this year. I put ~250 miles on it within the first 3 months of using it.

Because I’ve been using it, I joined one of the Hypershell groups on Facebook and saw them post about a contest, where they were seeking 10 people who would create user-generated content (aka, take pictures and videos of themselves using it) of their next version, called the Hypershell Ultra. It was centered around doing a ‘challenge’ hike or experience. I applied, thinking I wouldn’t get selected, because 1) I have a condition which is why I’m using it; 2) and/or I already have the Pro so they’d maybe pick people who are all brand new to exoskeletons and 3) I post a lot of trail/adventure pictures but it’s more of nature, not myself, and I don’t have a ton of followers on public platforms – I’m not really an “influencer”. But you don’t get a ‘yes’ unless you apply and try, so I applied anyway. And somehow, I was selected! That means they sent me a Hypershell X Ultra, for free. If I meet all the terms and conditions of the challenge, I get to keep it, if not they’ll want it back. But I was given it to use for free, so factor that in below accordingly (although you might be surprised when you read to the very end of this post).

Why I wanted to do the challenge and try the Hypershell X Ultra

There are a few specific reasons why I really wanted to try the Ultra and was excited about getting access to one. For context, they came out this fall and were marketed at $1,999. That’s…a lot of money. I spent $1,199 on a Pro model which was a lot (but I’m definitely getting my money’s worth from it and am glad I got it). However, as someone who just bought a Pro, I was not interested in buying an Ultra at the $2,000 price point. But I definitely wanted to try it, because the Ultra has some differences from the Pro. Namely, 1) it supposedly has reengineered motors that are more efficient, so they claimed you would get more mileage out of each battery; 2) it has Apple watch support so you don’t have to pull your phone out and unlock it and open the app in order to do certain things while active.

Those, for my use case, would be a nice improvement. In most of my hikes, I have had Scott (my husband) carry the spare battery and we swap it out mid-hike so that I can use as much power as I need. With two batteries, I can do 8-10 mile round trip hikes (and even those with ~3000+ feet of elevation gain) without fully running down the second battery. For me, and the type of adventures I’m doing, one battery isn’t enough (it handles about 4-5 miles of moderate-high intensity flat and maybe 3-4 miles of uphill adventures). So more mileage out of the same two batteries sounded great. That’s also where the watch view comes into play. I found, with the Pro model, that I didn’t like leaving adaptive mode on and instead, having it on Walking mode worked better for me (it still adapts to downhill etc automatically). (More on why about the modes in my other post). But, there are times where I would want to change the mode or would need to check the battery because I’m prone to getting in the zone and charging uphill on my hike and running the battery all the way down to 0, where it dies without warning. There’s no audio or visual cue on the device if you’re actively moving to indicate that you’re about to run the battery down – you just get to the point where it suddenly stops providing assistance and you notice it. Then you stop and change the battery. Which is not a major big deal, but the Hypershell mobile app on iOS has a long-running bug where if you don’t open your app during the hike and you manage to run the battery down to zero…it tracks none of the steps or the mileage. It’s not the only way I’m tracking mileage, but it usually means I lose 4+ miles off the lifetime mileage which I think (because I’ve now done this half a dozen times already!) is going to add up over time and influence my ability to see where I am relative to the expected lifetime of the device. (This is an app issue they should be able to fix with software, they just haven’t yet). TL;DR for that part – the Ultra has a watch app where you can change settings AND see the battery, so I’d have more of a clue without having to pull my phone out to know when I’m getting close to the end of the battery and better plan for it so it doesn’t die halfway up a hilly stretch or that I remember to open the app before that happens.

I also wanted to do it as a motivation to get back out there and do a patented, Dana-and-Scott-special, which is what we jokingly call a chicken and fox adventure day (named after the river-crossing puzzle).

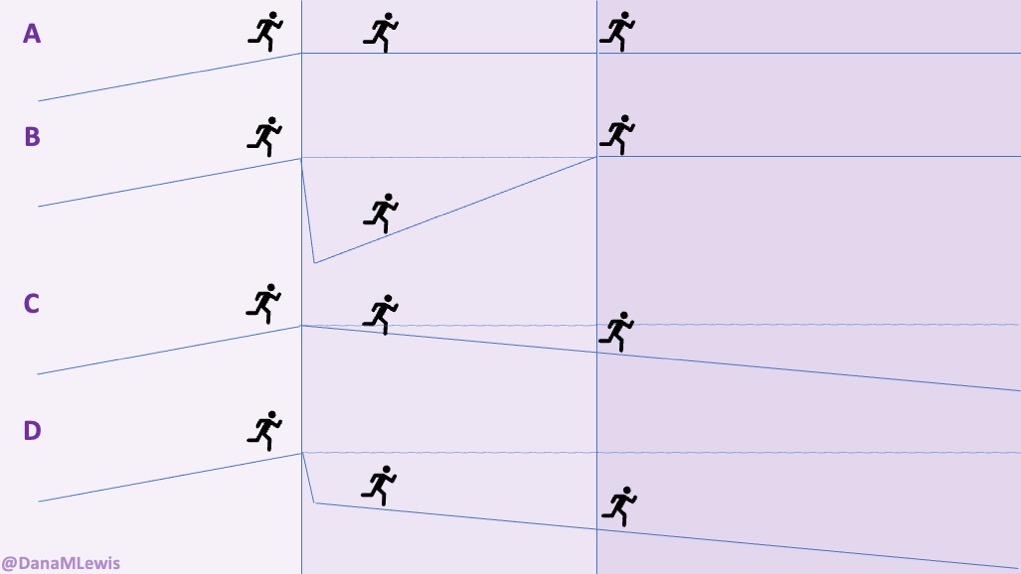

A chicken-and-fox adventure is something we started doing years ago, when I got into ultrarunning. Scott runs, but he doesn’t have the patience for long, flat runs like I do. He’d rather do long distance biking (which I have less patience for), or hike. So on long ultra training days, we’d drive out to the mountains somewhere and I’d pick a running route where Scott could drop me off and then go bike somewhere long and/or interesting, and we’d meet up at the end. Often, that turned into him dropping me off then parking the car at the end of the route, then he’d bike elsewhere, and I’d run my 20-30 miles to the car, grab the car, and drive to wherever his adventure ended and pick him up. Or vice versa with dropping him off at the start and then going for my run. We have had many awesome adventures like this, where “together” we are going out for really cool adventures even though we do them slightly differently, and we have great experiences to share with each other.

In the past year and a half or so…we haven’t had those adventures, because I haven’t been running, and I can’t ride my bike in the same way, and I didn’t feel confident hiking alone for very long. But, since August, my confidence began to grow after a lot of hiking (I’ve put 40,000 feet of elevation gain into my hikes between August and now, all with the Hypershell X Pro exoskeleton).

Thinking about the Hypershell X Ultra “Challenge” made me realize that I could – and wanted – to challenge myself to get back out and do a chicken-and-fox adventure.

The challenge I chose was a chicken and fox adventure on Rattlesnake Mountain (the one in western Washington state in the US)

The adventure I had in mind was a route I have always wanted to do, which is the full end to end Rattlesnake mountain hike. I’ve done parts of it – many people have, especially from Rattlesnake Lake to the Rattlesnake Ledges, which is a famous hike near Seattle that a lot of people do. Rattlesnake Ledges is one of our favorite places to take visitors, so we’ve actually done that twice this year. The other side of the mountain is also a good hike, although more about the wander through the forest. It starts at a mountain biking shared trailhead and meanders up to a few turnaround views (e.g. Grand Prospect) that also makes for a good out and back hike. If you want to hike the entire mountain, you need two cars…or you need someone who will do part of the hike, turn around and hike back down, drive around and meet you at the other side while you hike up and over the rest by yourself.

I had mentioned this hike / idea of an up and over several times, but the idea of hiking by myself made me nervous, especially with my physical abilities changing, because I sometimes need a hand getting up or down really steep, rocky terrain and I’m less sure-footed than most people. However, after ~250 miles of experience hiking with the Hypershell X Pro, my perspective was changing, and I was less nervous hiking in general *and* with the idea of hiking ~6-7 miles by myself up and over the mountain. So I pitched it to Scott and got him to agree to be the chicken* in our chicken-and-fox adventure day, with the plan of starting our hike on the Rattlesnake Ledges side, hiking up to the Ledges, then having him turn around and hike down and drive around to meet me on the other side…while I hiked from Rattlesnake Ledges up and over the remaining segments of the mountain trail by myself!

And that’s what we did (*although Scott claims he was the raft, as the car driver, rather than the chicken or the fox).

PS – if you’re in the area and doing the Rattlesnake Ledges hike, the “Ledges” you come to are actually the “first” ledges – there are two more ledge areas that you can hit! Yes, it’s more climbing, but only a few hundred feet between the ledges and the second ledges, and then up to the third ledges. There are really cool views at each set of ledges where you can see the other ledges, so it’s worth doing on some of your Ledges hikes.

What using the Ultra was like

Like I do for all my hikes, I got out of the car at the parking lot and put it on, which entails clipping the belt around my waist, clipping on each leg strap, and turning it on by pressing the button on the device. It auto-connects to the app and your phone without you having to open your phone each time (which is why, see above, I sometimes manage to run down an entire battery without having the app open so it doesn’t record the mileage in that scenario).

(Also like on most of my hikes, I made it 20 steps from the car before someone I walked by commented on the exoskeleton. It’s always really fun to be able to share with people, because often it’s people who have previous injuries or knee problems or other challenges who have heard about them, watched a video online, but never seen one in person before!)

Based on my experience using the Pro version, I know I like to do most of my flat or slightly uphill efforts on “eco” (green) mode at about 50% power. When I get to hillier sections, I’ll put it into “hyper” (red) mode and toggle the power up as needed for a bigger boost of power on lifting my legs as I climb, but for this hike with smooth terrain with more gradual climbs, I start on my personal defaults (eco, 50%). However, with the Ultra, the ‘re-engineered’ motors mean that the settings I use from my Pro don’t feel strong enough to assist me at the same level. I found myself bumping up to “eco” 75% to feel closer to what I experience with “eco” 50% on the Pro. (I thought maybe this was a one-off, but that does seem to hold true across a couple weeks of using it.)

Like using the Pro, having the Hypershell X Ultra makes it so I could do this full hike. It’s not a short hike: the full Rattlesnake Mountain hike is marked as 10.2 miles but from parking lot to parking lot it is closer to 10.9 miles and I tracked over 3,000 feet of elevation gain. I could do “just” the Rattlesnake Ledges hike (4.3 miles round trip, ~1100 feet of elevation gain), I could do the other side, but my muscles would be too fatigued to safely do a 10+ mile hike, so we wouldn’t even try it without an exoskeleton. And, there’s no way I would have considered doing it alone. Which…I did!

Like using the Pro, having the Hypershell X Ultra makes it so I could do this full hike. It’s not a short hike: the full Rattlesnake Mountain hike is marked as 10.2 miles but from parking lot to parking lot it is closer to 10.9 miles and I tracked over 3,000 feet of elevation gain. I could do “just” the Rattlesnake Ledges hike (4.3 miles round trip, ~1100 feet of elevation gain), I could do the other side, but my muscles would be too fatigued to safely do a 10+ mile hike, so we wouldn’t even try it without an exoskeleton. And, there’s no way I would have considered doing it alone. Which…I did!

Scott hiked up with me to the main Rattlesnake Ledges (the ‘first’ ledges), and we took some pictures, then decided he would hike up with me to the next ledges as well. (In part because I estimated the hiking speed and he would be killing a lot of time waiting on me at the other side, and so he’d have more enjoyable views going up to the extra ledges than hiking through the forest without a view on the other side). We went up to the next ledges, and then he handed over my poles and headed back down the mountain, while I took off up the rest of the mountain…by myself!

(Earlier this year, I found that I needed to use hiking poles on uphill climbs to help me compensate for the very specific leg muscle function I was impaired by. But with the exoskeleton helping target lifting my leg, I have found that I rarely need poles going uphill anymore. Instead, we usually carry them folded up and bust them out of the backpack and use them for stability/confidence on downhill terrain. When Scott turned around, I still had another few thousand feet of elevation gain to go, so I didn’t need the poles, but I took them with me just in case and also so that I had them for the downhill side, which I would do solo.)

We swapped batteries before Scott left, so that I had a fully charged battery for my solo segment. I think at the time I had used only ~40% of the first battery. In retrospect, I should’ve kept the other battery with me, but I didn’t (we put it in his backpack).

I hiked up all the way to East Peak, which is the farthest I had ever been up this side of the trail. I eventually crested onto a ridge where there was a logging area and really clear views on both sides – and the weather had cleared so I had several miles of visibility south to see areas that I had never seen before! I saw one trail runner pass me between this section and Grand Prospect, but otherwise I had over 4 miles solo with no one else in sight…and no concerns about my ability to cover the distance, alone, up in the mountains. Which was so, so, cool. (My only hesitation came with the occasional blowdowns of trees across the trails, one of which was a little challenging to climb over. Otherwise, it was smooth sailing along the trails by myself.)

I made it over to Grand Prospect and took a picture to document being there, because this marked the section of the trail I was familiar with. At this point, I still had 4 miles to go to the trailhead! Right after this, the trail began trailing downhill into the forest and this was where I was glad I had my poles, because although this trail is very smooth (as far as trails go), it had rained pretty heavily the previous two days and was muddy and slippery in a few places. Eventually, as I meandered down and was about 1.7 or so miles from the trailhead, I suddenly noticed my legs felt heavy. I looked down and…no lights. I had run down the full battery on the exoskeleton. Oops (see note above about my partially charged battery being with Scott). Luckily we had planned for Scott to hike up and meet me (rather than sitting around at the car), so I had less than 10 minutes before he reached me and we swapped the batteries back. Ahhhh, that felt so much better. (Although you don’t lift your legs as much on downhill terrain, you still lift your leg and that’s specifically where I have muscle impairment that is really aided by the exoskeleton, so it is night and day even on flat or downhill terrain for me when I use the exoskeleton versus walking without it. So I was glad to have my powered assist back on!)

We finished out the hike at the mountain biking shared trailhead, on the other side of Rattlesnake Mountain. I did it! I was so jazzed. I had been confident about the mileage and elevation, because since August I have done some other hikes in this ballpark of elevation gain and mileage, but it was really rewarding to feel confident enough to do that many miles up on a mountain ridge all by myself and feeling confident enough to deal with whatever situations would arise while hiking solo. And I would not, at this point in my situation, have done this without an exoskeleton.

I previously wrote about some of the benefits of using an exoskeleton, especially for hiking, but two months since writing that post, some of the specific aspects of using it that I wanted to highlight include:

- I can step up and over things more easily. This could be stepping up onto a rock step, or up and over a branch on the trail. These things used to require poles more often; see above where now I very rarely need poles for the uphill even when stepping up and hiking up a long series of rock steps!

- I also less often ‘need’ poles for downhill smooth terrain, like most of the Rattlesnake Ledges hike. I still like having them for trying to move quickly, or for wet/slippery terrain, or bigger step downs, but for rolling smooth terrain I often will go without for the downhill. I didn’t feel like that was even a choice before!

- Because I can get my legs moving back at a reasonable pace for both flat walking and for hiking, I found that I can actually get a good cardiovascular workout again. Meaning, I used to be limited by my legs rather than my cardiovascular system, and my heart rate rarely was elevated and I couldn’t push myself because I was leg-limited. Now, I can actually walk briskly and raise my heart rate intentionally; same for hiking. This is huge for my overall health.

- At the end of hikes and walks, because the rest of my muscles are less fatigued for compensating for the missing muscle action, I am rarely scuffing my feet at the end of walks and hikes the way I was pre-exoskeleton. I also have less fatigue in my muscles, even though I am going farther and longer and working my legs and my cardiovascular system harder! Pre-exoskeleton, I realized that I was limiting us to 8 mile hikes and then more commonly 4-6 mile hikes. Now, I’m back up to regularly wanting to choose 8-10 mile hikes on a regular basis. (And same for elevation: I had limited us down to ~2000 feet of elevation gain hikes for a while, because of fatigue concerns for the end of hikes, and now have no problem choosing >3,000 feet of elevation hikes again!)

All of this was in play during my challenge hike. I actually chose to do this long hike, alone, because I felt like I could do it. I got more physically out of the hike, because I was able to actually locomote and activate my cardiovascular system more, because I wasn’t wasting all my energy just moving my legs. I didn’t need my poles for going uphill. And I didn’t scuff my feet or trip on the entire hike, even though I was out there moving nonstop for 4 hours and 15 minutes!

What using the Ultra is like, compared to the Pro

Remember that my review/experience is skewed by having a lot of experience with the Hypershell X Pro. If you want to read my gushing about how exoskeletons are an instrument of freedom and the best thing since sliced bread for me lately – read my previous post about it. Otherwise, keep in mind this is mainly a comparison between the Pro and the Ultra, rather than never having used an exoskeleton then trying the Ultra.

You should take away from my first blog post (really, read it first if you haven’t!) and this one so far that exoskeletons are awesome and for people like me, they are a huge instrument of freedom. I never want to be without one, especially as long as I’m in whatever situation I’m in where my muscles work differently than they used to. That being said, I do see a lot of people asking online about the Ultra, the Ultra versus other models, etc, and I want to explain – from my perspective – what the differences are. And this needs a major caveat: my experience is 1) that of a person with some kind of condition that affects my leg muscles and 2) that of a person who personally bought and heavily used the Pro model before being given free access to the Ultra. Then read the below two sections because I’m going to give specific answers to what you should consider getting (or not) if you already have an exoskeleton versus what you should consider if you don’t already have one.

The difference between no exoskeleton and the Pro is probably 5x stronger than the difference between the Pro and the Ultra. The Ultra does have re-engineered motors supposedly causing it to be more efficient…but in my use case (which is likely different than the average person – remember my default ‘walking’ mode is eco 50% which is a lot higher than most people’s) I found that I had to bump the power up so much higher on the Ultra – to default eco 75% for just flat walking, and often 75% hyper mode for hills, too, then also often going up to 100% hyper for bigger hills. I rarely did that on the Pro. It is possible that I’m getting more mileage per battery, but I still don’t feel confident that it is because it’s more efficient or if they changed the power settings relative to each of those modes so I’m not using as much power as I was before. And while most people maybe wouldn’t notice that, I actually do. Because of how my leg muscles are specifically impaired, I can absolutely tell the difference between these. So I was less excited after using it, because of those factors for my unique situation.

The watch mode IS a game changer, though, for people like me who are busy hiking and not looking at our phones. It gives you a way to quickly turn adaptive mode on and off or switch between eco and hyper if you’re not familiar with the on-device button way of doing it (although it’s easy to learn: it’s a two second long press to switch you back and forth). But for me, the biggest benefit is having the watch app to show me the battery level! That helps me better see as I’m getting to the end of one battery as I often do, so I can remember to open my app (until they fix that bug) and also to look at where I am on the hike and decide if I want to go ahead and swap it out if I’m in the middle of a big steep section and don’t want to have to stop mid-climb when it suddenly dies. I did see a post somewhere that the watch app will eventually come to the other models (I hope so!), in which case this will also be a selling point for the other models rather than a differentiator for the Ultra. Update: as of early December 2025, the watch app now supports all models! So this is no longer a key differentiator.

The Ultra does look different: instead of orange and silver reflector material on the leg straps and waist belt, it is primarily black. The bars that extend down your legs are also black, because they’re the lighter carbon fiber material. I think aesthetically, the Ultra is a little more ‘subtle’ because of those color changes, especially when you’re wearing it against pants. In summer, when it’s against bare legs with shorts, I think it’ll be noticeable the same amount, but because I got access to the Ultra when I started wearing longer pants for hikes and walks this fall, it does feel like it’s less visually noticeable. Weight-wise, though, I don’t notice a difference from the carbon fiber material and the Ultra being slightly lighter overall weight than the Pro. This is something I actually considered about whether to buy the Pro versus the “Carbon” version originally..but I actually am not bothered by the Pro weight at all. The weight difference is maybe there, but because the Pro weight doesn’t phase me at all, it doesn’t feel like a big differentiator to me. However, I do see some people online who perceive the weight of the Pro to be a factor for them, so I’m guessing they’d benefit more from the lighter weight than I do.

Takeaways for those considering an exoskeleton if you don’t already have one

If you’re on the fence about getting an exoskeleton – yes, you should get one. Especially for those of us who have conditions that have changed our activity levels and patterns – it really is a game changer. The question shouldn’t be “should I get one” but “which one should I get”.

And based on my experience, I look at the math on battery, power output, and my experiences with both (see the chart on my previous post if you want to breakdown all the variables for the 3 main models outside of Ultra), and say…I still think the Pro is the best deal, for most people with the current pricing models.

- The $200 difference is absolutely worth it for the higher output and second battery that you get with the Pro versus the lower “Go” model.

- I chose the Pro originally because I didn’t think the main difference between the Pro and the Carbon, the weight difference, was worth $500. After using it for several months and after trying the carbon fiber (lighter weight) based Ultra, I still think that’s true.

- I originally thought, before trying it, that maybe the extra mileage from the ‘re-engineered, more efficient motors’ on the Ultra would be worth it, so it would be a question between the $1200 Pro and the $2000 Ultra, with it being worth it IF you were someone like me who was really putting a lot of miles in and was regularly running down 1.5-2 full batteries per activity. But…after using it… in the current iteration, I don’t think that’s the case. (Again, my perspective might be skewed by ‘how high’ I run my default power levels, starting at eco 50% most of the time. So maybe that mileage boost is more for people who don’t by default use as much power as I do for all mileage. People who are fine with lower power output and are high mileage probably would like the Ultra.)

- I still think most people are best suited by the “Pro” model. And if you’re like me and really putting the mileage in, it would be cheaper to get the Pro and later buy an extra battery or two than it would be to go for the Ultra. Unless you’re not like me and are a lower power need and also maybe someone who would notice the weight difference when wearing it.

TL;DR: you should absolutely get an exoskeleton. But, for most people, see above – go with the “Pro” unless you have specific reasons (e.g. lots of mileage and/or strongly preferring the slightly lighter weight of the device) to choose the Ultra.

Takeaways for those considering an Ultra if they already have another model

I think the same outline above applies here, which is that most people who have a Pro or a Carbon likely won’t benefit enough from the Ultra to justify an upgrade while theirs is still in good working order. I think the people who would benefit would be if you started on a “Go” model which only came with one battery and doesn’t put as much power out. Then, a switch to the Ultra is a reasonable shift for a second version exoskeleton, if you can afford it: otherwise going to the Pro gives you likely 90% of the benefit of the switch. However, a Pro to Ultra or a Carbon to Ultra doesn’t make as much sense until you wear down your existing exoskeleton and it reaches end of life, or you are someone with a Pro who really needs a lighter weight version and uses lower power output but still runs the battery down, in which case you might be the use case that is suited to the Ultra. But if you’re not in those situations, you may not have as much need to upgrade until your existing one reaches its end of life.

And who knows, maybe subsequent firmware and software upgrades will change the Ultra. If they manage to change the power levels back to something that better matches the Pro where I have more range to use the upper end of the power *and* get more mileage per battery? Then I will be a huge fan and encourage people to factor that into their decisions. But until then, see above.

—

TL;DR: I love exoskeletons, they’re an instrument of freedom. I paid $1,200 in August 2025 for a Hypershell X Pro exoskeleton and love it (still love it). In late October/early November, I was given for free a Hypershell X Ultra exoskeleton after being selected for the Hypershell X Ultra Product Explorer program and have been using it and comparing it for the last several weeks. I love the opportunity and appreciate being chosen in the explorer challenge program so I could try it, and because it motivated me to head out on a big chicken-and-fox adventure up and over the full length of Rattlesnake Mountain, which I wouldn’t be able or willing to do without an exoskeleton to support my adventuring.

TL;DR: I love exoskeletons, they’re an instrument of freedom. I paid $1,200 in August 2025 for a Hypershell X Pro exoskeleton and love it (still love it). In late October/early November, I was given for free a Hypershell X Ultra exoskeleton after being selected for the Hypershell X Ultra Product Explorer program and have been using it and comparing it for the last several weeks. I love the opportunity and appreciate being chosen in the explorer challenge program so I could try it, and because it motivated me to head out on a big chicken-and-fox adventure up and over the full length of Rattlesnake Mountain, which I wouldn’t be able or willing to do without an exoskeleton to support my adventuring.

In terms of getting set up and putting it on, it’s very straight forward. It gave me a starting suggestion to use for the waist size. I used that (and have never changed it), tightened up the waist strap and leg straps, and it was good to go from there. Once I got the waist strap tightened, I haven’t had to re-tighten or change that. I have had to tweak the leg straps a little bit here and there, partially because of how it slides around on my leg (see below re: sweating, chafing, and wearing in the summer as opposed to wearing it over a layer of clothing), but it’s quick and easy to tighten the leg strap or loosen it when needed and not a big deal adjustment wise. I did read a few people saying it slips down their hips and they got suspenders to help, but I haven’t had that experience (I’m female, so I have plenty of hip bone for it to rest against, and maybe that’s in part what makes the difference?). The first time I put it on, because I was adjusting straps, I put it on while sitting at the edge of a chair and getting everything set up and tightened, then stood up and tweaked the straps, then turned it on and began using it. Now, I can grab it and put on the waist belt while standing, then slightly lean over and attach each leg strap (so I don’t have to sit down to put it on). Because it carries the battery in the back and the design also has the support bar around the back, it’s not really comfortable to sit with for long if you want to lean back against the back of the chair, but it’s fine if you’re sitting down briefly on something (a chair, a bench, etc) if you’re not trying to lean back or sit up against the back of anything.

In terms of getting set up and putting it on, it’s very straight forward. It gave me a starting suggestion to use for the waist size. I used that (and have never changed it), tightened up the waist strap and leg straps, and it was good to go from there. Once I got the waist strap tightened, I haven’t had to re-tighten or change that. I have had to tweak the leg straps a little bit here and there, partially because of how it slides around on my leg (see below re: sweating, chafing, and wearing in the summer as opposed to wearing it over a layer of clothing), but it’s quick and easy to tighten the leg strap or loosen it when needed and not a big deal adjustment wise. I did read a few people saying it slips down their hips and they got suspenders to help, but I haven’t had that experience (I’m female, so I have plenty of hip bone for it to rest against, and maybe that’s in part what makes the difference?). The first time I put it on, because I was adjusting straps, I put it on while sitting at the edge of a chair and getting everything set up and tightened, then stood up and tweaked the straps, then turned it on and began using it. Now, I can grab it and put on the waist belt while standing, then slightly lean over and attach each leg strap (so I don’t have to sit down to put it on). Because it carries the battery in the back and the design also has the support bar around the back, it’s not really comfortable to sit with for long if you want to lean back against the back of the chair, but it’s fine if you’re sitting down briefly on something (a chair, a bench, etc) if you’re not trying to lean back or sit up against the back of anything.

AI often gives us new capabilities to do these things, even if it’s different from the way someone might do it manually or without the disability. And for us, it’s often not a choice of “do it manually or do it differently” but a choice of “do, with AI, or don’t do at all because it’s not possible”. Accessibility can be about creating equitable opportunities, and it can also be about preserving energy, reducing pain, enhancing dignity, and improving quality of life in the face of living with a disability (or multiple disabilities). AI can amplify our existing capabilities and super powers, but it can also level the playing field and allow us to do more than we could before, more easily, with fewer barriers.

AI often gives us new capabilities to do these things, even if it’s different from the way someone might do it manually or without the disability. And for us, it’s often not a choice of “do it manually or do it differently” but a choice of “do, with AI, or don’t do at all because it’s not possible”. Accessibility can be about creating equitable opportunities, and it can also be about preserving energy, reducing pain, enhancing dignity, and improving quality of life in the face of living with a disability (or multiple disabilities). AI can amplify our existing capabilities and super powers, but it can also level the playing field and allow us to do more than we could before, more easily, with fewer barriers.

Recent Comments