When I was invited to contribute to a debate on AID at #ADA2023 (read my debate recap here), I decided to also submit an abstract related to some of my recent work in researching and understanding the prevalence and treatment of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (known as EPI or PEI or PI) in people with diabetes.

I have a personal interest in this topic, for those who aren’t aware – I was diagnosed with EPI last year (read more about my experience here) and now take pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) pills with everything that I eat.

I was surprised that it took personal advocacy to get a diagnosis, and despite having 2+ known risk factors for EPI (diabetes, celiac disease), that when I presented to a gastroenterologist with GI symptoms, EPI never came up as a possibility. I looked deeper into the research to try to understand what the correlation was in diabetes and EPI and perhaps understand why awareness is low compared to gastroparesis and celiac.

Here’s what I found, and what my poster (and a forthcoming full publication in a peer-reviewed journal!) is about (you can view my poster as a PDF here):

1304-P at #ADA2023, “Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI / PEI) Likely Overlooked in Diabetes as Common Cause of Gastrointestinal-Related Symptoms”

Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency (EPI / PEI / PI) occurs when the pancreas no longer makes enough enzymes to support digestion, and is treated with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT). Awareness among diabetes care providers of EPI does not seem to match the likely rates of prevalence and contributes to underscreening, underdiagnosis, and undertreatment of EPI among people with diabetes.

Methods:

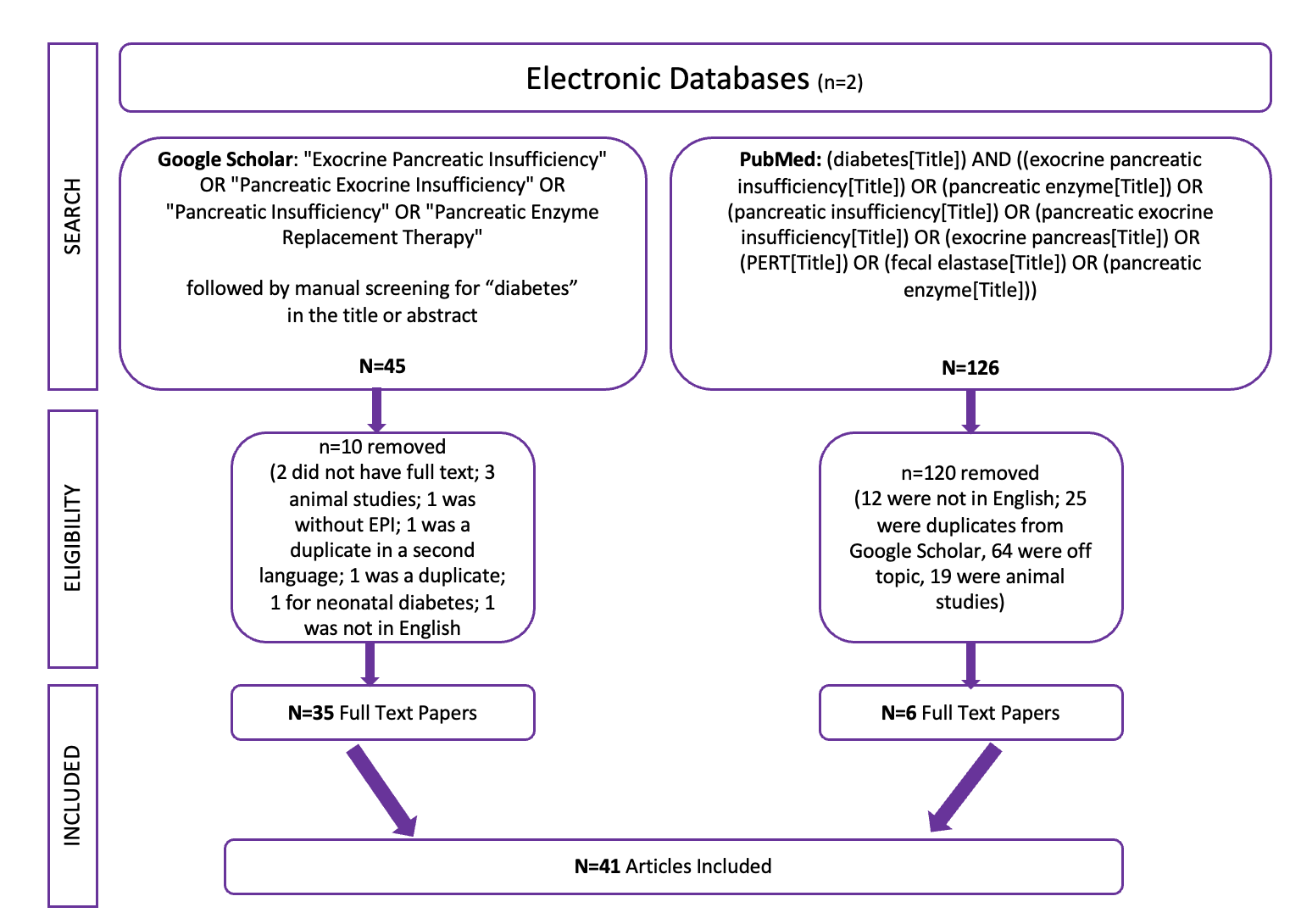

I performed a broader systematic review on EPI, classifying all articles based on co-condition. I then did a second specific diabetes-specific EPI search, and de-duplicated and combined the results. (See PRISMA figure).

I ended up with 41 articles specifically about EPI and diabetes, and screened them for diabetes type, prevalence rates (by type of diabetes, if it was segmented), and whether there were any analyses related to glycemic outcomes. I also performed an additional literature review on gastrointestinal conditions in diabetes.

Results:

From the broader systematic review on EPI in general, I found 9.6% of the articles on specific co-conditions to be about diabetes. Most of the articles on diabetes and EPI are simply about prevalence and/or diagnostic methods. Very few (4/41) specified any glycemic metrics or outcomes for people with diabetes and EPI. Only one recent paper (disclosure – I’m a co-author, and you can see the full paper here) evaluated glycemic variability and glycemic outcomes before and after PERT using CGM.

There is a LOT of work to be done in the future to do studies with properly recording type of diabetes; using CGM and modern insulin delivery therapies; and evaluating glycemic outcomes and variabilities to actually understand the impact of PERT on glucose levels in people with diabetes.

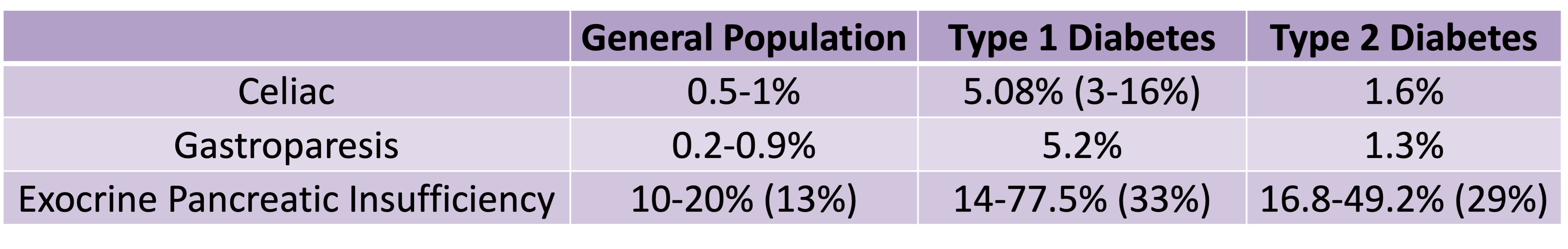

In terms of other gastrointestinal conditions, healthcare providers typically perceive the prevalence of celiac disease and gastroparesis to be high in people with diabetes. Reviewing the data, I found that celiac has around ~5% prevalence (range 3-16%) in people with type 1 diabetes and ~1.6% prevalence in Type 2 diabetes, in contrast to the general population prevalence of 0.5-1%. For gastroparesis, the rates in Type 1 diabetes were around ~5% and in Type 2 diabetes around 1.3%, in contrast to the general population prevalence of 0.2-0.9%.

Speaking of contrasts, let’s compare this to the prevalence of EPI in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes.

- The prevalence of EPI in Type 1 diabetes in the studies I reviewed had a median of 33% (range 14-77.5%).

- The prevalence of EPI in Type 2 diabetes in the studies I reviewed had a median of 29% (16.8-49.2%).

You can see this relative prevalence difference in this chart I used on my poster:

Key Findings and Takeaways:

Gastroparesis and celiac are often top of mind for diabetes care providers, yet EPI may be up to 10 times more common among people with diabetes! EPI is likely significantly underdiagnosed in people with diabetes.

Healthcare providers who see people with diabetes should increase the screening of fecal elastase (FE-1/FEL-1) for people with diabetes who mention gastrointestinal symptoms.

With FE-1 testing, results <=200 μg/g are indicative of EPI and people with diabetes should be prescribed PERT. The quality-of-life burden and long-term clinical implications of undiagnosed EPI are significant enough, and the risks are low enough (aside from cost) that PERT should be initiated more frequently for people with diabetes who present with EPI-related symptoms.

EPI symptoms aren’t just diarrhea and/or weight loss: they can include painful bloating, excessive gas, changed stools (“messy”, “oily”, “sticking to the toilet bowl”), or increased bowel movements. People with diabetes may subconsciously adjust their food choices in response to symptoms for years prior to diagnosis.

Many people with diabetes and existing EPI diagnoses may be undertreated, even years after diagnosis. Diabetes providers should periodically discuss PERT dosing and encourage self-adjustment of dosing (similar to insulin, matching food intake) for people with diabetes and EPI who have ongoing GI symptoms. This also means aiding in updating prescriptions as needed. (PERT has been studied and found to be safe and effective for people with diabetes.)

Non-optimal PERT dosing may result in seemingly unpredictable post-meal glucose outcomes. Non-optimal postprandial glycemic excursions may be a ‘symptom’ of EPI because poor digestion of fat/protein may mean carbs are digested more quickly even in a ’mixed meal’ and result in larger post-meal glucose spikes.

—

As I mentioned, I have a full publication with this systematic review undergoing peer review and I’ll share it once it’s published. In the meantime, if you’re looking for more personal experiences about living with EPI, check out DIYPS.org/EPI, and also for people with EPI looking to improve their dosing with pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy – you may want to check out PERT Pilot (a free iOS app to record enzyme dosing, now also available for Android).

Researchers, if you’re interested in collaborating on studies in EPI (in diabetes, or more broadly on EPI), please reach out! My email is Dana@OpenAPS.org