Today my inbox was suddenly flooded with links to a video with some commentary about artificial pancreas technology at a conference by a representative of the U.S. FDA. The implication many people are getting after watching the video clip is that this FDA representative is implying that people are being unsafe by building their own artificial pancreas. He mentions it is consumer prerogative to build an artificial pancreas – which is correct. The implication of his analogy is that changing your car and killing yourself is similar to a DIY artificial pancreas effort.

The scary takeaway from the video, in my opinion, as well as other public comments in the past, is the implication that the FDA cares more about the potential harms of taking action than the almost certain harms of inaction. And it’s increasingly frustrating that the FDA appears to imply publicly that those of us in the #wearenotwaiting community are doing things unsafely as a result of taking action.

Safety is what drives the #wearenotwaiting movement. In my case, I refuse to sleep another night with the fear that I won’t wake up in the morning because there’s not an FDA-approved system on the market that will wake me up if my life is in danger, let alone a system that can take action and change the situation to be more safe. So I built my own (#DIYPS), because the current FDA-approved CGM devices were not (and still are not) loud enough to wake me up at night, putting me at risk of dying in my sleep. And yes, it ultimately turned into an artificial pancreas – with the same goal of ensuring I wake up every morning, safely (alive). That is my prerogative for sure.

But I fail to see why the FDA, which collectively has no particular knowledge of these systems (especially as they have no jurisdiction, acknowledged on all fronts, over what I do myself – it’s my prerogative), is making public statements implying that these types of systems are categorically unsafe.

As a matter of fact, every DIY system I’ve seen is safer than the FDA-approved standard of care available for people with diabetes. The thousands of people using Nightscout, which is currently a DIY remote view-only monitoring system? Provides more safety and security for people with diabetes, not to mention it is helping achieve better outcomes for people with diabetes than they were able to achieve before with the standard of diabetes care as it exists today. (This was originally for the most part because of restricted access to data, although while that has improved there’s still interoperability issues getting access to real-time data in the same place from the 3+ average devices a person with diabetes uses…unless they have Nightscout or another DIY tool running.) The dozens of people working on their DIY version of an artificial pancreas system (many of whom are collaborating and sharing data in the #OpenAPS community)? These systems are safer than the standard of care, which is to let an insulin pump continue to overdose you if you are dangerously low while you sleep.

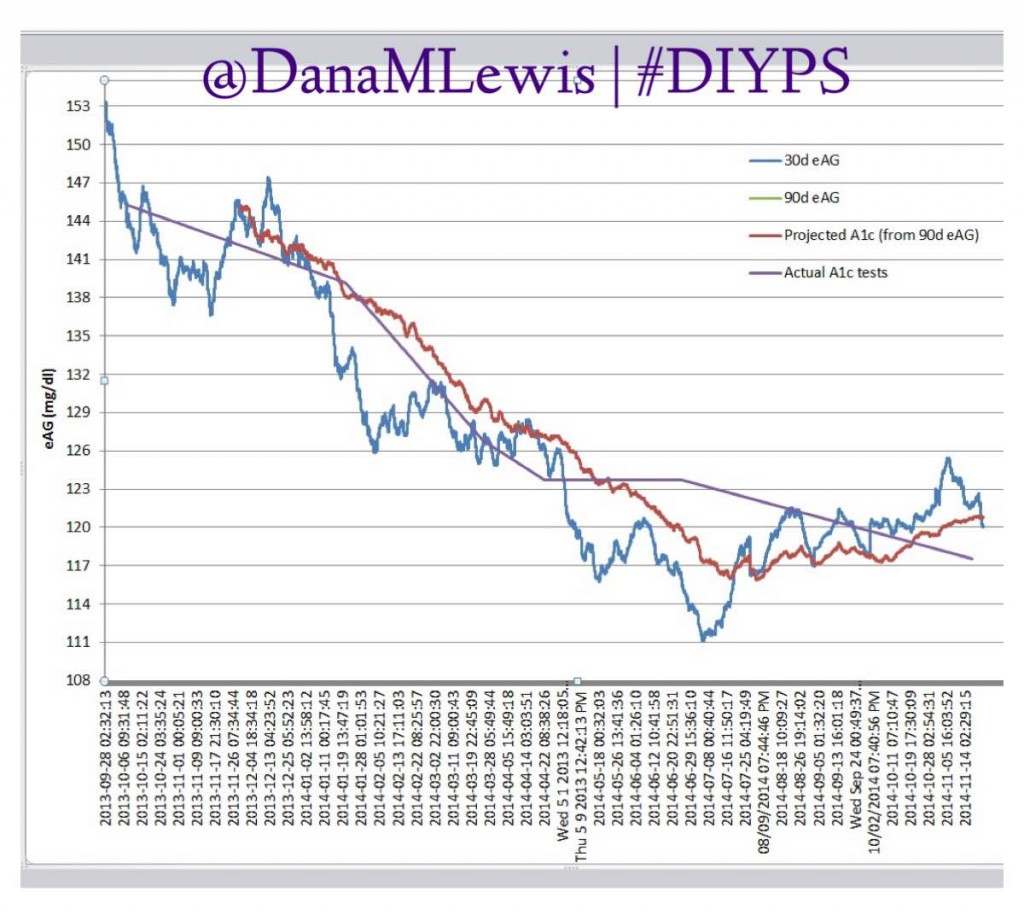

(You can see some of my personal data from #DIYPS, before we closed the loop, here and more about outcomes after we closed the loop and had #OpenAPS here. My closed loop artificial pancreas system continues to work excellently nine plus months in, and you can continue to watch my outcomes as I post them to Twitter regularly using the #DIYPS and #OpenAPS hashtags. I’ve also shared the other powerful lessons that DIY tech has helped me learn about diabetes care that helps all people with diabetes, regardless of technology.)

Are there risks to DIY efforts? Yes. But there’s risks to living with diabetes regardless. And as a person with diabetes, I am well aware of the risks that I choose to take. Diabetes is a disease in which you carry around large amounts of a lethal drug in your pocket that you are supposed to inject daily in order to save your life. As a person with diabetes, we are nothing but aware of the multitude of risks of living with this chronic disease 24/7/365.

In fact, even without a DIY artificial pancreas system, I am at risk every day simply from using my FDA-approved insulin pump that does not accurately track how much insulin I am given. (Read more here about how most insulin pumps on the market calculate IOB only from boluses, and often do not provide a record let alone incorporate any temporary adjustments to your basal rates and do not in any case track the impact of suspending your pump completely.)

And as someone who has founded the #OpenAPS movement, with the goal of an open and transparent effort to make safe and effective basic Artificial Pancreas System (APS) technology widely available to more quickly improve and save as many lives as possible and reduce the burden of type 1 diabetes…..we approach it with safety first in mind, and is a big part of why the DIY part is critical and is a part of our number one priority of safety.

Not everyone will choose to go the DIY route. In fact, most people do not and I am told all the time “Oh, I would never do that.” And that’s fine! Everyone can choose what they want for themselves.

But technology has made it increasingly feasible for those of us who want to improve our own safety to do so, because the industry and the FDA are not moving quickly enough to meet our needs.

That, indeed, is our prerogative – to increase our own safety.

Recent Comments