Confession: I like to plan things. However, there’s one thing I can’t (won’t/wouldn’t) plan, which was our engagement.

Some time ago, I had joked that if/when we got to the point of making this decision, that he definitely couldn’t do it while I was low, because I would be feeling awful and I wouldn’t necessarily be able to remember every detail, etc.

Fast forward to this weekend

Scott and I hopped in a van on Thursday and drove down to Portland to get ready for Hood to Coast. Luckily, unlike my Ragnar run, our start time was a more civilized 9:30 am so we had time to see the sunrise before we started the race on Friday.

We headed up the mountain, and then I kicked off the race by running down the mountain (awesome). We then proceeded with the race, which like Ragnar, is completed by having 12 runners in 2 vans take turns covering the course until ultimately you end up in Seaside, Oregon to finish. There were some snafus on the course by the organizers, including an hour-long-plus backup on the road where you were supposed to be able to get to a field and be able to sleep in said field. However, by the time we had arrived, they closed the field, so we ended up getting less than an hour of sleep on the side of the road, smushed together in the van (7 people in one van!), before I had to crawl outside and force another few miles for my last run.

But, we finally finished, made it to Seaside on Saturday afternoon, and stood around waiting for our van 2 to fight through traffic and get there so we could cross the finish line together and be done! Everyone from our van (including Scott) ended up standing around in a crowd with a few thousand of our closest friends for more than an hour. Once they made it, we crossed, grabbed our medals…and were done.

Most of the team decided to head into the beer garden before splitting up for dinner and heading back to the hotel. I voted for heading back to dinner right away, because the sooner I ate, the sooner I got to finally go to sleep! Scott and I decided to head back.

Where I start unintentionally thwarting Scott’s plans

Scott suggested walking on the beach as we headed back, but as we skirted the finish line area, I realized how much it hurt to walk on the uneven sand with sore legs and hips from the run, and vetoed that idea. So we walked up off the beach to the esplanade/promenade, and walked down it instead. I called my parents to let them know we were alive after the race, and by the time I was off the phone, we were nearing the end of the esplanade. Scott asked one more time if I was sure I didn’t want to walk out to the beach. I think I said something along the lines of, “Fine, we can walk up to the beach, as long as we don’t have to walk up and down it!”

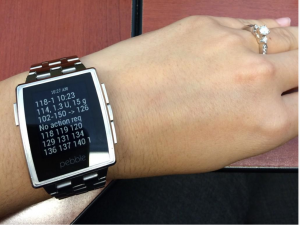

We walked over to the edge of the beach on the ridge, where you could see the fog and not much else, although there weren’t many people around. At that point, Scott was checking #DIYPS on his watch, and saw that I was dropping from the walk and projected to go low, so he suggested sitting down for a few minutes as a break before we walked the rest of the way back to the hotel for dinner, and starting a temp basal to help prevent a low. He told me to pick a spot, so I picked a comfortable looking log, and we sat down. Scott gave me a few Swedish fish to eat just to make sure I didn’t go low, and then while I was looking around at the fog, he started reaching into his pocket again and telling me he had another question for me.

I still had no idea what was going on (something about running a lot of miles and 1 hour of sleep), so I just looked at him. He pulled a box out of his pocket and opened it to another box, and I started to have an inkling of what MIGHT be happening, but my brain started to tell me that nope, wasn’t happening, what kind of person carries a ring in their bag/pocket all weekend around so many people without me noticing it, and didn’t we just run a race on one hour of sleep, and oh my gosh what is he doing?

By that point, he had flipped around and gotten down on one knee, asked me if I was ready to make it official, kissed me, and asked me to marry him. Thanks to #DIYPS I was *not* low, and despite the lack of sleep I had figured out what was going on at this point, and was able to say yes!

For those keeping track at home, despite my BGs starting to swing low which was supposed to be the reason we stopped to sit down…I later looked, and my BG never dropped below 99 during all of this!

Recent Comments