When dealing with chronic illnesses, it sometimes feels like you have less energy or time in the day to work with than someone without chronic diseases. The “spoon theory” is a helpful analogy to illustrate this. In spoon theory, each person has a certain number of “spoons” representing their daily energy available for tasks including activities of daily living, activity or recreation activity, work, etc. For example, an average person might have 10 spoons per day, using just one spoon for daily tasks. However, someone with chronic illness may start with only 8 spoons and require 2-3 spoons for the same daily tasks, leaving them with fewer spoons for other activities.

I’ve been thinking about this differently lately. My priorities on a daily basis are mixed between activities of daily living (which includes things like eating, managing diabetes stuff like changing pump site or CGM, etc); exercise or physical activity like walking or cross-country skiing (in winter) or hiking (at other times of the year); and “work”. (“Work” for me is a mix of funded projects and my ongoing history of unfunded projects of things that move the needle, such as developing the world’s first app for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency or developing a symptom score and validating it through research or OpenAPS, to name a few.)

As things change in my body (I have several autoimmune diseases and have gained more over the years), my ‘budget’ on any given day has changed, and so have my priorities. During times when I feel like I’m struggling to get everything done that I want to prioritize, it sometimes feels like I don’t have enough energy to do it all, compared to other times when I’ve had sufficient energy to do the same amount of daily activities, and with extra energy left over. (Sometimes I feel like a raccoon juggling three spoons of different weights.)

As things change in my body (I have several autoimmune diseases and have gained more over the years), my ‘budget’ on any given day has changed, and so have my priorities. During times when I feel like I’m struggling to get everything done that I want to prioritize, it sometimes feels like I don’t have enough energy to do it all, compared to other times when I’ve had sufficient energy to do the same amount of daily activities, and with extra energy left over. (Sometimes I feel like a raccoon juggling three spoons of different weights.)

In my head, I can think about how the relative amount of energy or time (these are not always identical variables) are shaped differently or take up different amounts of space in a given day, which only has 24 hours. It’s a fixed budget.

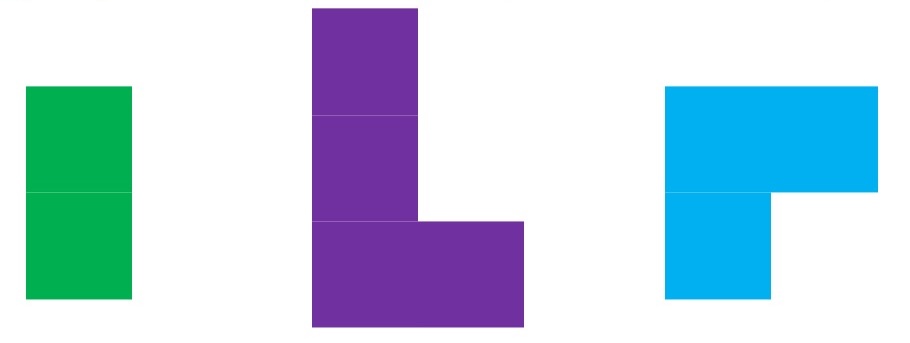

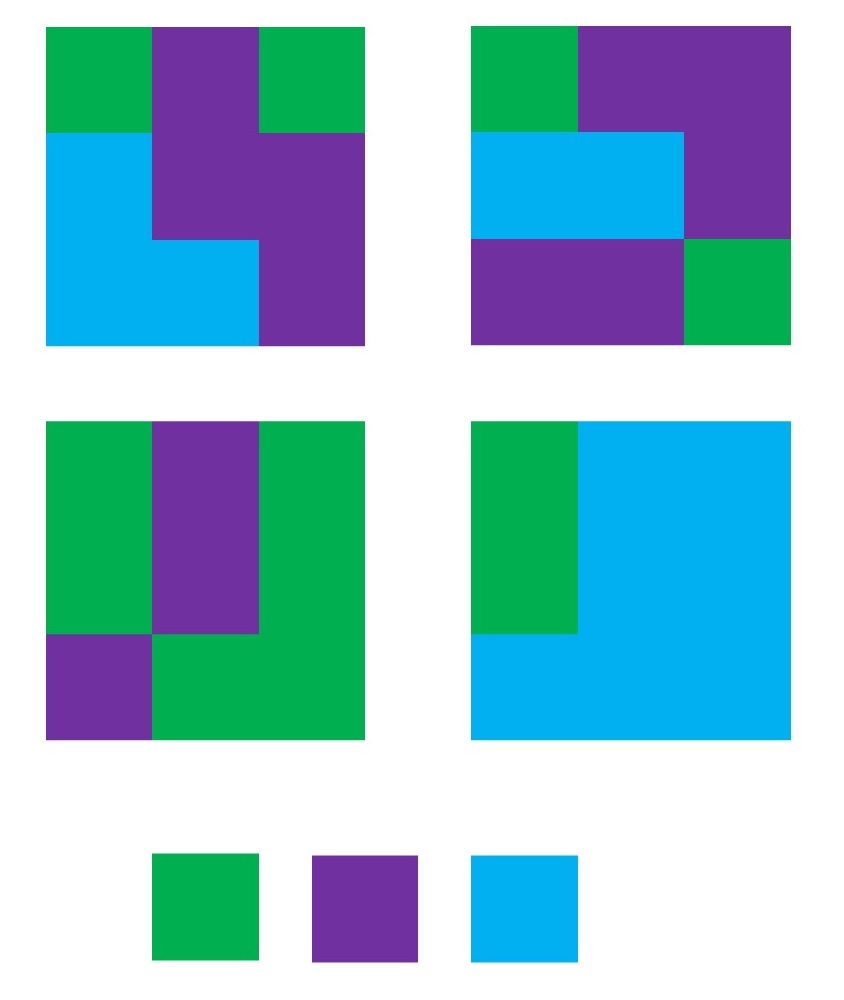

I visualize activities of daily living as the smallest amount of time, but it’s not insignificant. It’s less than the amount of time I want to spend on work/projects, and my physical activity/recreation also takes up quite a bit of space. (Note: this isn’t going to be true for everyone, but remember for me I like ultrarunning for context!)

ADLs are green, work/projects are purple, and physical activity is blue:

They almost look like Tetris pieces, don’t they? Imagine all the ways they can fit together. But we have a fixed budget, remember – only 24 hours in the day – so to me they become Tangram puzzle pieces and it’s a question every day of how I’m going to construct my day to fit everything in as best as possible.

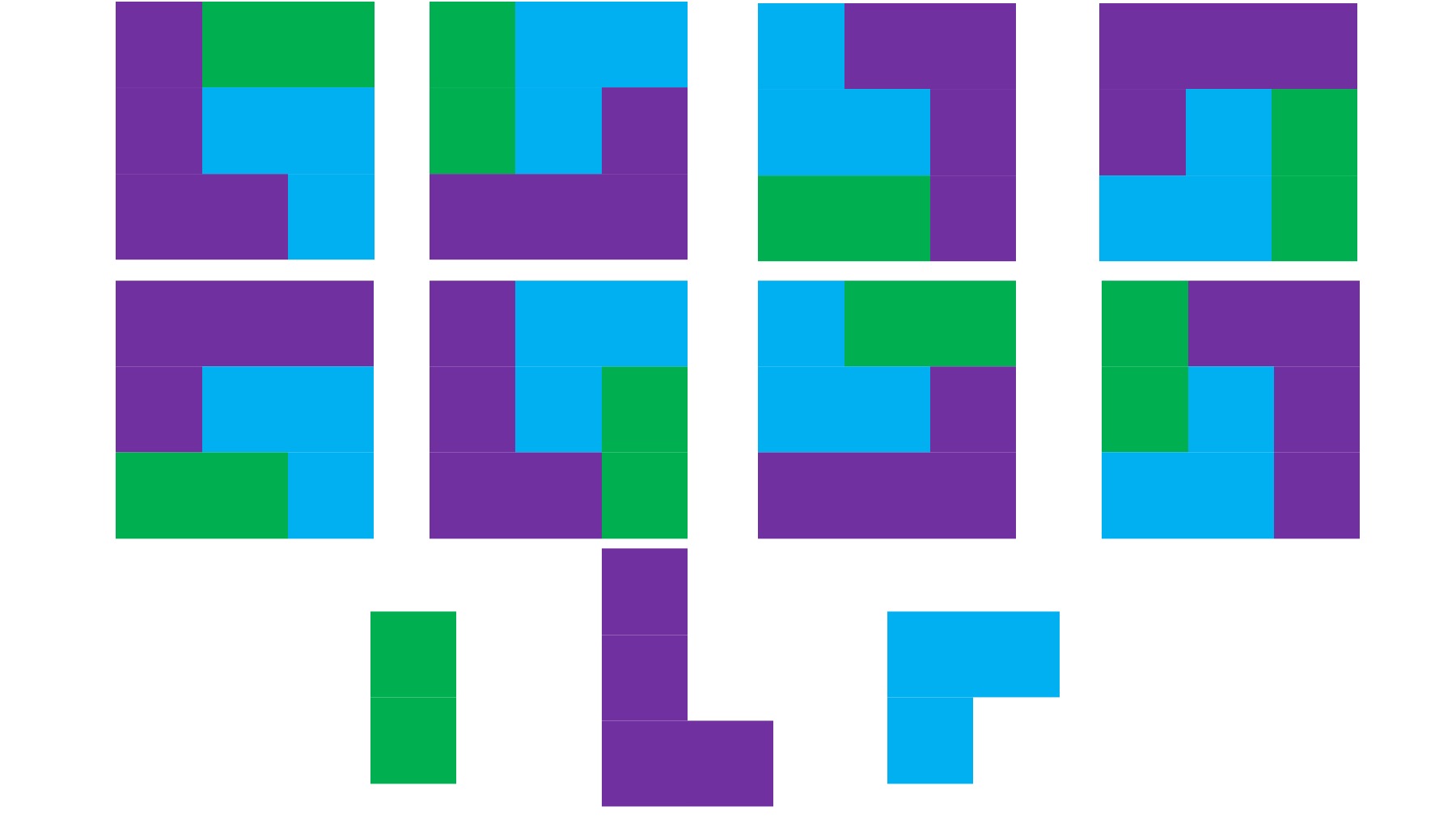

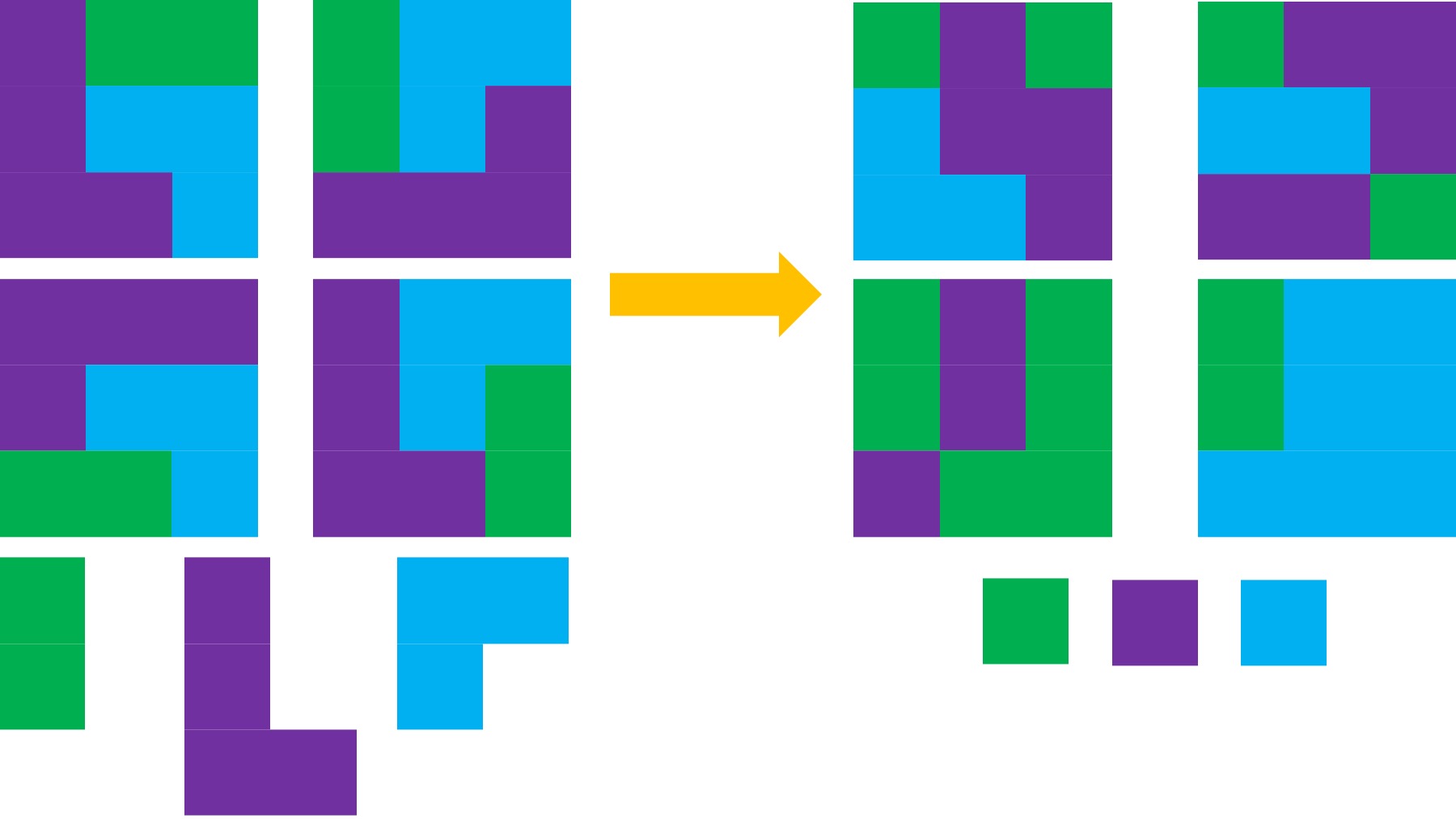

Preferably, I want to fit EVERYTHING in. I want to use up all available time and perfectly match my energy to it. Luckily, there are a number of ways these pieces fit together. For example, check out these different variations:

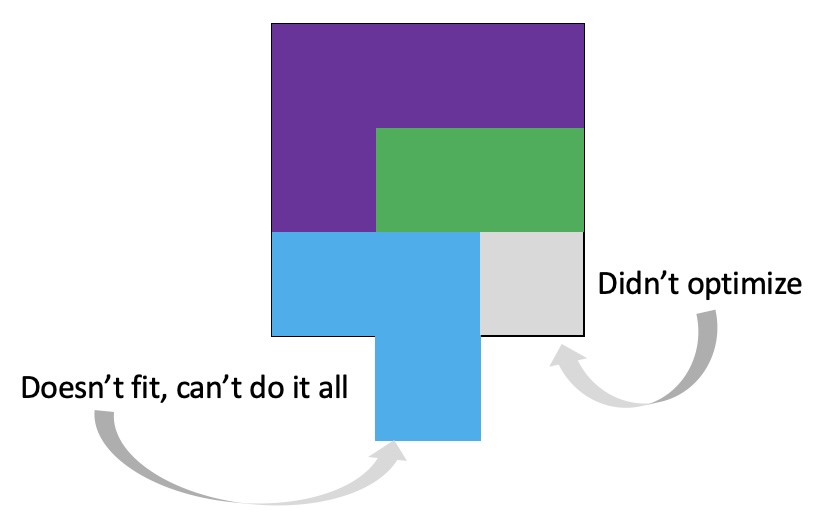

But sometimes even this feels impossible, and I’m left feeling like I can’t quite perfectly line everything up and things are getting dropped.

It’s important to remember that even if the total amount of time is “a lot”, it doesn’t have to be done all at once. Historically, a lot of us might work 8 hour days (or longer days). For those of us with desk jobs, we sometimes have options to split this up. For example, working a few hours and then taking a lunch break, or going for a walk / hitting the gym, then returning to work. Instead of a static 9-5, it may look like 8-11:30, 1:30-4:30, 8-9:30.

It’s important to remember that even if the total amount of time is “a lot”, it doesn’t have to be done all at once. Historically, a lot of us might work 8 hour days (or longer days). For those of us with desk jobs, we sometimes have options to split this up. For example, working a few hours and then taking a lunch break, or going for a walk / hitting the gym, then returning to work. Instead of a static 9-5, it may look like 8-11:30, 1:30-4:30, 8-9:30.

The same is true for other blocks of time, too, such as activities of daily living: they’re usually not all in one block of time, but often at least two (waking up and going to bed) plus sprinkled throughout the day.

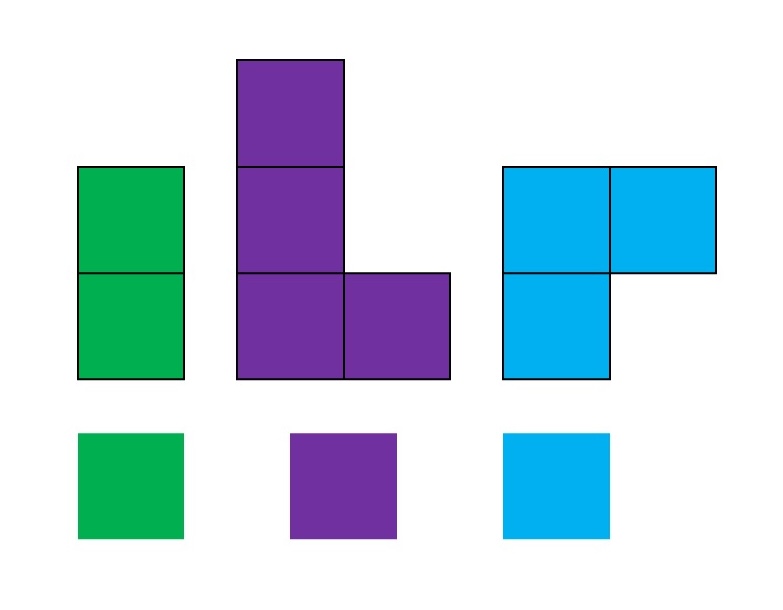

In other words, it’s helpful to recognize that these big “blocks” can be broken down into smaller subunits:

And from there… we have a lot more possibilities for how we might fit “everything” (or our biggest priorities) into a day:

For me, these new blocks are more common. Sometimes I have my most typical day with a solid block of exercise and work just how I’d prefer them (top left). Other times, I have less exercise and several work blocks in a day (top right). Other days, I don’t have energy for physical activity, activities of daily living take more energy or I have more tasks to do and I also don’t have quite as much time for longer work sections (bottom left). There’s also non-work days too where I prioritize getting as much activity as I can in a day (bottom right!). But in general, the point of this is that instead of thinking about the way we USED to do things or thinking we SHOULD do things a certain way, we should think about what needs to be done; the minimum of how it needs to be done; and think creatively about how we CAN accomplish these tasks, goals, and priorities.

A useful trigger phrase to check is if you find yourself saying “I should ______”. Stop and ask yourself: should, according to what/who? Is it actually a requirement? Is the requirement about exactly how you do it, or is it about the end state?

“I should work 8 hours a day” doesn’t mean (in all cases) that you have to do it 8 straight hours in a row, other than a lunch break.

If you find yourself should-ing, try changing the wording of your sentence, from “I should do X” to “I want to do X because Y”. It helps you figure out what you’re trying to do and why (Y), which may help you realize that there are more ways (X or Z or A) to achieve it, so “X” isn’t the requirement you thought it was.

If you find yourself overwhelmed because it feels like you have a big block task that you need to do, this is also helpful then to break it down into steps. Start small, as small as opening a document and writing what you need to do.

My recent favorite trick that is working well for me is putting the item of “start writing prompt for (project X)” on my to-do list. I don’t have to run the prompt; I don’t have to read the output then; I don’t have to do the next steps after that…but only start writing the prompt. It turns out that writing the prompt for an LLM helps me organize my thoughts in a way that it then makes the subsequent next steps easier and clearer, and I often then bridge into completing several of those follow up tasks! (More tips about starting that one small step here.)

The TL;DR: perhaps is that while we might yearn to fit everything in perfectly and optimize it all, it’s not going to always turn out like that. Our priorities change, our energy availability changes (due to health or kids’ schedules or other life priorities), and if we strive to be more flexible we will find more options to try to fit it all in.

Sometimes we can’t, but sometimes breaking things down can help us get closer.

And: patients should not be punished for asking questions in order to better understand or check their understanding.

And: patients should not be punished for asking questions in order to better understand or check their understanding.  I’ve learned from experience that waiting rarely creates better outcomes. It only delays impact.

I’ve learned from experience that waiting rarely creates better outcomes. It only delays impact. (Thank you).

(Thank you). I encourage you to think about scaling yourself and identifying a task or series of tasks where you can get in the habit of leveraging these tools to do so. Like most things, the first time or two might take a little more time. But once you figure out what tasks or projects are suited for this, the time savings escalate. Just like learning how to use any new software, tool, or approach. A little bit of invested time up front will likely save you a lot of time in the future.

I encourage you to think about scaling yourself and identifying a task or series of tasks where you can get in the habit of leveraging these tools to do so. Like most things, the first time or two might take a little more time. But once you figure out what tasks or projects are suited for this, the time savings escalate. Just like learning how to use any new software, tool, or approach. A little bit of invested time up front will likely save you a lot of time in the future.

Recent Comments