Academic and medical literature often is like the game of “telephone”. You can find something commonly cited throughout the literature, but if you dig deep, you can watch the key points change throughout the literature going from a solid, evidence-backed statement to a weaker, more vague statement that is not factually correct but is widely propagated as “fact” as people cite and re-cite the new incorrect statements.

The most obvious one I have seen, after reading hundreds of papers on exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (known as EPI or PEI), is that “chronic pancreatitis is the most common cause of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency”. It’s stated here (“Although chronic pancreatitis is the most common cause of EPI“) and here (“The most frequent causes [of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency] are chronic pancreatitis in adults“) and here (“Besides cystic fibrosis and chronic pancreatitis, the most common etiologies of EPI“) and here (“Numerous conditions account for the etiology of EPI, with the most common being diseases of the pancreatic parenchyma including chronic pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, and a history of extensive necrotizing acute pancreatitis“) and… you get the picture. I find this statement all over the place.

But guess what? This is not true.

First off, no one has done a study on the overall population of EPI and the breakdown of the most common co-conditions.

Secondly, I did research for my latest article on exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in Type 1 diabetes and Type 2 diabetes and was looking to contextualize the size of the populations. For example, I know overall that diabetes has a ~10% population prevalence, and this review found that there is a median prevalence of EPI of 33% in T1D and 29% in T2D. To put that in absolute numbers, this means that out of 100 people, it’s likely that 3 people have both diabetes and EPI.

How does this compare to the other “most common” causes of EPI?

First, let’s look at the prevalence of EPI in these other conditions:

- In people with cystic fibrosis, 80-90% of people are estimated to also have EPI

- In people with chronic pancreatitis, anywhere from 30-90% of people are estimated to also have EPI

- In people with pancreatic cancer, anywhere from 20-60% of people are estimated to also have EPI

Now let’s look at how common these conditions are in the general population:

- People with cystic fibrosis are estimated to be 0.04% of the general population.

- This is 4 in every 10,000 people

- People with chronic pancreatitis combined with all other types of pancreatitis are also estimated to be 0.04% of the general population, so another 4 out of 10,000.

- People with pancreatic cancer are estimated to be 0.005% of the general population, or 1 in 20,000.

What happens if you add all of these up: cystic fibrosis, 0.04%, plus all types of pancreatitis, 0.04%, and pancreatic cancer, 0.005%? You get 0.085%, which is less than 1 in 1000 people.

This is quite a bit less than the 10% prevalence of diabetes (1 in 10 people!), or even the 3 in 100 people (3%) with both diabetes and EPI.

Let’s also look at the estimates for EPI prevalence in the general population:

- General population prevalence of EPI is estimated to be 10-20%, and if we use 10%, that means that 1 in 10 people may have EPI.

Here’s a visual to illustrate the relative size of the populations of people with cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis (visualized as all types of pancreatitis), and pancreatic cancer, relative to the sizes of the general population and the relative amount of people estimated to have EPI:

What you should take away from this:

- Yes, EPI is common within conditions such as cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis (and other forms of pancreatitis), and pancreatic cancer

- However, these conditions are not common: even combined, they add up to less than 1 in 1000!

- Therefore, it is incorrect to conclude that any of these conditions, individually or even combined, are the most common causes of EPI.

You could say, as I do in this paper, that EPI is likely more common in people with diabetes than all of these conditions combined. You’ll notice that I don’t go so far as to say it’s the MOST common, because I haven’t seen studies to support such a statement, and as I started the post by pointing out, no one has done studies looking at huge populations of EPI and the breakdown of co-conditions at a population level; instead, studies tend to focus on the population of a co-condition and prevalence of EPI within, which is a very different thing than that co-condition’s EPI population as a percentage of the overall population of people with EPI. However, there are some great studies (and I have another systematic review accepted and forthcoming on this topic!) that support the overall prevalence estimates in the general population being in the ballpark of 10+%, so there might be other ‘more common’ causes of EPI that we are currently unaware of, or it may be that most cases of EPI are uncorrelated with any particular co-condition.

—

(Need a citation? This logic is found in the introduction paragraph of a systematic review found here, of which the DOI is 10.1089/dia.2023.0157. You can also access a full author copy of it and my other papers here.)

—

You can also contribute to a research study and help us learn more about EPI/PEI – take this anonymous survey to share your experiences with EPI-related symptoms!

—

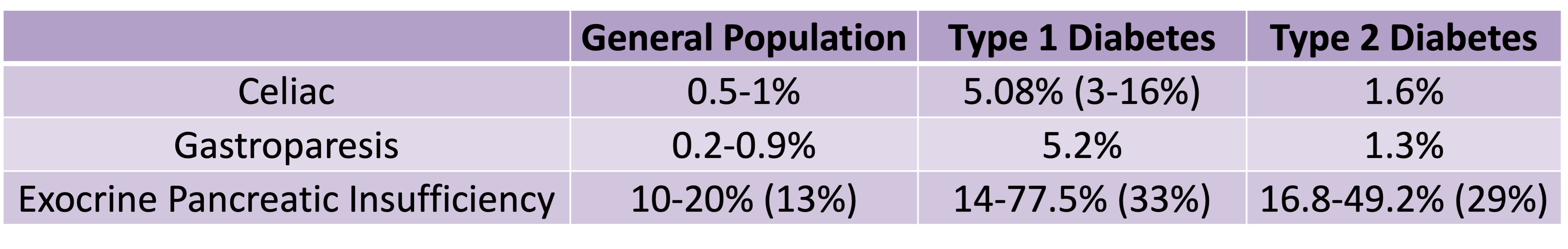

Celiac disease is more common in people with diabetes (~5%) than in the general public (0.5-1%). Gastroparesis, when gastric emptying is delayed, is also more common in people with diabetes (5% in PWD).However, the prevalence of EPI is 14-77.5% (median 33%) in Type 1 diabetes and 16.8-49.2% (median 29%) in Type 2 diabetes (and 5.4-77% prevalence when type of diabetes was not specified). This again is higher than general population prevalence of EPI.

Celiac disease is more common in people with diabetes (~5%) than in the general public (0.5-1%). Gastroparesis, when gastric emptying is delayed, is also more common in people with diabetes (5% in PWD).However, the prevalence of EPI is 14-77.5% (median 33%) in Type 1 diabetes and 16.8-49.2% (median 29%) in Type 2 diabetes (and 5.4-77% prevalence when type of diabetes was not specified). This again is higher than general population prevalence of EPI.

Recent Comments