We’ve been quiet on the blogging front (yes, I admit, I blogged!) because we’ve been busy closing the loop. (We’re always active on Twitter, though – make sure you watch #DIYPS on Twitter for more real-time updates in between blog posts, and you can follow @ScottLeibrand and @DanaMLewis.)

That’s right.

Closing the loop.

It feels good to say that :).

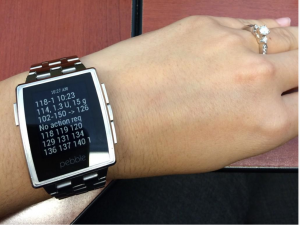

We’re submitting a research proposal to Medtronic to get access to their research device that will enable us to send commands to my insulin pump. These commands will be generated from #DIYPS. Because that would remove the “human in the loop” component that’s a current part of #DIYPS (i.e. me pushing the pump buttons), that would move #DIYPS from being not an artificial pancreas to a closed loop artificial pancreas system.

This is not what we imagined we would do when we set off nearly a year ago to do this work (make a louder CGM alarm system, enable remote monitoring, etc.), but this is awesome!

And, in the true #wearenotwaiting spirit, we’re not waiting for the research device to start this phase of our work. We got started with this phase of our research by getting a Raspberry Pi and hooking it up to the Carelink USB and sending commands to a test Medtronic pump.

(Note: this pump is not hooked up to my body! There is no insulin in it! We’re just testing to see how data can be read off the pump & fed into #DIYPS. There will be many tests with a pump not connected to my body and many safety checks and stages before we would get anywhere near to allowing this to run under waking, close observation let alone under observed sleeping conditions. Stay tuned for more on this later.)

We’ve been having many discussions with the other developers of Nightscout, and end users in the CGM in the Cloud Facebook group around this topic. Scott and I are both passionate about the open source part of our project and being open and transparent every step of the way. We’ve been learning a lot from #DIYPS and have some key features that we’re putting back into the overall Nightscout platform as a result. We’re calling this “#DIYPS-Lite”, or the “wip/iob-cob” branch of Nightscout. (This is not what the main community is using, it’s still an advanced test branch, but enables more advanced users to implement and take advantage of some of these features, like net IOB and COB.) We’ve also been contributing to the roadmap of Nightscout; as of this past weekend, we helped map out the priority list to show what are priorities of some of the core developers (including Scott and I); what’s currently being worked on; and what’s on the ‘backlog’ as a project we’re all interested in and is important to the community, but no one’s had a chance to jump in and start it yet.

Back to the closed loop update

We won’t be releasing any closed-loop systems to the public any time soon, because that would mean distributing an untested medical device system that controls administration of a potentially lethal drug (insulin), which the FDA (and anyone in their right mind) would (rightly) frown on.

Instead, we want to open up our process of developing such systems, so that other researchers (including independent ones like us, and those inside traditional research labs and companies) have a roadmap to follow for how to safely put together and test an open-source artificial pancreas system. The more people and companies we have developing such systems, sharing their results, and learning from each other’s work, the closer we’ll be to having a system that could indeed be proven safe and effective to the FDA’s satisfaction, and eventually released to the public. In the end, we suspect the companies and research labs developing APS systems will be the ones to commercialize them, but we are confident that our efforts will accelerate those timelines and result in a more dynamic, innovative T1D medical device ecosystem that will provide a bridge to a true cure.

We are hoping that we can show the world how open source innovation and new regulatory paradigms can deliver safe and effective results for people living with T1D faster than traditional medical device development and traditional regulation. By doing so, we can change how all successful medical device companies approach interoperability, and get to a world where the latest ideas, algorithms, and software can be made available to everyone with T1D, regardless of what hardware they’re using.

Recent Comments