I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking lately about how to optimize exercise and physical activity when your body doesn’t do what it’s supposed to do (or what you want it to do). We don’t always have control over our bodies; whereas we do, sometimes, have control over our actions and what we can try to do and how we do physical activity. A lot of my strategies for optimizing exercise and physical activity have actually been updating my mental models, and I think they might be useful to other people, too.

But first, let me outline a couple of scenarios and how they differ so we have a shared framework for discussing some of the mental strategies for incorporating activity and exercise into life with chronic diseases like autoimmune diseases.

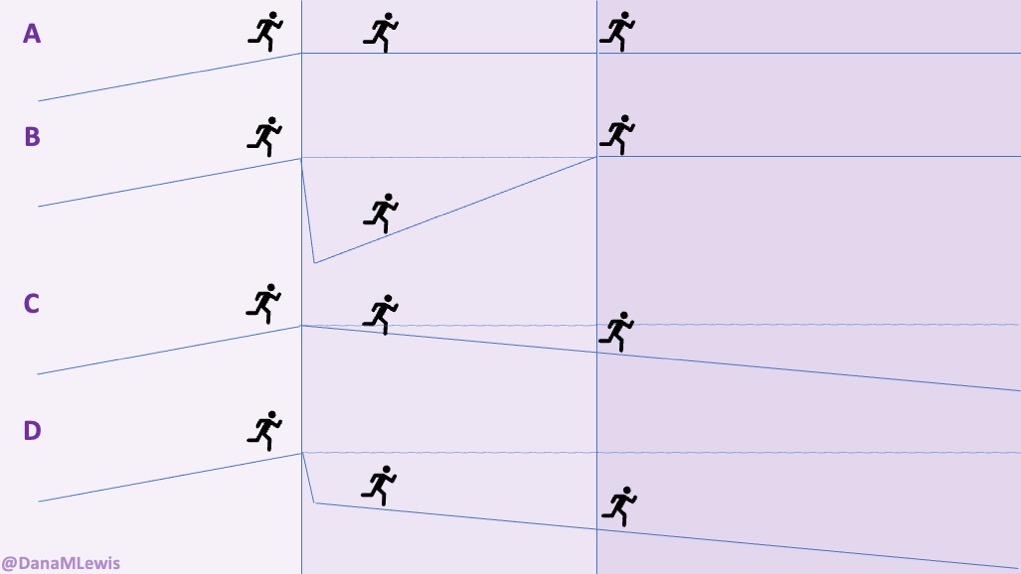

Let’s imagine you’re running and you come to a cliff.

- In scenario A, there’s a bridge across to the other side at the same level. It’s no big deal to continue running across and continue on your way.

- In scenario B, there’s no bridge, and you tumble off the cliff, but then you are able to (eventually) work your way back up to the other side at the same level as the person who could just stroll across the bridge.

- In scenario C, there’s no bridge but the cliff isn’t as steep of a drop off; instead, it’s like a 2% railroad grade trail sloping away and down. You continue down it, but you end up well below the other side where a bridge would’ve connected, and there’s no way up to that level. The longer you go, the farther you are from that level.

- In scenario D, there is a cliff that you fall off of, and you pick yourself up and keep going but it’s on that 2% railroad grade sloping away and down. Like scenario C, you end up well below – and even farther below – where you would have been if the bridge had been there.

This is basically illustrative of the different types of situations you can find yourself in related to health status.

- If all is well, you’re in scenario A: no bumps in the road, you just carry on.

- Scenario B is like when you have a short-term injury or accident (like breaking your ankle or a toe) where you have a sudden drop in ability but you are able to build back up to the level you were at before. It may take longer and feel like a hard slog, but usually you can get there.

- Scenario C is when you have a chronic disease (or are experiencing aging over time) where there’s small changes in the situation or in your ability. Because of these factors, you end up below where you maybe would like to be.

- Scenario D is when there’s an acute situation that triggers or results in a significant, sudden drop followed by a chronic state that mimics the downward 2% small change slope that adds up significantly over time, meaning you are well below compared to where you would like to be.

My personal experiences and living in Scenario D

I have dealt with scenario B via a broken ankle and a broken toe in past years. Those stink. They’re hard. But they’re a different kind of hard than scenario C and scenario D, where I’ve found myself in the last few years and more acutely, I now am clearly operating in scenario D: I have had an acute drop-off in lung function and have autoimmune diseases that are affecting my ability to exercise, especially as compared to “before”. In fact, I keep having cycles of scenario D where my VO2 max drops off a cliff (losing a full point or more) within 2-3 days, then plateaus at the low level during the length of that round of symptoms, before maybe responding to my efforts to bring it back up. And it doesn’t always go back up or respond to exercise the way it used to do, “before”, because well, my lungs don’t work like they used to.

It’s been pretty frustrating. I want to keep building on the hard work I’ve put into my last 2-3 years of ultrarunning. Last year around this time, I ran a personal best 100k (62 miles) and beat my brother-in-law’s 100k time. I’m pretty proud of that because I’m pretty slow; but in ultras if you pace well and fuel well, you can beat faster runners. (As opposed to much shorter distances where speed matters more!).

This year, however, I can barely trek out – on the best day – for a 4 mile run. I had originally envisioned that, due to my fitness level and cumulative mileage build up, I would be able to train for and run a fast marathon (26.2 miles / ~42k) this spring, and that was supposed to be what I was training for. (Fast being “fast for me”.) But instead of running ~30-40 miles a week, I have been running 8-16 miles per week and have only clocked in half of the total mileage I had done by this point last year. Argh. I didn’t expect to do as much overall, but 210 instead of 420 miles by the beginning of April shows how different it’s been and how limited I have been. I’ve dropped the scheduled plan for marathon training – or any hopes of ultra training this year, unless something changes drastically in a positive way that I’m not expecting.

I finally realized that comparing my abilities to “before” is the crux of a lot of my angst. It is a little hard when you realize over time (scenario C) that you can’t do something that you think you should be able to. For example, me trying to run fast: it just has never worked the way training to run fast seems to work for other people. Eventually, in “before times”, I had settled into a strategy of running far, but doing so more slowly, and that’s turned out to be way more fun for me. But when you have an acute adjustment in ability that isn’t like scenario B (e.g. you can expect to regain strength/function/ability over time), it’s really hard to wrap your brain around. And comparisons to ‘before’ feel inevitable. They’re probably part of the grieving process in recognizing that things have changed. But at some point, it’s helpful to recognize and picture that you ARE in scenario D. This includes grappling with and accepting the fact that something has changed; and you likely do not have control over it.

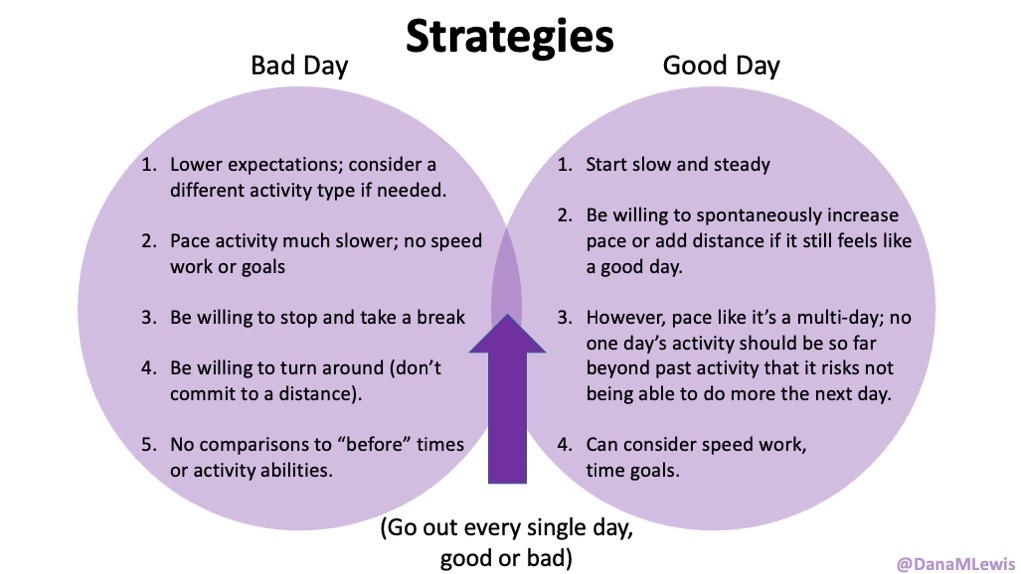

I have updated my mental model with some strategies, to help me frame and recognize that on bad days, I don’t have to push myself (even if deep down I want to, because I want to rebuild/gain fitness to where I “should” be) – and that I should save that strategy for “good” days.

Here’s what I’ve landed on, for general strategy approach, which applies to whatever activity that I ultimately choose for the day:

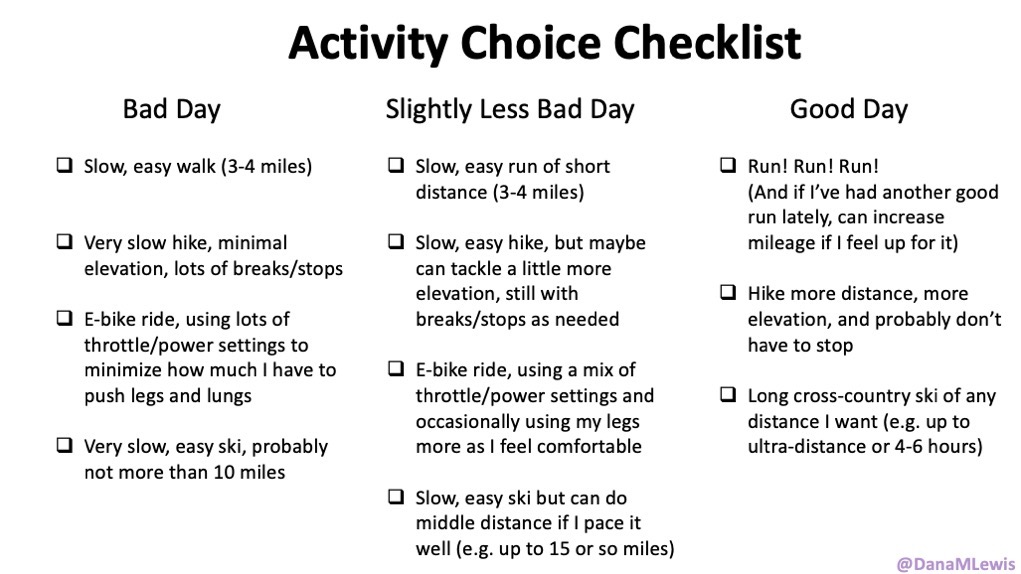

The other thing, in addition to comparing distance, time and pacing to “before” abilities, that I have struggled with, is not having a training plan or schedule. Because my ‘good’ days (where my lungs do not seem to limit my activity) are unpredictable, I can’t build a training schedule and build up mileage/ability the way I used to. Ultimately, I have had to land on a strategy that I don’t like but accept is the most feasible one for now (suggested by Scott): have a “checklist” of activities for my ‘good days’, and have a checklist of activities for my ‘bad days’. This has helped me separate my before-desire for running being my primary activity (and thinking about my running ‘schedule’ that I wish I could go back to), and instead be more realistic on the day-of about what activities are ideal for the type of day I’m actually dealing with.

For example, on my worst days, I cannot run for 30 seconds without gasping for breath and any type of intensive activity (anything more than a really slow meandering walk or a few seconds of a really slow run) feels terrible. Walking feels yuck too but it’s tolerable when I go slow enough, even though my lungs still feel physically uncomfortable inside my rib cage. On medium bad days, I maybe can do a slow, easy, short run with 20 seconds run intervals; a walk; an easy super slow hike with lots of stopping; or an e-bike ride; or easy pace cross-country skiing (when it was winter). On good days? I can do anything! Which means I can hike more elevation at clippier paces (and I can actually push myself on pace) or run with some modicum of effort above a snail’s pace or run a snail’s pace that doesn’t hurt for 30 second intervals. Those are my favorite activities, so those are high on my list (depending on whether it’s the weekday or weekend) to try to do when I’m feeling good. On the bad days or less good days, I take whatever activity is available to me however I can get it.

There are tons of activities so if you’re reading this, know that I’m making this list based on MY favorite types of activities (and the climate I live in). You should make your list of activities and sort them if it’s helpful, to know which ones bring joy even on the worst days and those are what you should prioritize figuring out how to do more of, as the days permit.

Some of this stuff maybe seems “duh” and super intuitive to a lot of people, especially if you’re not living in Scenario D. Hello to everyone in Scenario A! But, when you’ve been thrust off a metaphorical cliff into Scenario D, and there’s no way to do what you did “before”, figuring out how to pace and push yourself to regain what fitness you can OR preserve basic health functionality as long as you can…it’s all an experiment of balancing what amount of activity pushes you in a positive way and builds strength, fitness and health and balancing against going over the point where it causes short-term harm (to the point where it impedes your activity the following days) and/or long-term harm (e.g. further hurts your lungs or other body parts in a way that is either irreversible or hard to recover from).

The pep talk I wish I got that I’m giving to you now

Before I lived in Scenario D (lung stuff), I lived a lot in Scenario C: running with type 1 diabetes AND celiac AND Grave’s AND exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (which means I have to juggle glucose management while only eating gluten free and calculating and eating enzymes for any of that gluten free food I eat as fuel while running) was a lot to juggle, in of itself. I often thought about how much I was juggling while running along, while recognizing that a lot of that juggling was invisible to the outside. Which made me think and observe that even though I feel like every other runner was flying by me and not dealing with the exact same set of balls to juggle; some of those runners WERE probably juggling their own health stuff and limitations, too (or are parents juggling jobs and kid schedules and running, etc). Everyone’s got baggage that they’re carrying, of some sort, or are juggling things in a different way. So, juggling is hard. Kudos to everyone for getting out there for juggling with what they’ve got.

But especially now in Scenario D, it’s even more important to me that it’s not about being out there and running certain paces or hiking certain distances: it’s getting out there AT ALL which is the entire point. And I’ve made it my mission to try to compliment people for getting out there, when it feels like it’s appropriate to do so.

Last week, I was handed the perfect opportunity, and it turned out to be the best conversation I’ve had in a long time. A woman was coming uphill and commented that I had not forgotten my hiking poles like she had. I said yeah, they make a difference going downhill as well as up! She said something about huffing and puffing because she has asthma. DING DING: opportunity to celebrate her for being out there hiking uphill, even with asthma. (I pretty much said that and complimented her). She and Scott were trading comments about it being the beginning of hiking season and how they had forgotten their hiking poles and we told them we were making a list throughout the hike of everything else we had forgotten. They mentioned that they were 70 (wow!) and 75 (wow!) and so they didn’t think they needed walkie talkies because they would not separate on the trail (one of the things that we forgot to bring in case Scott mountain-goated-ahead of me on the trail at any point). We gave them our sincere compliments for being out there hiking (because, goals! I am aiming hard and working hard to get to the age of 70 and be able to hike like that!). She talked about it being hard because she has asthma and was struggling to breathe at first before she remembered to take her albuterol…and I pointed out that even if she was struggling and had to stop every few minutes, it didn’t matter: she was out there, she was hiking, and it doesn’t matter how long it takes! She thought that was the best thing to hear, but it was really what I try to tell myself because I love to hear it, too, which is celebrating going and not worrying about pace/slow/whatever. I told her I had a lung condition too (she’s the first stranger I’ve ever told) and she asked if I was stopping every 2 minutes and whether I had taken an inhaler. I explained most of my lung condition doesn’t respond to an inhaler but that yes, I too had to stop and catch my breath. But it was an awesome, gorgeous day and worth hiking in and that I was glad I had gone up. Ultimately, she said a lot of things that made it seem like my shared experience helped her – but in turn, seeing her and talking to her helped ME just as much, because it reminded me that yes, everyone else is juggling things while hiking too. And it’s really not about speed/pace/time; it’s absolutely about being out there and enjoying it. (And helped me recognize that hiking poles are an instrument of freedom.)

So that’s what I’m trying to do: I’m trying to move beyond the comparison from what I did before, and simply compare to “am I going out at all and trying”. Trying = winning; going = winning, and that’s the new mental model that has been working really well for me as I spend more time in Scenario D.

—

PS – if you read this and are in a similar situation of Scenario B, C, or D and want a virtual high five and to feel “seen” for what you’re working through – feel free to comment here or email any time. I see you going out and trying; which means you’re winning! And I’m happy to give a virtual comment the way I am trying to give comments out on the trails and compliment folks for the process of being out moving through the world in all the ways that we can, however we can.

Thank you so much for sharing this. I also have asthma and I am aging… I really love how you broke down the scenarios. And I love your ending.

Thanks for your comment, Margaret! Let me know if you have any tips or discover any tricks in the future – I know I can learn a lot from people with asthma & more experience juggling uncooperative lungs with exercise.